La Grande Bretèche (Another woman’s study)

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Fourth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877) Scenes from private life

LA GRANDE BRETECHE (Another study of a woman)

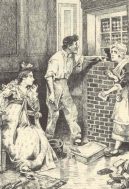

Analysis and History Study published in 1842 to provide a sufficient number of pages for Volume II of La Comédie humaine. It’s a conversation between witty people at the end of a supper. Henri de Marsay, Balzac’s most brilliant dandy, recounts his first female adventure. Conversation ensues between the guests, and it’s this witty, lively exchange, in which each brings his or her own anecdote, that allows the novelist’s back drawers to be inserted. A few fragments ofUne conversation entre onze heures et minuit published in 1832 in the collective collection of Brown Tales, then the portrait of La femme comme il faut, published in 1839 in another collective collection, The French painted by themselves, then The mistress of our colonel, who had been another of the Brown tales and The Duchess’s death, a short fragment of the same origin, finally the bravura piece, La Grande Bretèche, already in use, a montage entitled Le conseil , which Balzac later dismembered and published separately with two other tales under the title La Grande Bretèche ou les Trois vengeances, and finally in The department’s Muse. The tale of La Grande Bretèche is the last story told by Henri de Marsay to his dinner companions. The story is about a tragedy that took place in a house near Vendôme, on the banks of the river Loir. The storyteller is intrigued by this property, which has been abandoned for ten years, and regularly wanders around in search of emotions. These visits were soon forbidden by Monsieur Regnault, notary and executor of the will of the late Madame la Comtesse de Merret. This notary, in accordance with the wishes of the deceased, is the guardian of this dwelling for a period of 50 years from the death of Madame de Merret, forbidding entry to the apartments to any person whatsoever, and forbidding the carrying out of the slightest repairs – even allocating an annuity in order to pledge guardians, should the need arise, to ensure the full execution of his intentions. At the end of this term, if the testatrix’s wish has been fulfilled, the house must belong to the notary’s heirs, as notaries cannot accept bequests; otherwise, La Grande Bretèche would revert to the rightful owner, but on condition that the conditions set out in a codicil appended to the will, which must be opened only at the end of the 50 years, are fulfilled. The will has not been attacked (claimed, therefore….the notary is rubbing his hands…). Beneath these conditions lies the most terrible of secrets. Three months before the evening of the tragedy, Madame de Merret had been seriously indisposed enough for her husband to leave her home alone, and he was sleeping in a room on the second floor. By one of those unforeseeable coincidences, he returned that evening two hours later than usual from the Cercle, where he’d been reading the papers and chatting politics with the locals. His wife thought he’d gone home, gone to bed, asleep. For some time now, when he returned home, Monsieur de Merret would simply ask his wife’s maid Rosalie if Madame de Merret had gone to bed – and when she replied in the affirmative, he would immediately go home with the bonhomie born of habit and confidence. That evening, on his way home, he fancied going to Madame de Merret’s house to tell her all about his evening’s misadventures. During dinner, he had found Madame de Merret coquettishly dressed; he told himself that his wife’s convalescence had embellished her. Not seeing Rosalie, Monsieur de Merret went straight to his wife’s room. As he turned the doorknob, he thought he heard the door to the study adjoining his wife’s bedroom close. Sensing an awkwardness in his wife’s demeanor and an altered tone in her voice, Monsieur de Merret said coldly: Madame, there’s someone in your study! and went over to open the door. Joséphine dissuaded him, threatening to break up with him. Joséphine swore on the Bible that no one was in her study, and asked her husband not to open the door. Nevertheless, the suspicious husband sent for Gorenflot the bricklayer and, in the presence of Madame de Merret, had him wall up the cabinet door. When the wall was halfway up, the cunning mason took a moment when the gentleman’s back was turned to strike a blow with a pickaxe through one of the door’s two panes of glass. All three (Gorenflot, Rosalie, Joséphine) then saw a dark, brunette figure, black hair, a fiery gaze. Before her husband had turned around, the poor woman had time to nod to the Spaniard, as if to say “keep hoping”. At four o’clock, around daybreak (it was September), the wall was completed. The mason remained in Jean’s care, and Monsieur de Merret slept in his wife’s room. During one of her husband’s brief absences, Joséphine and Rosalie set about demolishing part of the wall to free their imprisoned lover. She had already knocked over a few bricks when she saw Monsieur de Merret behind her. Anticipating what would happen in his absence, he had set a trap for his wife. The scorned husband went so far as to stay locked in his wife’s room for twenty days, on the pretext of looking after his sick wife. During the first moments, when there was some noise in the walled room and Joséphine wanted to implore him for the dying stranger, he would reply, without allowing her to say a single word: “You swore on the cross that there was no one there”. Madame de Merret died of grief and guilt. Monsieur de Merret, exiled to Paris, died a few months before his wife. There he perished miserably, indulging in all manner of excesses. To forget, no doubt! Paris, June 1839 – 1842

Source analysis: Preface and story compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (Tome V) published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

Genealogy of characters Merret (de): Count of Merret. “Handsome man”, but a bad character, in Vendôme, died in 1816. His wife’s maiden name is not known. Named Joséphine, she died around 1816. Rosalie: Maid to the Merret family, near Vendôme. Gorenflot: Mason in Vendôme. Jean: Domesticated by the Merret family.

Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” – Gallimard.

No Comments