The Unwitting Comedians

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Twelfth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877) Scenes from Parisian life

THE UNWITTING COMEDIANS

Dedicated work, TO MONSIEUR LE COMTE JULES DE CASTELLANE

Analysis of the work Balzac had placed the set of sketches entitled Les Comédiens sans le savoir in Volume XII of the last edition of La Comédie Humaine, which was printed before his eyes. In this tome, this set followed on from Un homme d’ affaires and Gaudissart II , to which it is linked by inspiration. In reality, Les Comédiens sans le savoir is no more than a “montage” of Balzac’s articles, similar to those he had contributed to the editor Curmer’s collection Les français peints par eux-mêmes, which included L’Epicier, le Notaire, la Femme de province, which were not collected in The Human Comedy. Les Comédiens sans le savoir have been promoted to the rank of works of art. The Human Comedy because of one of those circumstances so frequent in the history of Balzac’s work: this tome XII of The Human Comedy was sorely lacking in copy, and Balzac crammed this series of articles into it to give it a sufficient number of pages. The sketches gathered under this title were originally “commissioned” by the publisher Hetzel for a collection entitled The Devil in Paris. In a contract dated August 17, 1844, Balzac promised Hetzel five separate articles, the first two of which were entitled Comedies you can see for free in Paris and All you can see in ten minutes on Boulevard des Italiens. These two titles perfectly define Les Comédiens sans le savoir. Finally, Hetzel received Diable à Paris two portraits of Comédiens, Un espion à Paris : le petit père Fromenteau, bras droit des gardes du commerce and Une marchande à la toilette are accompanied by Gaudissart II and Un homme d’ affaires, which were later published as separate Balzac short stories. Hetzel also authorized Balzac to contribute a third fragment, Le Luther des chapeaux, to Le Siècle. Balzac had the idea of arranging this raw material by presenting these portraits as the encounters of a provincial to whom two mischievous friends introduce him to the mysteries of Paris. This invention didn’t require too much effort. For a long time now, when describing the “House of the Cuddly Cat”, when discovering the Vauquer boarding house in Le Père Goriotby taking the reader inside a solicitor’s office, or watching the departure of a stagecoach in his new A start in life, Balzac had taken on the role of guide to the “curiosities” we pass by every day without seeing them: he was already “walking” his reader. His provinciality and his two mentors enabled him to include very brief encounters that couldn’t possibly provide the material for an article: rat de l’Opéra, a “marcheuse”, a “basse-taille”, the buvette de la Chambre des Députés, or to add indefinitely to the list of originals crossed by chance on the boulevard or reigning in their store: Chodoreille the little-known writer, Dubourdieu the thinking painter, Publicola Masson the revolutionary pedicurist, Vauvinet the elegant usurer. This “editing” is an easy exercise that is mostly akin to journalism. But this is Balzacian journalism: that is, journalism that deciphers signs in the seemingly eccentric aspects of the world before our eyes that we don’t know how to read. The hairdresser who steps forward with the dignity of a great artist, the hatmaker who dreams of promoting a revolution in hats, the elegant usurer with the manners of a petit maître, are not just originals. They heralded the reign of wealth, glitz and advertising, the bloat that would turn the merchant into a “trader” and the usurer into a broker: they were not just good guys, they were the pioneers of a changing world. This world interests Balzac because it’s changing. In Gaudissart II, he describes the movement of Parisian commerce towards the boulevards and the new methods that accompanied this annexation. And yet, in this change that heralds the future, we find the archeological Balzac of Paris, who discovered in the store of the “maison du chat qui pelote”, such a vivid and telling image of the past, of a past that was disappearing. Showing what appears to be the future in new ways and new stores is the same investigation as that which consists in finding the already obsolete traces of the past: it’s the real history of manners, the one that gives it a title to be something other than anecdotal. And this, along with his verve and irony, is what makes Les Comédiens sans le savoir so interesting even today. As Balzac moved from discovery to discovery, this provincial interested a publisher, Gabriel Roux, who had taken over Balzac’s contracts with Chlendowski. This publisher saw a speculation. The title, Le Provincial à Paris, had been known since the 18th century, and had the added merit of reminding us of the sketches in Jouy’s L’Hermite de la Chaussée d’Antin, which had been immensely successful in the final years of the Empire. On this occasion, Balzac showed the full extent of his skill, thanks to the use of blanks and chapter headings (Balzac succeeded in inventing a division into thirty chapters), beautiful pages and luxurious margins, and with the help of a copious eulogy of Balzac presented “en avant-propos”, he managed to produce two in-8° volumes under the title Le Provincial à Paris: followed by a reprint of two old short stories. This typographic feat was achieved in 1848. Balzac had been less successful with Volume XII of La Comédie Humaine, whose presentation did not allow for such fantasies. Les Comédiens sans le savoir was not long enough to complete the tome that the publisher of La Comédie Humaine had to complete its work by starting with the Scenes from political life.

