Gaudissart II

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Twelfth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877) Scenes from Parisian life

GAUDISSARD II Short story written in November 1844

Signed TO THE PRINCESS CRISTINA DE BELGIOJOSO née TRIVULCE

Analysis of the work On Gaudissard II which was published almost simultaneously in the daily newspaper La Presse and in Hetzel’s collection, The Devil in Paris, there’s nothing to say that hasn’t already been said aboutA businessman. It’s a quick sketch of an everyday scene in Parisian commerce: the aim is to sell a shawl to an Englishwoman, a difficult and vain customer. This amusing scene, presented with vivacity and mischief, would provoke no particular comment were it not for the opportunity to pay tribute to the precision and ingenuity of the researchers who are endeavoring to reconstruct the genesis of these stories, which at first glance appear to be brilliant improvisations by the novelist. An excellent investigation by Anne-Marie Meininger is a significant example of the discoveries that can be made by comparing a moment in Balzac’s life with a work that simply inspired him in his usual walks and strolls. We realize that Gaudissard II is not just a sketch taken on the spot, but a “thing seen” that chance presented to Balzac, which he enjoyed, recorded and staged. He was a frequent visitor to his publisher Hetzel, who had just opened a bookshop at 76, rue de Richelieu. The Devil in Paris and the current volumes of The Human Comedy. In the same building was a brilliant novelty store, under the sign of the Persian, as in the novella: shawls were sold, and with such success that the store owner soon bought the premises occupied by Hetzel and retired a few years later, having amassed a comfortable fortune. This shrewd merchant was called Lavanchy, but his name has not gone down in history. But on the other side of the street lived an owner named André Germain Gaudissard. Balzac rightly considered that the name belonged to him as well as to its bearer. He gave it to his shawl merchant, who thus became the successor to L’Illustre Gaudissart, whom Balzac’s readers had already accompanied on his campaigns in the Vouvray district. So Balzac had found his ready-made scene. But there were details to invent, characters to bring to life – the salesmen, the trader himself – a whole scene to “set up”. Balzac took no further trouble with this part of his work. Anne-Marie Meininger, who knows the literary dabblers of Louis-Philippe’s time as well as the archive files, has found in Lhe Book of One hundred and one published in 1834 a sketch by Auguste Luchet that already dealt with Balzac’s chosen subject and provided him with the setting and characters he needed. It’s easy to see why Balzac could write to Madame Hanska, referring to the easy scenes that were so successful: “I had my Diable articles stapled in a moment. These amusing medallions are not, as much as one might think, on the bangs of La Comédie Humaine. Gaudissart II completes the picture of Parisian commerce, marking the end of an evolutionary process. In the beginning, there’s the still-patriarchal La Maison du chat qui pelote, which the worthy M. Guillaume abandoned in 1811. Later, La Reine des Roses, César Birroteau’s store, shows a merchant under the Restoration, decorated, important, launching his products. Finally, Gaudissart II provides the last image, that of the big shopkeeper who lives amid the gilding, in the glitz of a sumptuous store, under the protection of an exotic sign, heralding the reign of the prospectus and the triumph of advertising.

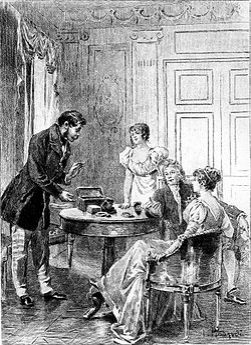

The Story A very “collet-monté” Englishwoman turns up at Persan, a large novelty store specializing in shawls, with the intention of buying a beautiful item at a low price. Everything beautiful is shown to her, but nothing seems beautiful enough, and everything seems too expensive. After showing him his most beautiful pieces, the clerk displays inferior products, claiming that these refined luxury items are more expensive than the models he has presented. After demonstrating all the shawls, scarves and squares likely to interest his haughty customer, and after countless unsuccessful fittings, the clerk forfeits and announces that he has nothing left. At this point, the boss, who hadn’t missed a thing, intervened and offered him his last shawl: a very rare shawl, one of the seven Selim had given to Emperor Napoleon. Her curiosity and vanity whetted, the Englishwoman asked to try it on. In fact, it’s an old unsold item that’s gone out of fashion because it’s no longer up to date. This old-fashioned shawl, valued at fifteen hundred francs, was eventually sold to him for six thousand, thanks to the merchant’s commercial talent. The delighted customer leaves the store, convinced she’s made a good deal, and the shopkeeper congratulates himself on having been able to sell a discarded item.

The characters Gaudissard II: Son of Félix Gaudissart, travel clerk and theater director, born in 1792. Jean-Jacques Bixiou: Caricaturist born in 1797 to his father Bixiou, grocer and first husband of Madame Descoings.

Source analysis: Preface from Volume XVI, compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

History source: Wikipedia, the universal encyclopedia. Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

No Comments