A Woman of Thirty

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Fifteenth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1874) Scenes from private life

THE THIRTY-YEAR-OLD WOMAN

Analysis of the work La Femme de trente ans is one of Balzac’s best-known titles, and one of his most uneven works. It’s the conditions under which it was written that explain the inequalities of tone and quality that can be seen between the different parts. What we read today under the title La Femme de trente ans is the definitive text, finalized by Balzac in 1842 for the edition of La Comédie Humaine, of a work that had had several presentations since its first publication in 1832. Here are the sentences from this essay. Balzac’s Scènes de la vie privée (Scenes from private life ), written from 1830 onwards, were an illustration of the Physiology of Marriage. Balzac declared that he had written the short stories in this collection to warn girls and young women against the outbursts of their imagination, which could jeopardize their whole lives. In 1830, with this in mind, he had begun a short story, not completed until September 1831, entitled Le Rendez-vous (which Balzac later changed to Premières fautes). The aim of this short story was to show how a young girl can ruin her life with a moment of infatuation for a handsome officer, in which she will discover a farcical, insensitive and pretentious husband. A few months later, at the beginning of 1832, Balzac published two short stories in the Revue de Paris that had nothing to do with Le Rendez-vous. One of these short stories was called Les deux rencontres, the other Le Doigt de Dieu. As luck would have it, Les Deux rencontres appeared before Le Doigt de Dieu, but this was of no importance, since the two stories had no more to do with each other than they did with Le Rendez-vous. Le Doigt de Dieu (God’s Finger ) recounted an atrocious crime, a child’s crime disguised as an accident: a little boy, out of jealousy, pushed his younger brother into the Bièvre during a walk and drowned him. We understood that this jealousy had its origins in a clear preference on the part of the mother for one of the two children. In Les Deux rencontres, a fugitive who has just killed to avenge his father, pressed by his pursuers, comes to an unknown house for protection. The daughter of the house, who seems overwhelmed by secret remorse, discovers in this fugitive an unfortunate man who, like herself, has put himself outside the community of other men. She’s overwhelmed by this fate similar to her own. She runs off with this stranger. The man she loved became a hero of Bolivar’s liberation movement, he sailed the seas to block the coasts, she shared his destiny, she accompanied him, she was happy. While attacking a merchant ship, this privateer found the girl’s father among the passengers, recognized him, spared his life and had him disembarked: it was the first meeting. Several years later, the daughter, after a shipwreck in which her husband perished, was able to reach the Spanish coast and cross the border, where she was taken in, along with her youngest child, in a hotel in a spa village. She finds her mother by chance in the hotel and dies in her arms. Seemingly unrelated to the two previous news items. The reader senses a mystery in the girl’s past that is not explained. It was only then, a few months later, in October 1831, that Le Rendez-vous appeared in La Revue de Paris. This intimate short story was one of Balzac’s best studies of female psychology. Balzac boldly describes a situation about which most women remain silent, the disappointments of married life that soon lead to a distaste for conjugal intimacy, the young woman’s courage to keep up appearances, the husband’s nullity and selfishness, his indifference, and soon his abandonment when the birth of a child offers a glimpse of hope. Then, torpor, disgust with life, despite the child. This discolored life, with no light and no future, is transformed when the young woman discovers that a man secretly loves her, that he can be admitted to her. This platonic love is a rebirth. The joy of living, the light returned, all the youth awoke in this soul that had lost its strength. This white love ends in tragedy: the husband’s unexpected return, a moment of panic, a freezing night on a balcony, all lead to the death of the man who was for this woman all the poetry and nobility of love. Balzac had his spokesman Félix Davin say: “In no part of his work was M. de Balzac bolder or more complete. Le Rendez-vous is one of those impossible subjects that only he could tackle…”.

