Father Goriot

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Ninth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Father Goriot at the Pension Vauquer

LE PERE GORIOT Analysis of the work Le Père Goriot was first published in the December 1834 and January 1835 issues of the Revue de Paris, and immediately thereafter in bookshops, without being classified in any of the major divisions of Balzac’s work. In a scrapbook kept by Balzac, amid notes relating to the year 1834, we find this indication: “Subject of Père Goriot. A good man; bourgeois pension; 600 francs annuity; having stripped himself for his daughters, who both have 50,000 francs annuity, dying like a dog.” The event that served as a model, says Balzac, a few years later, “offered horrifying circumstances, the likes of which cannot be found among Cannibals; the poor father cried out for 24 hours of agony for a drink, with no one coming to his aid – his two daughters were one at the ball, the other at the show, although they were not unaware of their father’s condition”. On October 18, 1834, Balzac announced to Madame Hanska the new work he intended to draw from it: “The painting of a feeling so great that nothing exhausts it, neither friction, nor wounds, nor injustice; a man who is a father, like a saint, a martyr is a Christian. ” This is the starting point of the work. At first, Balzac wanted to make a novel. He thought he could write it in a few days. But soon, in the course of the work, the novel’s proportions and meaning change. Balzac sent a letter to his printer Everat, pointing out that Le Père Goriot will not be a “short story” as originally planned, but a much longer work. To Madame Hanska, on December 28 1834, Balzac gives a description of his novel that completes his first definition: ” Le Père Goriot is a beautiful work, but monstrously sad. It was necessary, to be complete, to show a moral sewer of Paris, and it has the effect of a disgusting sore.” A few days later, Balzac observed: “It’s above all my previous compositions… Eugénie Grandet, l’Absolu everything is surpassed…the most bitter enemies have bent the knee, I have triumphed over everything, friends and envious alike.” The idea Balzac wants to express in his work is the ruthlessness of the pressure exerted by money in a society that is only interested in satisfying vanity at the expense of natural feelings. The drama he wants to show is one of the typical dramas that occur then, when a violent, exclusive passion is crushed by this ruthless pressure. The moral he draws from this is that the system degrades people’s consciences, inviting the most skilful to prefer the short routes to fortune by unscrupulous means. The result is a novel in which money and worldly vanity are the mainsprings of action: and, at the same time, a symbolic drama whose characters are the victim, the old Goriot, the cynic, the rebellious Vautrin, the witness Rastignac. This drama is seen through the eyes of Rastignac, who has come from the provinces to study law, and discovers the world as it is: it is therefore also the story of an initiation. The “moral sewer of Paris” isn’t this miserable pension Vauquer, a cavern unknown to walkers, where retired people, students and cheerful companions whose resources are enigmatic, but rather these brilliant existences, each with its own secret wound. The most luxurious private lives are also impenetrable lairs. Paris is a theater on which unknown tragedies are played out every day. The closed circles where fortunes are made are difficult to access. Rastignac’s good fortune is to belong to a provincial family whose name opens doors. This is the beginning of his initiation. The first pages of the novel, the hustle and bustle of the Pension Vauquer, the smell of boarding houses, the piteous sparteries, the jokes at the table d’hôte, this extraordinary burrow full of swarms and effluvia, is just a prelude. The action begins when Rastignac takes a carriage to present cards to the Countess de Restaud and her relative, the Viscountess de Beauséant. He realizes that not only is it hard to be part of this exclusive, glittering society, it’s also hard to stay there. Everything is a trap and everything is a performance. To participate in this community requires a facade of wealth and elegance that his family cannot provide. Then, under the linden trees of the Pension Vauquer, the great scene takes place in which Vautrin explains to Rastignac the rules of the game for making a fortune. After showing him the dead end of his law studies, Vautrin brutally begins his profession of faith: “A rapid fortune is the problem that fifty thousand young people, all in your position, are currently trying to solve. You are just one of them… Do you know how we make our way here? By the brilliance of genius, or by the skill of corruption… Work, understood as you understand it at the moment, gives, in old age, an apartment at maman Vauquer’s to guys of Poiret’s strength… Honesty is useless. “And he goes on to apply these principles. “If you want to be rich quickly, you have to be rich already, or appear to be. To get rich, you have to make big moves, otherwise you carrot… Draw your own conclusions. That’s life as it is. It’s no nicer than cooking, it stinks just as much and you have to get your hands dirty if you want to make a living; just know how to wash up properly: that’s the moral of our age. ” As for the means, they vary, depending on the circumstances: “Paris, you see, is like a forest in the New World, where twenty species of savage tribes, the Illinois, the Hurons, live off the proceeds of the various social hunts: you are a hunter of millions. “He enumerates: “Some hunt for dowries, others hunt for liquidations, these fish for consciences… Whoever comes back with a well-stocked bag is greeted, feted, received into good society. “And, naturally, for Rastignac, it’s dowry hunting that Vautrin offers. He points out a sweet, chlorotic orphan girl who lives near him, at the Vauquer boarding house, and whose duel can turn her into a wealthy heiress overnight. Rastignac, appalled, looks for another way: and he finds it. Despite his refusal, he was disturbed by Vautrin’s cynicism. For this cynicism was in line with another lesson she’d been taught earlier by the Viscountess de Beauséant. He had found her in a moment of despair. The man to whom she had devoted her entire life had left her. In her grief, she had been as frank as Vautrin was cynical. The world is vile and wicked,” she told him. Well, Monsieur de Rastignac, treat the world as it deserves. You want to succeed, I’ll help you. The more coldly you calculate, the further you’ll go. Accept men and women only as post-horses that you’ll let die at every relay… You see, you’ll be nothing here if you don’t have a woman who’s interested in you. You need her to be young, pretty, elegant… In Paris, success is everything; it’s the key to power. If women find you witty and talented, men will believe it… Then you can have your