César Birotteau

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Tenth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Madame César Birotteau

CESAR BIROTTEAU

Work dedicated by Balzac A MONSIEUR ALPHONSE DE LAMARTINE His admirer, DE BALZAC

Analysis of the work With César Birotteau and Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, we’re at the heart of Scènes de la vie parisienne, one of the most prestigious divisions of La Comédie Humaine . But, at the same time, these two works take Balzac’s readers into very different milieus, one that of the bourgeoisie and the other that of the underworld, with characters that are equally representative, but staged and lit in a dissimilar way: one depicts characters and existences that are still familiar to us, the other unusual adventures and extras that are foreign to our own experience. The subject of César Birotteau can be summed up in one word: it’s the story of a bankruptcy and a rehabilitation. Not just any bankruptcy, and not just any rehabilitation: that of an honest, successful and esteemed businessman, who suddenly fell victim to a commercial catastrophe caused by his confidence in his own prosperity, aggravated by imprudence, but who, in his liquidation, set an example of probity and scrupulousness that earned him general praise and a solemn ovation; he died of exhaustion in the midst of this triumph. The novel’s title is a representation in itself. Parodying the famous title chosen by Montesquieu, Balzac entitled this biography: Histoire de la grandeur et de la décadence de César Birotteau, marchand parfumeur, adjoint au maire du2e arrondissement de Paris, chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, etc. This majestic, mocking title conjures up an image: Balzac’s readers are immediately reminded of Joseph Prud’homme, the sententious bourgeois made famous by Henry Monnier’s caricatures. César Birotteau is Joseph Prud’homme who has succeeded: he is rich, considered, rewarded with the honors to which he was entitled, and willingly pompous. And this image is comically illustrated by the first scene of the novel, in which César Birotteau, in his nightgown, takes measurements of his apartment for the party he wants to give to mark its decoration, while his worried wife, in the same intimate outfit, gives him the timid performances of a good housewife. Balzac hadn’t seen his character and his subject at first sight. He had conceived his novel when he was writing Eugénie Grandet, in August-September 1833. There’s a bankruptcy in Eugénie Grandet, that of the old winegrower’s brother, who’s behind the action. M. René Guise believes that it was the idea of this bankruptcy that gave Balzac the idea of telling another, quite opposite story. In any case, what Balzac says about his project in a letter to Madame Hanska dated April 10, 1834, points to a very different path from the novel we can read today. He’s the country doctor, but in Paris,” announces Balzac, “he’s Socrates the fool, drinking his hemlock drop by drop in the shadows, the trampled angel, the unrecognized great man. Ah! it’s a great picture…”. This image of the righteous, misunderstood, “trampled underfoot” man Balzac compares to Doctor Bénassis, the benefactor who transforms a deprived canton in Savoie, has nothing in common with the far less apostolic destiny of the good Caesar Birotteau. The novel did not take on its current meaning until a year later, in September 1834. It was at this date that Balzac’s manuscript, the various versions of which have been collected, included new chapter titles: Rehabilitation and Emotion, which correspond to the current version. In addition, a new epigraph replaces the one Balzac had originally placed at the head. Taken from Etudes philosophiques, it alludes to the “lightning strikes” that can occur under the action of certain obsessive thoughts, through the action of “some moral acid suddenly poured over the inner being”.

César Birotteau

Although the outline of the novel was already sketched out in Balzac’s mind in 1834, it would be another three years before the project was realized. Periodic allusions appear in letters to Madame Hanska. But events pushed him into the background: a stay in Vienna with Madame Hanska in 1835, then the following year, the adventure of the Chronique de Paris was a financial disaster for Balzac, followed by another catastrophe, the bankruptcy of his publisher Werdet. César Birotteau ‘s project did not reappear until July 1837. At this point, Balzac has just signed a well-timed contract. The new management of Le Figaro bought two novels from him: Les Artistes, which never saw the light of day, and César Birotteau, both of which were due for serial publication at the end of the year. It was at this date that the writing of César Birotteau began in earnest, and it was a tricky one, as the novel had to go through several avatars. Initially prepared for serial publication, it had to be significantly enlarged following a change of printer who used a smaller typeface; then, the management of the Figaro changed its destination: it was no longer a soap opera to be offered to subscribers, but a supplement to be presented in weekly deliveries, and finally it would no longer be a supplement debited in installments, but a volume to be offered as a bonus. These trials and tribulations, each time altering the length and layout of the work, forced Balzac to work hard at fine-tuning, filling in and tidying up under the pressure of an imperative schedule. The management of Le Figaro offered twenty thousand francs if the novel was ready by December 10, 1837. This condition demanded, Balzac writes, intensive work lasting “twenty-five nights and twenty-five days”. This draft of César Birotteau is an edifying document on the working conditions imposed on Balzac. He described this period to Madame Hanska as “a tour de force”. René Guise, who studied the various phases of the writing process in the manuscript and proofs preserved in the Lovenjoul collection, rightly writes: “Balzac’s real ‘tour de force’ in writing this novel was not to have completed it in twenty days or so, but rather, under impossible conditions, to have produced text without disfiguring the work. “The history of La Comédie Humaine includes other similar “tours de force”.