Gazonal

The story Les Comédiens sans le savoir is a novel by Honoré de Balzac that appeared in pre-publication in 1846 in the Courrier français, and was published in volume the same year in the Scènes de la vie parisienne section of La Comédie humaine in the Furne edition. It was republished in 1848 by Roux and Castanet under the title Le Provincial à Paris. The novel presents a kind of “troupe review or dress rehearsal” of all the social types, silhouettes and characters from La Comédie humaine, caught on the spot, in action, in the most recurring geographical location: Paris. Sylvestre Palafox-Castel-Gazonal, known as Gazonal, “goes up” to Paris to settle a lawsuit against the prefect of his department, the Pyrénées-Orientales, which has been transferred to the Conseil-d’Etat. The main character’s adventures are a pretext for presenting a gallery of Balzacian portraits, from the “lorette” (the opera rat Ninette) to the newspaper editor (Théodore Gaillard), from the concierge Ravenouillet to the toilet trader (Madame Nourrisson). Reconnecting with his cousin Léon Didas y Nora, the facetious painter known as the Mistigris, pupil of Baron Hippolyte Schninner (the famous painter in “La Bourse”), sent to the château de Presles in A start in life who had become a famous landscape gardener and man of fashion, Gazonal also discovered the Paris of elegance at the “Café de Paris”. And with the help of Mistigris and his friends (including the seductive Jenny Cadine), Gazonal wins his case. In the background, we naturally find the characters essential to the world of La Comédie humaine: Eugène de Rastignac, Joseph Bridau, poet Melchior de Canalis, painter Dubourdieu, Carabine, businessmen Cérizet and Fernand du Tillet, horsewoman Malaga, Baron de Nucingen, Maxime de Trailles and others. It’s as if Balzac himself wanted to plunge back into his world and take stock of it. It’s more of a staging (very well staged) of a compilation of sketches and portraits. Gazonal presents himself as a kind of witness to La Comédie humaine, the real heroine of the novel being Paris and Parisian life in all its neighborhoods. “There are two Paris: the one of salons, suave atmospheres, silky fabrics, elegant neighborhoods, and the more hellish one, of orgies, dark alleys (Ferragus), miserable garrets.”

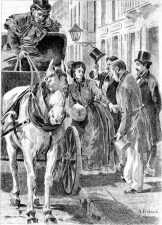

Mrs Nourrisson, toilet trader

The characters Gazonal: Sylvestre-Palafox Gazonal, lace manufacturer, cousin of Léon de Lora. Ninette : Little rat (dancer). Théodore Gaillard: newspaper manager, married Suzanne du Val-Noble. Ravenouillet: Caretaker and usurer. Madame Nourrisson: Toilet trader, usurer, matchmaker, owner of a brothel on rue Sainte-Barbe and a brothel on pâté des Italiens. Léon Didas y Nora or Léon de Lora: (1806) Spanish family based in Roussillon. Hippolyte Schninner: (1790) Painter ennobled baron, husband of Adélaïde de Rouville. Jenny Cadine: (1814) Actress.

Source analysis: Preface from Volume XVII, compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac. Topic source: Wikipedia.

Source for character genealogy: Félicien Marceau, author of “Balzac et son monde” published by Gallimard.

No Comments