cake and eat it too. Then you’ll know what the world is, a meeting of dupes and rascals. ” It was, in another mode, the same speech as Vautrin’s. And it ended with the same proposal. The Vicomtesse de Beauséant threw one of Goriot’s daughters, Mme de Nucingen, wife of an ambitious banker, into Rastignac’s arms. The drama then unfolds in two series of scenes that illustrate these warnings. “Fortune at any price!” cries Rastignac, “gold and love aplenty. ” But since Vautrin has ignored Rastignac’s refusal, he prepares the duel he has planned. Rastignac is invited by Madame de Nucingen: he’s elegant, he’s transformed, but he’s frightened by the expenses he’s obliged to incur, he hesitates. Fate decides. Vautrin’s arrest determines Rastignac’s future. Vautrin’s ferocity and audacity are on full display in the prodigious scene of verve and color in which he intoxicates Mme Vauquer’s boarders with his bottles of old claret mixed with narcotic. Vautrin’s cheerfulness, his truculence, and then, the next day, his composure and self-control at the moment of his arrest, give extraordinary power and reality to this character from a novel noir. The scene ends with Mme Vauquer’s homeric complaints about the disasters befalling her boarding house. It’s over with Vautrin. And Goriot, victorious, inaugurates with Rastignac the charming bachelor apartment Delphine has furnished for their love. Immediately afterwards, the reader is right in the middle of the drama. Suddenly, the old Goriot learns of the tragedy of his two daughters, Mme de Nucingen ruined by her husband who has engaged her dowry in speculation, Mme de Restaud confessing that she has paid her lover’s debts, that she has sold jewels that did not belong to her, that her husband knows everything, that she too is ruined and has ruined her children. This wild scene is one of the most beautiful and poignant of Balzac’s works. Old Goriot’s cries as he watches his lifelong dream crumble, his desires for revenge, the accusations he makes against himself in his despair, the jealousy and hatred of the two sisters who insult each other in front of him, and suddenly Goriot, stunned by this double catastrophe, screaming, finally collapsing, shattered by his impotence, by this avalanche of millions to be found in a few hours, struck down by a congestion of rage and despair in this sinister room where two women sobbing beside him, whom everyone believes to be rich, happy and envied, is a striking image of those storms born of the furious clash of passions against the impassable dikes that laws and the world erect before them. The novel ends after this great scene of the double defeat of those who believed in something. Mme de Beauséant was a magnet for the whole of Paris; people flocked to her home on the day the marriage contract of the man for whom she had sacrificed everything was signed in the presence of the king. Goriot appeared for the last time at the pension’s table d’hôte, dazed and trembling, and the fatal congestion set in over the next few days. Then begins her agony, her cries, her calls, her waiting for her daughters, in that gloomy boarding house where everyone else has left. In this rout, everything is sinister. The valet de chambre wanders about in dismay, Mme Vauquer and her maids moan and worry, not about the death but about the destitution of their lodger, Rastignac puts his watch in the Mont-de-Piété, he and his friend Bianchon surround old Goriot with enormous sinapisms, and they have no money left for the last expenses or even for a simple tip : Goriot, suddenly a Shakespearean character, sees the cruelty of men and the impotence of laws, he sees his defeat without remedy, and, in this agony, he discovers, he suddenly sees what he had never wanted to see, the ingratitude and selfishness of his two daughters. At his last moment, the illusion that had been his whole life charitably comes to his rescue, and he dies, soothed, stroking Rastignac’s hair, which he has mistaken for the hair of his daughter, called in vain. The coffin on two trestles on the sidewalk of the boarding house, the poor man’s hearse, the freezing mass, and, at the cemetery, the two empty, symbolic, armorial carriages that show up to follow the convoy, end the novel on a nightmarish grayness. The last, famous image is that of Rastignac, standing at the top of Père-Lachaise, contemplating the “beaux quartiers” stretching from Place Vendôme to Les Invalides, and shouting at them in rage: “Now it’s just the two of us. ” Is Rastignac the ambitious man he has become? After Le Père Goriot perhaps, but in Le Père Goriot? What’s nice about him is that he doesn’t behave like an ambitious man. He’s young (he’s 21), confident, generous, instinctive: the exact opposite of a calculator. “Me and life,” he says, “we’re like a young man and his bride.” And it’s true. His affection for Père Goriot is spontaneous. It’s not a calculation. His indignation at Mme de Beauséant is a naive impulse of the heart, his love for Delphine de Nucingen is not a lie, he is sincerely happy to be loved. He’s sympathetic precisely because he’s not on the side of the clever, he’s on the side of the victims. It’s Father Goriot’s death that makes him change sides, and he then, but only then, becomes another Rastignac. Rastignac serves to guide the reader, but he’s not the main character. Neither did Vautrin. His build, his strength, his very physiognomy, he is, physically, the actor Frédérik Lemaître when he played Robert Macaire in L’Auberge des Adrets, but transposed into the regime of violence. In Le Père Goriot, Vautrin is still in the early stages of his career, and Balzac is just introducing him. The main character is indeed the one indicated by the title, Father Goriot. It is indeed, as Balzac predicted, “a man who is a father like a saint a martyr. is Christian”. For him, fatherhood is predestination. He has a peculiarity of the great imaginative: he lives off the happiness of his daughters, their happiness or sorrow reverberating through him, taking the place of his life. “I live twice,” he tells Rastignac. “He loves Rastignac,” Balzac would later say, “because his daughter loves him.” It’s both a delegation and an appropriation of happiness. A true sentiment, Balzac adds, and more common than you’d think. “Let everyone look around and want to be frank,” he says, “how many Father Goriots in petticoats wouldn’t we see? ” Father Goriot’s human truth is the truth of the passions, and has nothing to do with propriety or morality. These exclusive, absolute feelings have a savage brutality. Goriot is awkward,” said André Bellessort, “when he talks about his daughters with the effusions and outbursts of a lover. In Balzac’s words, “the good man is in revolt against social laws out of ignorance and sentiment, just as Vautrin is in revolt out of his unrecognized power and the instinct of his character”. He too is a savage, “an Illinois, a Huron from the Halle au Blé”: a savage, because all passion transforms like this.

