A daughter of Eve

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Second volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877) Scenes from private life

UNE FILLE D’EVE Short story published in the Siècle newspaper in January 1839

Analysis of the work

Une fille d’Eve (A Daughter of Eve ) is a long novella first serialized in the newspaper le Siècle in December 1838 and January 1839, then in two in-8° volumes, published by Hippolyte Souverain in August 1839, then in the Furne edition of 1842, where it was placed in the Scenes from the private life of The Human Comedy. Une fille d’Eve is a title that doesn’t mean much. Balzac had noted this in an album he called his “vivier”, in 1832, when he was gathering titles for a collection of “women’s studies” he was planning at the time. Then he thought no more about it. The long novella or short story that we read today under this title, published in December 1838, is too considerable to take its place among the “women’s studies”: it’s halfway between the “women’s studies” and the “women’s studies”. Scenes from Parisian life to which it belongs, through the characters it portrays and the Scenes from private life A young woman must defend herself against the temptations that admiration or enthusiasm can provoke. In fact, it is above all an example of how Balzac’s various works are related to each other after 1835, thanks to the reappearance of characters. It’s the day after a story whose beginning is told in Une double famille, a short story published in 1830. The Grandvilles, he a public prosecutor, she a pious wife, had two daughters who were brought up in the devotional principles professed by their mother: complete ignorance, forced marriage, easy and happy worldly life, but no experience, no mistrust, an unoccupied heart. An encounter moves one of these white geese. She lets her imagination run wild and dreams a little too much about a rugged, tall, ugly, powerful man who seems to her the very image of genius. Like Eugénie Grandet andAlbert Savarus‘s Rosalie de Watteville, she creates a hero and a novel for herself. Circumstances that call on her dedication and generosity put her in danger. She was saved by her husband’s skill and tenderness just as she was about to be seriously compromised. This plot takes us away from the orbit ofUne double famille, which tells the story of the youth of Attorney General Granville, but returns us to the subject ofIllusions perdues, a description of the Parisian literary milieu and the “illusions” of the provinces, the first part of which had just been published in 1837. It’s the same adventure, but on a different social level. The Comtesse de Vandenesse in a salon in the noble Faubourg Saint-Germain falls victim to the same “illusion” as Mme de Bargeton in Angoulême when she compromises herself with Lucien de Rubempré: but the one, provincial and borrowed, is seduced by a primitive image of poetry, the young prodigy from the prefecture in whom she believes she sees Lamartine, while the other, Parisian and more refined, is attached to power, to a stormy destiny, to an eagle who imposes himself on other men. Just as the first part ofIllusions perdues, which he had just written, provided Balzac with his subject, the second part ofIllusions perdues, entitled Un grand homme de province à Paris (A great man from the provinces in Paris ), which he was preparing at the time, provided him with the Parisian setting and the extras for his action. The social milieu in which the Comtesse de Vandenesse meets Raoul Nathan is obviously not the same as the literary milieu in which Lucien de Rubempré begins his career. But the extras, the utilities, the ambitions, the instruments of ambition are all the same. They are the indispensable elements of the path to success. It’s like a setting that Balzac constructs in his mind, to be used both for the short story he writes and for the novel he prepares, the enrichment of which can be seen in the considerable additions Balzac adds to the proofs of his short story. These are not the only interferences to be seen, but only the most visible. There are others. Félix de Vandenesse, the intelligent, tender husband who comes to his wife’s rescue in the novella’s denouement, is the main character in Balzac’s Le Lys dans la vallée, published in 1836. The other sister’s husband, the financier Du Tillet, one of the “wolf-cerviers” of the Comédie humaine, had made his debut in César Birotteau, published at the end of 1837. Thus, the novels and short stories Balzac had just published or was preparing, and even those he had published several years earlier, provided him with a common fund, a kind of “reservoir” from which he could draw characters, situations and means. This society, which Balzac, in his own words, “carries in his head”, is as alive and present in his invention as the environments through which he passed. But, of course, when it comes to the literary world in particular, Balzac can also draw on his memories and experience. Raoul Nathan is probably, like the poet Canalis in Modeste Mignon, a composite character. The model for his powerful ugliness has not been identified among his contemporaries. But in many ways, he resembles Balzac. His ambition to be a party leader, to deal as an equal with the Ministry, was the ambition Balzac confessed to Madame Hanska when he bought the Chronique de Paris. His candidacy for parliament evokes Balzac’s various attempts to win a seat. Nathan is ambitious to make himself worthy of his aristocratic conquest, just as de Balzac wanted to make himself equal in rank to Madame Hanska. The instrument of this ambition is a newspaper that swallows up Nathan’s capital as the Chronique de Paris had swallowed up Balzac’s. And the very details of the catastrophe, in particular the guarantee that Raoul Nathan demands from the woman he loves, is the loan that Balzac, in the same circumstances, accepted from his mistress of the day, Countess Guidoboni-Visconti. Balzac is unrecognizable under the mask of Raoul Nathan: but those who know his life cannot fail to notice these analogies. Is the same true of Marie de Vandenesse? Petite and graceful, she physically resembles the “piccola” Clara Maffei, wife of the poet Andréa Maffei, one of the queens of Milan, to whom Balzac had indiscreetly courted the previous year. Her husband had written her a very touching and charming letter to warn her against Balzac’s assiduities, which she shunned after receiving it. Was Balzac aware of this letter? Félix de Vandenesse’s kind advice, which helped him regain his wife’s love, is an echo of this Italian savoir-vivre. But it’s only a meeting. Balzac’s situation in Milan was nothing like Raoul Nathan’s in the Parisian jungle. The end of the story, a little too easy, a little too industrious, reminds us of the casualness with which Balzac sometimes disposes of his endings. It’s no better than the subterfuge that ensures the happy ending to Modeste Mignon.

