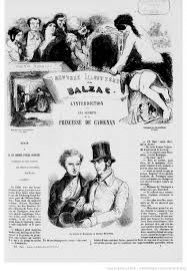

The Secrets of the Princess Cadignan

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Eleventh volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877) Scenes from Parisian life

THE SECRETS OF THE PRINCESS OF CADIGNAN Dedicated by Balzac, TO THEOPHILE GAUTIER

Analysis of the work Great friend of Balzac Théophile Gautier, born in Tarbes in 1811, is a French writer. Partisan of Romanticism at the Battle of Hermani, art and theater critic, author of travel accounts, such as Tra los montes in 1843, fantasy short stories and novels Mademoiselle de Maupin in 1835, Captain Fracasse in 1863, he defended “art for art’s sake” in poetry Emaux et Camées 1852). He died in Neuilly in 1872. Théophile Gautier supported Balzac on January 11, 1849, when the Académie Française elected the Duc de Noailles to Chateaubriand’s seat as a writer by 25 votes out of 51. Balzac was awarded 4 – those of Victor Hugo, Lamartine, Empis and Pongerville. Three days after the election of the Duc de Noailles, the Théâtre du Gymnase dramatique premiered Madame Marneffe ou le Père prodique, a five-act play by Louis Clairville (1811-1876), adapted from La Cousine Bette with Balzac’s consent, to whom a third of the royalties were due. Reporting on this piece in La Presse of January 15, Théophile Gautier protested against the “mere four votes” Balzac had just received at the Académie, praising “his European reputation”, his “immense talent”, his “genius” and adding: ” The Divine Comedy is no more complete for the invisible world than The Human Comedy for the real world”. This did not impress the 27 voting academicians, who on January 18 needed three rounds of voting to elect the Count de Saint-Priest to Jean Vatout’s seat, with 14 votes. Balzac received 2 votes in succession (Hugo and Vigny).

Princesse de Cadignan

Théophile Gautier, Balzac’s great admirer and friend, learned of his friend’s death in Venice, when he opened the Journal des Débats , “one of the few French newspapers to penetrate Venice”, at the Café Florian in Place Saint-Marc, and was unable to send an article to La Presse. One of Balzac’s most famous short stories paints a very different picture, The secrets of the Princess of Cadignan. Marcel Proust admired her and remembered her so well that he had Albertine wear a toilette reminiscent of the one Diane de Cadignan had made for d’Arthez. Paul Bourget and André Maurois, after him, ranked it among Balzac’s best short stories. However, as Anne-Marie Meininger states in a very fine and learned presentation of this work: “Balzac invents nothing, here less than ever”, and she adds: “the life of an authentic parisian princess – first title of this short story – dictated to him the story of Diane de Cadignan”. This is the opposite of Splendeurs et décadence des courtisanes, a novel in which Balzac invented a drama and dramatic characters, whereas here he invents by faithfully following a real-life model. Written in June 1839, Balzac’s short story was summed up by the author himself to Madame Eve Hanska: “This is the greatest moral comedy in existence. It’s the pile of lies by which a thirty-seven-year-old woman, the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse, who became Princess of Cadignan by succession(on the death of her father-in-law) manages to make her fourteenth adorer take her for a saint, a virtuous, a modest young girl, it is finally the last degree of depravity in the feelings… The masterpiece is to have made see the lies as just, necessary and to justify them by love. This is one of the diamonds in the crown of yours truly.” In his fine presentation, which summarizes research published in 1962 in L’Année BalzacienneAnne-Marie Meininger shows the obvious parallels between Cordélia de Castellane, née Greffulhe, daughter of a wealthy Geneva banker, married at seventeen to the much older Comte de Castellane, and Balzac’s Diane d’Uxelles, born the same year and married at the same age to the Comte de Maufrigneuse, a husband just as fickle as Castellane and just as unconcerned about his wife’s conduct. The fortune of the graceful Swiss lady was as radically squandered by the Comte de Castellane as that of Diane de Maufrigneuse by her husband. In exchange, both enjoyed total freedom, from which they benefited equally. And, having grown wise, both led a discreet lifestyle in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, wisely and diligently looking after the establishment of their sons, Georges de Maufrigneuse and Henri de Castellane, who went on to make the same brilliant marriage. At the age of thirty-seven, the Comtesse de Castellane succeeded in winning over Count Molé, who had been a prestigious President of the Council under King Louis-Philippe, a feat of feminine high school that Balzac had the Princesse de Cadignan achieve under the same conditions with the only equivalent he considered worthy of a Prime Minister, the great writer Daniel d’Arthez, in whom Balzac himself must be recognized. This lovely feminine comedy certainly deserved Marcel Proust’s admiration. But how could the ironic photographer of Madame Verdurin’s language or that of Oriane de Guermantes not be bothered by the amphigoric, pretentious phrases so unexpected in the witty Maufrigneuse of the Cabinet des Antiques ? This pathos of the duchesses is the only part of Balzac’s work that has really aged. And Balzac uses it a little too generously in this seductive enterprise.