The Story The point is to explain a father’s exclusive and absolute passion for his daughters. The indigence and gradual decline of this man, who ruins himself and becomes the slave of his daughters, who disown and are ashamed of him. Eugène de Rastignac is the son of a renowned provincial family. Related to Madame la vicomtesse de Beauséant through the Marcillacs, and supported by her, he found himself open to the best hotels and the greatest fortunes. Dazzled by the splendors of the world, Eugène abandoned his studies to conquer the nobility, and it was to Madame de Nucingen that he first set his sights, before turning to her sister Madame de Restaud. Vautrin, whom he rubs shoulders with at the Pension Vauquer, explains to him that honesty is useless, and that to obtain fortune quickly, one must be rich or appear to be rich, and be a million-dollar hunter: some hunt for dowries, others for liquidations, and so on. It’s the hunt for the dowry that Vautrin proposes to Rastignac when he points out Victorine Taillefer, the chlorotic young boarder at the Pension Vauquer. Victorine, disinherited in favor of her brother, would be heir to the family fortune if he were to die. Vautrin understands this, and it’s dowry hunting that he proposes to Rastignac. The plot is as follows: Vautrin arranges for one of his henchmen to kill Victorine’s brother in a duel. This service, which Vautrin estimates at 200,000 francs payable after Rastignac’s marriage to the wealthy heiress, appalls Eugène, who seeks another path by becoming Mme de Restaud’s lover. Fortune at any price,” cries Rastignac, “gold and love aplenty! But since Vautrin has ignored Eugène’s refusal, he prepares for his premeditated duel. Rastignac is invited by Mme de Nucingen: he’s elegant, he’s transformed. However, he is frightened by the expenses he has to face, and hesitates (he has asked his mother and sisters for a substantial financial advance). Fate decides. Vautrin’s arrest determines Rastignac’s future. Having bled for his two daughters, Old Goriot suddenly learns of their tragedy. Mme de Nucingen has been ruined by her husband, who has invested her dowry in risky speculation. Mme de Restaud confesses that she has paid her lover’s (Count Maxime de Traille) debts by selling the jewels belonging to her husband’s family – that she too is ruined and has ruined her children. This wild scene is one of the most beautiful and poignant of Balzac’s works. Old Goriot’s cries and pain as he watches his lifelong dream crumble, his desire for revenge, his accusations and self-reproach in despair: (for him, this tragedy is the result of the lax, passionate upbringing of his spoiled children). The jealousy and hatred of the two sisters who insult each other in front of him. This hatred stems in part from the social difference between the bourgeoisie and the nobility at the time. The nobility doesn’t mix with or entertain the bourgeoisie. Delphine’s refusal to let her sister in closes off all the salons where wit and fortune shine. Anastasie will never forgive her sister for this insult. Goriot, overwhelmed by pain and powerless to cope with this avalanche of millions to be found in just a few hours, is struck down by a stroke. It’s in this sinister, cold room, devoid of everything, where his two darling daughters, whom everyone believes to be rich, happy and envied, are sobbing, that the poor father will die. It’s a striking image of those storms born of the furious clash of passions against the impassable dikes that laws and the world erect before them. The novel ends with the terrible death of Father Goriot, who hopes in vain for a visit from his daughters until his last breath. Only Rastignac and Bianchon, a medical student and boarder at the Maison Vauquer, will care for and assist the poor father in his agony. Despite their pleas and prayers to Anastasie and Delphine for their father to have a burial worthy of him, no money will be forthcoming, and it’s Rastignac and his friend the doctor who will devote themselves and contribute, as a last tribute to the old man, to offer him the hearse and the poor man’s mass. At the cemetery, the two armorial carriages, symbolic but empty of their occupants, follow the convoy – only Bianchon and Rastignac, disgusted by such indifference and dryness of heart, sincerely accompany the deceased to his final resting place. The last, famous image is that of Rastignac contemplating, from the top of Père-Lachaise, “les beaux quartiers” stretching from the Place Vendôme to the Invalides, and hurling at them his cry of rage, “A NOUS DEUX MAINTENANT!”