In Julie’s room

Sainte-Beuve himself, who disliked Balzac, made an exception in favor of Le Rendez-vous, which he called “a little masterpiece”, a predilection that Paul Bourget, Alain and André Maurois also affirmed. There is nothing in these three short stories, so different in tone and inspiration, to invite the reader to link them together. The names of the characters were different, some of them were designated by initials, and no allusion in this first state of the three stories referred from one to the others. A fourth short story, which was no more explicit than the previous ones, appeared in April 1832 in the Revue de Paris under the title La Femme de trente ans, a title later used for the novel and replaced by A trente ans. Once again, another name was used to designate the heroin. She is a young woman whose great love was shattered by the untimely death of her lover, and who has withdrawn from the world for several years. A young diplomat falls in love with her. A friendship develops between them, followed by tenderness. The story doesn’t conclude, it ends with a stupid word from the husband. But we guess… And the reader also guesses, for the first time, that there may be a link between this short story and Le Rendez vous : but he guesses thanks to a very strange ambiguity. Balzac has a model for this portrait. The Marquise he portrays is, of course, the Marquise de Castries, whom he will join in Aix-les-Bains a few months later. She was famous for her affair with the son of Chancellor Metternich, whose untimely death had shattered her life. One sentence in the short story alludes to this death. The reader is confused: he thinks it’s an allusion to the denouement of Le Rendez-vous. This confusion was not unintentional. A month later, in fact, Balzac combined the four short stories into a single volume in the second edition of Scènes de la vie privée. But when we put this volume together, we realized that the “copy” provided by the four short stories was insufficient. He soon had to compose a fifth short story, which he entitled L’Expiation (Atonement). An old, worried woman sees the last of her children, a daughter she adores and had by her lover, become the mistress of his son. She arrives too late to confess everything to her daughter and dies of grief. This volume of the second edition of Scenes from Private Life had no general title. Like the other three volumes, it was ostensibly a collection of short stories. But at the head of this tome, Balzac had placed a Editor’s notewhich clearly defined his intention: “I had asked the author to entitle this last volume Sketch of a woman’s lifeThe same character disguised under different names, the same life captured at its beginning, brought to its conclusion and portrayed with great moral purpose. “The note went on to state that the author had preferred to trust the intelligence of his readers. It wasn’t clear what was meant. In Le Rendez-vous (now known as Premières fautes), Balzac’s original point about a young girl being wrong to marry without heeding her father’s warnings was not at all original. He repeated this in all the short stories he wrote in 1830. But later, and even more so in La Femme de trente ans (now called At the age of thirty), he made a plea for women who are denied happiness both when they make the wrong choice themselves or when a marriage of convenience is imposed on them: even a pure, irreproachable attachment can be the cause of disaster for them. After this plea, Balzac seemed to deal with an entirely different theme, showing in The Finger of God and The Two EncountersThe tragic consequences of adultery on the destiny of children, the jealousies and hatred that the mother’s visible preference can lead to, and the domestic dramas that arise from these situations. But these consequences of an adultery that was only hinted at were so strange and exceptional that the reader was inclined to take them for imaginary.  These juxtaposed fates, attributed to different couples, obscured the author’s “great moral purpose”. Balzac decided to be clearer in the third edition of Scènes de la vie privée, published in 1834. He gave his five short stories the general title Même histoire, a more explicit indication than the modest 1832 Editor’s Note. But a new misfortune befell Balzac. The justification for this new edition was not the same as that of 1832: once again, the tome was found to be too short, and additions had to be made. Balzac made the most of this circumstance. He added a short story, Souffrances inconnues, which became the second in the collection and followed on from Rendez-vous. This short story showed the despair of a young woman who has just lost the man she loved without having given herself to him, who lives alone, deliberately estranged from her husband, unable to love the broken daughter she had from him. An old priest tries to bring her back to religion, but fails and foretells a sinister destiny. This connecting short story establishes a filiation between the first short story and those that follow. But above all, it gives a new force to the plea for women by an indictment of marriage of convenience much more violent and absolute than that of the Physiology of marriage. Concluding this new episode, Balzac wrote to Madame Hanska: “You will read Unknown sufferings that cost me four months of work; they are forty pages long: I didn’t write two pages a day… It’s so true that it makes you shudder. I have never been so moved by a work of art. This new presentation, which also included several editions designed to clarify the correspondence between episodes, was only a transitional version. La Femme de trente ans was not given its definitive form until 1843, when Balzac corrected it again for inclusion in his major edition of La Comédie humaine. The title of the novel appeared for the first time, the titles of the various short stories were changed to chapter headings, the names of the characters were changed and all the episodes became moments in the same destiny, that of Mme d’Aiglemont. Numerous detailed alterations, in addition to those carried out in 1834, gave greater unity to the whole. Viscount de Lovenjoul, the famous collector who was Balzac’s first exegete, gave an excellent explanation for this late unification. As the first episode in this woman’s life took place in 1813, it was impossible to speak of her “old age” as a guilty mother before the 1843 edition. Whatever Balzac’s skill, these corrections could not erase the differences in tone and verisimilitude that existed between the intimate parts of the novel and the adventures of the later parts. Balzac was aware of these irreparable difficulties. Rereading Les Deux rencontres for this 1843 reprint, he sadly confessed to Madame Hanska: “I haven’t had the time to remake this melodrama, which is unworthy of me. My heart as an honest man of letters still bleeds from it.” Autre étude de femme, which we place here, is another example of Balzac’s composite works. It was first published in 1842 to provide a sufficient number of pages for Volume II of The Human Comedy But with the exception of the staging, designed to introduce the characters, the entire story is made up of tales written by Balzac ten years earlier, in 1832, and already published in magazines or used in other works. The beginning alone is from 1842: it’s a conversation between witty people at the end of a supper, a montage frequently found in Balzac’s work. Henri de Marsay, Balzac’s most brilliant dandy, recounts his first female adventure. It’s called Les Premières armes d’un lion (The First Weapons of a Lion), a title used shortly afterwards for a new edition. Conversation ensues between the guests, and it’s this witty, lively exchange, in which each brings his or her own anecdote, that allows the novelist’s back drawers to be inserted. A few fragments ofUne conversation entre onze heures et minuit published in 1832 in the collective collection of Brown tales and La Mort de la duchesse , a short fragment of the same origin, is finally the bravura piece, La Grande Bretèche or Les Trois vengeances, and finally in The department’s Muse.