The story Diane de Maufrigneuse, who became Princess of Cadignan on the death of her father-in-law, took advantage of the July Revolution of 1830, which destroyed several aristocratic fortunes supported by the Court, as a pretext for the complete ruin of her house caused by her inconsistencies and profligacy. With the prince exiled from France along with the royal family, Diane de Cadignan retreated under her new identity, far from the world and the glitz of the salons, to assume the role of accomplished mother and devote herself totally to the education of her son Georges. The enormous sacrifices made by this coquette have a purpose – to hide from the world the exact state of her financial annihilation, but also because she is reaching the age of thirty-seven and wants to bury her coquettish socialite existence for good. This new existence, this apparent redemption of “good behavior”, is a hypocritical façade to transpose the sulphurous personality of the Countess de Maufrigneuse “into a Diane de Cadignan beyond reproach. This heartless, feminine Don Juan who has never loved attempts, with the help of his friend the Marquise d’Espard, a final game of seduction with the poet Daniel d’Arthez, now a baron and famous writer. It was during a conversation between the two that Madame d’Espard suggested that her friend introduce her to the young poet. For Diane, it’s the ultimate opportunity to love and be loved. An affabulatrice and manipulator of the highest order, Diane seduces Daniel d’Arthez by assuming the role of victim: her unhappy childhood with a coquettish, unfaithful mother – her forced marriage to her mother’s noble lover – the latter’s disdain and “mesmerism” towards her – her love affairs with men who didn’t deserve her – the bad luck that was always on her side, and which robbed her of the sincere feelings of the only man who truly loved her, Michel Chrestien, whose life was unfortunately taken in his youth. Michel Chrestien, friend of Baron Daniel d’Arthez. This socialite will do everything in her power to sensitize and entice the poet’s pure, naive heart. Convinced and moved by the charisma and “authenticity of emotion” perceptible in this great lady, Daniel fell passionately in love with her. The good taste, culture and finesse of this sublime woman make her a divine angel in the eyes of the poet.  Driven by curiosity, Madame d’Espard learns when she comes to ask about her friend that she is spinning the most charming of fairy tales. Women united by the same misfortune support each other, but if one of them aspires to absolute happiness, long coveted and never found, there’s a good chance that this false friend will be your enemy tomorrow. Envious of her friend’s happiness, Madame d’Espard organizes an “intimate” evening, to which she invites not only Daniel d’arthez, but also most of her guests, who are said to be former lovers of Diane. The assembly was made up of the most perfidious people: Eugène de Rastignac, Emile Blondet, the Marquis d’Ajuda-Pinto, Maxime de Trailles, the Marquis d’Esgrignon, the two Vandenesses, du Tillet, the Baron de Nucingen, the Chevalier d’Espard, Nathan and Lady Dudley. As Madame d’Espard had foreseen, and without any need for her to intervene, half-tone jibes and witticisms about the existence of the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse soon became the main topic of the evening. Daniel d’Arthez, will defend the princess with dignity and emerge the stronger in the eyes of the guests. D’Arthez has shown that he’s not the gullible, stupid man everyone expected him to be. He’s psychologically astute and intelligent. Having inherited some of her mother’s fortune, Diane deserted Paris for the summer months to live in Geneva with her great writer, only to return in the winter months. It’s not recorded how long their romance lasted. Aux Jardies, June 1839