Source analysis: Preface and story compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (Tome VI) published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

The characters Le père Goriot, (1750-1820) a grain merchant and manufacturer of vermicelli and pasta from Italy, who married the daughter of a Brie farmer. Anastasie Restaud, born around 1791, daughter of Monsieur Goriot, wife of Comte de Restaud. Delphine Nucingen, born in 1792, daughter of Monsieur Goriot, wife of the upper-middle-class banker Nucingen. Eugène de Rastignac, Eugène de Rastignac comes from a noble Angoumois family, represented by a Baron de Rastignac who lives near Angoulême and married a woman I don’t know who, hence Eugène, born in 1798, student then minister and count. In 1838, he married Augusta de Nucingen, Delphine’s daughter. From this union came Laure-Rose, born in 1801, and Agathe, born in 1802. Both married, one (Laure or Agathe) to Martial de la Roche-Hugon, the other unknown. Mme Couture, widow of a Commissaire-Ordonnateur of the French Republic and adoptive mother of Victorine Taillefer. She is one of the boarders at the Maison Vauquer. Miss Victorine Taillefer, abandoned by her father Frédéric Taillefer, a food supplier and later banker, born in 1779 and died in 1831, is taken in by Madame Couture at the bourgeois Vauquer boarding house. Victorine’s father, married twice, has a first-born son: Frédéric, killed in a duel by Franchessini and Victorine. Mr. Poiret, retired from the Ministry of Finance and intern at the Vauquer pension. M. Vautrin, real name Jacques Collin, born 1779, escaped convict and criminal known as Trompe-la-mort, then head of the Sûreté. Boarder at the Vauquer boarding school. Mlle Michonneau, Christine-Michelle, wife of Poiret and boarder at the Maison Vauquer. Mme Vauquer, née de Conflans, owner of the Pension Vauquer, born in 1765. Père Goriot is a novel in which money and worldly vanity are the mainsprings of action. At the same time, it’s a symbolic drama whose characters are the victim, old Goriot, the cynical and rebellious M. Vautrin, and the witness Rastignac. This drama is presented through the eyes of Rastignac, who has come from the provinces to attend law school, and discovers the world as it really is: venal, vain, unsentimental.

Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

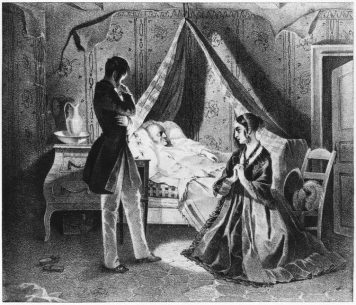

Father Goriot in agony

Delphine de Nucingen between her lover Eugène de Rastignac and her old father Jean-Joachim Goriot.

No Comments