These juxtaposed fates, attributed to different couples, obscured the author’s “great moral purpose”. Balzac decided to be clearer in the third edition of Scènes de la vie privée, published in 1834. He gave his five short stories the general title Même histoire, a more explicit indication than the modest 1832 Editor’s Note. But a new misfortune befell Balzac. The justification for this new edition was not the same as that of 1832: once again, the tome was found to be too short, and additions had to be made. Balzac made the most of this circumstance. He added a short story, Souffrances inconnues, which became the second in the collection and followed on from Rendez-vous. This short story showed the despair of a young woman who has just lost the man she loved without having given herself to him, who lives alone, deliberately estranged from her husband, unable to love the broken daughter she had from him. An old priest tries to bring her back to religion, but fails and foretells a sinister destiny. This connecting short story establishes a filiation between the first short story and those that follow. But above all, it gives a new force to the plea for women by an indictment of marriage of convenience much more violent and absolute than that of the Physiology of marriage. Concluding this new episode, Balzac wrote to Madame Hanska: “You will read Unknown sufferings that cost me four months of work; they are forty pages long: I didn’t write two pages a day… It’s so true that it makes you shudder. I have never been so moved by a work of art. This new presentation, which also included several editions designed to clarify the correspondence between episodes, was only a transitional version. La Femme de trente ans was not given its definitive form until 1843, when Balzac corrected it again for inclusion in his major edition of La Comédie humaine. The title of the novel appeared for the first time, the titles of the various short stories were changed to chapter headings, the names of the characters were changed and all the episodes became moments in the same destiny, that of Mme d’Aiglemont. Numerous detailed alterations, in addition to those carried out in 1834, gave greater unity to the whole. Viscount de Lovenjoul, the famous collector who was Balzac’s first exegete, gave an excellent explanation for this late unification. As the first episode in this woman’s life took place in 1813, it was impossible to speak of her “old age” as a guilty mother before the 1843 edition. Whatever Balzac’s skill, these corrections could not erase the differences in tone and verisimilitude that existed between the intimate parts of the novel and the adventures of the later parts. Balzac was aware of these irreparable difficulties. Rereading Les Deux rencontres for this 1843 reprint, he sadly confessed to Madame Hanska: “I haven’t had the time to remake this melodrama, which is unworthy of me. My heart as an honest man of letters still bleeds from it.” Autre étude de femme, which we place here, is another example of Balzac’s composite works. It was first published in 1842 to provide a sufficient number of pages for Volume II of The Human Comedy But with the exception of the staging, designed to introduce the characters, the entire story is made up of tales written by Balzac ten years earlier, in 1832, and already published in magazines or used in other works. The beginning alone is from 1842: it’s a conversation between witty people at the end of a supper, a montage frequently found in Balzac’s work. Henri de Marsay, Balzac’s most brilliant dandy, recounts his first female adventure. It’s called Les Premières armes d’un lion (The First Weapons of a Lion), a title used shortly afterwards for a new edition. Conversation ensues between the guests, and it’s this witty, lively exchange, in which each brings his or her own anecdote, that allows the novelist’s back drawers to be inserted. A few fragments ofUne conversation entre onze heures et minuit published in 1832 in the collective collection of Brown tales and La Mort de la duchesse , a short fragment of the same origin, is finally the bravura piece, La Grande Bretèche or Les Trois vengeances, and finally in The department’s Muse.