Driven by curiosity, Madame d’Espard learns when she comes to ask about her friend that she is spinning the most charming of fairy tales. Women united by the same misfortune support each other, but if one of them aspires to absolute happiness, long coveted and never found, there’s a good chance that this false friend will be your enemy tomorrow. Envious of her friend’s happiness, Madame d’Espard organizes an “intimate” evening, to which she invites not only Daniel d’arthez, but also most of her guests, who are said to be former lovers of Diane. The assembly was made up of the most perfidious people: Eugène de Rastignac, Emile Blondet, the Marquis d’Ajuda-Pinto, Maxime de Trailles, the Marquis d’Esgrignon, the two Vandenesses, du Tillet, the Baron de Nucingen, the Chevalier d’Espard, Nathan and Lady Dudley. As Madame d’Espard had foreseen, and without any need for her to intervene, half-tone jibes and witticisms about the existence of the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse soon became the main topic of the evening. Daniel d’Arthez, will defend the princess with dignity and emerge the stronger in the eyes of the guests. D’Arthez has shown that he’s not the gullible, stupid man everyone expected him to be. He’s psychologically astute and intelligent. Having inherited some of her mother’s fortune, Diane deserted Paris for the summer months to live in Geneva with her great writer, only to return in the winter months. It’s not recorded how long their romance lasted. Aux Jardies, June 1839

Main characters La princesse de Cadignan: Noble family represented by an elderly prince of Cadignan, who died in 1830. He fathered a daughter, who married the Duc de Navarreins, and a son, born around 1776, who was Duc de Maufrigneuse until 1830, then Prince de Cadignan. In 1814, this son married Diane d’Uxelles, born in 1796, duchesse de Maufrigneuse, then princesse de Cadignan. This union gave birth to Georges de Maufrigneuse around 1815, who married Berthe de Cinq-Cygne. The Duchesse de Maufrigneuse and Princesse de Cadignan is a former socialite of the Faubourg Saint-Germain. The House of Cadignan, which holds the title of Duc Maufrigneuse for its eldest sons and Chevaliers de Cadignan for its youngest. The Cadignan family bears Or, five fusils fesswise conjoined Sable, with the word MEMINI as motto. This illustrious house was ruined after the July Revolution of 1830, and the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse, who became Princess of Cadignan on the death of her father-in-law, withdrew from society life in order to forget her sulphurous past as a socialite coquette than to restore his image of necessary probity at the dawn of his old age. A manipulator and comedienne at heart, she exonerates herself so well from the dishonorable behaviors of the Duchesse de Maufrigneuse’s past, and makes herself look so much like a victim of life to her lover Daniel d’Arthez, that she completely wins the admiration and heart of this great man.

Diane de Maufrigneuse, Princess of Cadignan

La marquise d’Espard : a superior and noble woman from the Faubourg Saint-Germain, highly respected at court. Illustrious by birth, a Blamont-Chauvry, she has all the assets of a superior woman. She is a friend of the Princesse de Cadignan. Very close and complicit in the events of their intimate lives, they confide in each other and support each other – even as they confide in each other that they have never met true, great love – innocent, unconditional love. Mme d’Espard, who had already met the great writer Daniel d’Artez, offered to introduce her to this talented, hard-working and serious young man. Daniel d’Arthez: (1794) A penniless student living at the Pension Vauquer, Daniel d’Arthez inherits a family fortune that elevates him to the rank of baron. A serious writer and a hard worker, Daniel, despite his fortune, doesn’t share the glamour of the rich: he lives comfortably while continuing his obligations and his literary work. He’s also a politician. Eugène de Rastignac: (1798) student, then minister and count. Born into a noble Angoumois family represented by a Baron de Rastignac who lives near Angoulême. In 1838, Eugène married Augusta de Nucingen. Eugène was one of the dandies, an elegant man who frequented the capital’s most famous salons. Maxime de Trailles: (presumed birth 1792) Count and dandy who, like Eugène de Rastignac, belongs to the family of lions, i.e. the race of seigneurs. A witty individual, he was the phoenix of Parisian salons. He marries a woman we have every reason to believe is Cécile Beauvisage.

Sources analysis/history: 1) Roger Pierrot “Honoré de Balzac” published by Fayard in February 1999.

2) Preface to Volume XIV, based on the full text of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

Source: 1) Félicien Marceau, entitled Balzac et son monde (Gallimard) – 2) Wikipedia, the universal encyclopedia.

No Comments