The Story First, it’s the day after a story whose beginning is told in A double family The Granvilles, he (Roger) a public prosecutor, she (Angélique) a pious wife whose two daughters Marie-Angélique and Marie-Eugénie were brought up in the principles of religious devotion professed by their mother: complete ignorance, forced marriage, easy and happy worldly life, but no experience, no defiance, an unoccupied heart. A meeting with Raoul Nathan, a poet, journalist and unknown writer with political connections, moves Marie-Angélique, Countess Félix de Vandenesse. She lets her imagination run wild, dreaming a little too much about this rugged, tall, ugly, powerful man who seems to her the very image of genius. Her imagination got the better of her, and she made a hero out of Nathan, and a novel out of him. Circumstances that call on her dedication and generosity (for love of Nathan) put her in danger. She seeks financial help from her sister, Madame du Tillet (wife of the famous banker who, unbeknownst to his wife Marie-Eugénie, has sworn to Nathan’s downfall, lest he overshadow her hopes of political fortune. He will ruin Nathan who, for lack of money, will give up his share in the newspaper he has created). Countess Félix de Vandenesse was saved by her husband’s skill and tenderness just as she was about to be seriously compromised. Aux Jardies, December 1833

Source analysis: Preface* and summary of the story: tome IV, based on the complete works of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac. *Thepreface is enriched in the first paragraph with additional notes from the Wikipedia universal encyclopedia.

Genealogy of characters Vandenesse (de) : Noble family from Touraine, represented by a Marquis de Vandenesse, who died around 1827. Married a Listomère from which : Charles, comte then marquis, diplomat born in 1790, married Emilie de Fontaine, widow of Kergarouët, from whom at least one son, Alfred, was born; Charles was also the father of Mme d’Aiglemont’s last four children; Félix, viscount then count, born in 1794, married Marie-Angélique de Granville born in 1808, from whom : A daughter who marries Listomère, Another girl. We should also mention an Abbé de Vandenesse, a great uncle of the above. Granville: Marie-Angélique wife of Félix de Vandenesse, daughter of Roger Granville (see Une Double famille). Nathan: (Raoul) Writer and journalist, married Sophie Grignoult, known as Florine. Tillet (du): Ferdinand (dit du), foundling, then clerk, banker, member of parliament, born 1793. Married in 1831, Marie-Eugénie de Granville born in 1814.

Source genealogy of characters: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

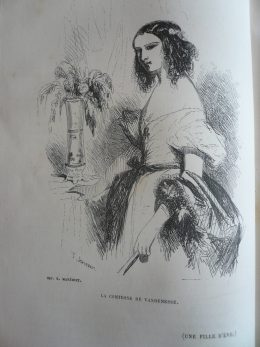

The Countess of Vandenesse

No Comments