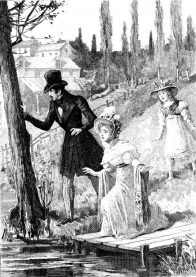

History Julie falls in love with Colonel Victor d’Aiglemont, a handsome man in whom she discovers an insensitive, pretentious husband. Balzac boldly describes a situation about which most women remain silent, the disappointments of married life to keep up appearances, the husband’s nullity and selfishness, his indifference, and soon his abandonment when the birth of a child, Hélène, offers a glimpse of hope. Then torpor, disgust with life, despite the child. This discolored life, with no light and no future, is transformed when the young woman discovers that a man secretly loves her, a young Englishman named Lord Arthur Grenville, and that he can be admitted to the family.  of her as a doctor. This platonic love is a rebirth for Julie. The joy of living, the light returned, all the youth awoke in this soul that had lost its strength. This love ends in tragedy. The husband’s unexpected return, a moment of panic and a freezing night spent on a balcony lead to the death of Arthur, who for Julie was all the poetry and nobility of love. Despite the motherhood she clings to, Julie doesn’t love her daughter Hélène, for whom she would like to see a different voice and different eyes. This child of a husband she can’t stand is unbearable for her. From this union, Julie also had a son, Charles, who was her favorite. During a family outing, unbeknownst to the adults, Hélène pushed Charles in a fit of rage, causing him to fall, tumble down the embankment and drown in the bed of the Bièvre. Everyone will think it’s an accident, and Hélène will always keep it a secret. Julie would have two more children: Abel and Moïna. We learn that Moïna was born of her affair with the diplomat and Marquis Charles de Vandenesse. One evening, a fugitive who has just killed to avenge his father, pressed by his pursuers, comes to Colonel d’Aiglemont for protection. Overwhelmed by this secret remorse, and unhappy with a mother who rejects and humiliates her, Hélène runs off with this stranger. The man she loved became a hero of Bolivar’s liberation movement. It scours the seas to block coasts. Hélène shares his destiny and accompanies him. She’s happy. Attacking a merchant ship, this privateer finds Hélène’s father (Victor d’Aiglemont) among the passengers. He recognizes him, spares him and sends him off: it’s the first encounter with the father. Several years later, Hélène, after her husband was shipwrecked on the Othello, was able to reach the Spanish coast and cross the border. She was taken in, exhausted with her last child, in a hostelry in a spa village. There she met up with her mother and sister Moïna, who had come to take the waters. Hélène dies in her mother’s arms. The end of the story could be called L’expiation (Atonement), although the last part is entitled La vieillesse d’une mère coupable (The Old Age of a Guilty Mother). In her old age, Julie bequeaths her entire fortune to her favorite daughter Moïna. She lives under the yoke and despotism of this spoiled child. Moïna shows nothing but indifference and contempt for her mother, from whom she accepts no advice. This poor mother sees her last child, her beloved daughter from her lover the Marquis de Vandenesse, become the mistress of his son. She arrives too late to confess everything to her daughter and dies of grief. After suffering a heart attack, Julie died without being able to speak again. Paris 1828-1844

of her as a doctor. This platonic love is a rebirth for Julie. The joy of living, the light returned, all the youth awoke in this soul that had lost its strength. This love ends in tragedy. The husband’s unexpected return, a moment of panic and a freezing night spent on a balcony lead to the death of Arthur, who for Julie was all the poetry and nobility of love. Despite the motherhood she clings to, Julie doesn’t love her daughter Hélène, for whom she would like to see a different voice and different eyes. This child of a husband she can’t stand is unbearable for her. From this union, Julie also had a son, Charles, who was her favorite. During a family outing, unbeknownst to the adults, Hélène pushed Charles in a fit of rage, causing him to fall, tumble down the embankment and drown in the bed of the Bièvre. Everyone will think it’s an accident, and Hélène will always keep it a secret. Julie would have two more children: Abel and Moïna. We learn that Moïna was born of her affair with the diplomat and Marquis Charles de Vandenesse. One evening, a fugitive who has just killed to avenge his father, pressed by his pursuers, comes to Colonel d’Aiglemont for protection. Overwhelmed by this secret remorse, and unhappy with a mother who rejects and humiliates her, Hélène runs off with this stranger. The man she loved became a hero of Bolivar’s liberation movement. It scours the seas to block coasts. Hélène shares his destiny and accompanies him. She’s happy. Attacking a merchant ship, this privateer finds Hélène’s father (Victor d’Aiglemont) among the passengers. He recognizes him, spares him and sends him off: it’s the first encounter with the father. Several years later, Hélène, after her husband was shipwrecked on the Othello, was able to reach the Spanish coast and cross the border. She was taken in, exhausted with her last child, in a hostelry in a spa village. There she met up with her mother and sister Moïna, who had come to take the waters. Hélène dies in her mother’s arms. The end of the story could be called L’expiation (Atonement), although the last part is entitled La vieillesse d’une mère coupable (The Old Age of a Guilty Mother). In her old age, Julie bequeaths her entire fortune to her favorite daughter Moïna. She lives under the yoke and despotism of this spoiled child. Moïna shows nothing but indifference and contempt for her mother, from whom she accepts no advice. This poor mother sees her last child, her beloved daughter from her lover the Marquis de Vandenesse, become the mistress of his son. She arrives too late to confess everything to her daughter and dies of grief. After suffering a heart attack, Julie died without being able to speak again. Paris 1828-1844

Genealogy of characters D’Aiglemont: Marquis Victor d’Aiglemont (1783-1833). Married Julie de Chastillonnest (1797-1844), from whom : Hélène born 1817, died around 1833. Kidnapped by the pirate Victor, four children died young; Charles killed by Hélène; Gustave, who died young, leaving a widow and children; Moïna who married Saint-Héreen ; Abel killed in front of Constantine. We can assume that, with the exception of Hélène, these children were born of their mother’s affair with Charles de Vandenesse. For this family, all dates are approximate. Grenville: Arthur, Ormond, lord. Englishman died in 1823. Vandenesse: Noble Touraine family represented by a Marquis de Vandenesse, who died around 1827. Married a Listomère, hence : Charles, count then marquis, diplomat born in 1790. Wife Emilie de Fontaine, widow Kergarouët, from whom at least one son, Alfred. Charles was also the father of Mme d’Aiglemont’s last four children; Félix, viscount then count, born in 1794. Wife Marie-Angélique de Grandville born 1808, from whom : a daughter who married Listomère, another girl. We should also mention an Abbé de Vandenesse, a great-uncle of the above.

1) Source analysis/history: Preface, taken from Volume V, compiled from the complete text of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

2) Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde – Gallimard”.

No Comments