A. Popinot

Nine years later, in 1846, Balzac himself wrote in a public letter to the critic Hippolyte Castille: “I have kept César Birotteau for six years (that’s a bit of an exaggeration) in draft form, despairing of ever being able to interest anyone in the figure of a rather silly, rather mediocre shopkeeper whose misfortunes are vulgar, symbolizing what we laugh at so much, small Parisian businesses. Well, sir, on a happy day, I said to myself: we must transfigure him by making him the image of probity. And it seemed possible.” Indeed, this is the true meaning of César Birotteau. The character embodies an idea, a feeling that is his life: this is the dramatic and philosophical meaning of the work. At the same time, the novel’s descriptive meaning is that it describes an economic environment and evolution. To fully understand César Birotteau, we must remember that this novel was originally intended to take its place among the Etudes philosophiques. For Balzac, these Philosophical studies are a series of works, novels and short stories, parallel to the descriptive 19th-century character studies In this series, Balzac’s intention was to set out, by means of examples, his ideas on the nervous organization of the human being, which, in his view, explained feelings, passions and the extraordinary actions performed under their influence. In the same year that César Birotteau, In 1839, Balzac had begun writing a very curious story, Martyrs ignored, which was never published in his lifetime and is not part of the The Human Comedy which illustrates some of his ideas on the subject. Under this title, Balzac reports on a conversation between a few intellectuals who have reflected, observed, and described some significant cases on the deadly effects of violent emotions. They conclude, “A yes or a no, in some cases, is like a pistol shot to the heart.” This word foreshadows the phrase used by Balzac to sum up César Birotteau‘s destiny in a nutshell. He is killed by the idea-probity as by a pistol shot. And it’s explained by the epigraph Balzac had first chosen for his novel: “Does not the soul compose terrible poisons by the rapid concentration of its enjoyments, its forces or its ideas: do not many men perish under the lightning strike of some moral acid suddenly poured into their whole inner being?” For Birotteau, probity lies at the very heart of his sensibility. His life was hard-working and naive. In this, he is the opposite of the cynics we see triumphing in La Comédie humaine. He admires government, bourgeois royalty, authorities. He is proud of his honesty and the honors it has earned him. He lives in an imaginary fortress he believes to be impregnable, protected on all sides by the esteem he has earned for himself, by the loyalty of those he loves, by the reliability of his notary. And when this edifice, which is his life, collapses, it’s like a storm that descends upon him, a tornado that destroys him. There’s nothing left, not only of his fortune, but of himself, since everything that made him confident and strong has suddenly disappeared.

Ragon, perfumer

It was at this point that he developed a monstrous obsession with probity all the same. He clings desperately to the only lifeline he has left, the idea of giving an image of himself in his misfortune, through his misfortune, thanks to his total probity. He set himself the task of regaining, through his courage, his selflessness, his rigorous determination to fulfill all his obligations in an exemplary fashion, the esteem and honor he thought he had lost. But then he builds an expectation within himself, he nurtures a dream, he feeds it with his sacrifices. And this dream, this fixed idea, as absolute in him as Père Goriot ‘s love for his daughters, he turns into an accumulation of hope and joy, a current of hope in which all his forces are engaged. In this way, he creates a lethal voltage for the day of his triumph. And he dies of the too-perfect, too-solemn realization of everything he had dreamed of: struck by lightning because the same day brings him too much intoxication with faith, his rehabilitation, his Legion of Honor, the praise of the public prosecutor, the congratulations of the Stock Exchange, and the return to his apartment of yesteryear, the resurrection of the old Birotteau, as complete, as perfect as if nothing had happened. He dies of the weight of this triumph. And the last scene is typical of Balzac’s dramaturgy, because it is a reconstitution. Birotteau’s family and friends have reproduced, for the day of his rehabilitation, the very decor of the famous ball that had been Birotteau’s triumph: same extras, same furniture, same hangings, same party. Balzac had already used this emotionally-charged re-enactment a few years earlier in the denouement of one of his short stories, Farewell. In order to cure a madwoman, the dramatic scene in which her madness had broken out – the death of her husband at the Berezina – had practically been reconstructed. And the staging had been so perfect that the madwoman had suddenly come to her senses, her reason had been restored, but with such violence that she had died like Birotteau, struck by lightning. The ending of César Birotteau is a repetition of the ending ofAdieu. The study of manners in César Birotteau is no less significant. By setting this scene in 1824, Balzac chose a transitional period in the history of Parisian commerce. The store of M. Guillaume, a drapery merchant in the rue Saint-Denis, described in La Maison du Chat-qui-pelote , gives an idea of trade as it existed under the Empire, continuing the mores of the profession under the reign of King Louis XVI. For merchants, the years following the defeat at Waterloo marked the end of the continental blockade, followed by a period of commercial activity during the foreign occupation and the first years of peace. This Paris shopping center had moved west. The area around Place Vendôme and Rue Saint-Honoré, home to César Birotteau’s beautiful store, had dethroned the area around Rue Saint-Denis. The very character of the business had changed. M. Guillaume was a merchant, César Birotteau is a trader. No longer just the owner of a well-placed perfume store catering to a wealthy clientele, he expanded his business, launching new products that he manufactured in his workshops and for which he was the exclusive distributor: La Double Pâte des Sultanes, L’Eau Carminative. He has representatives, he’s almost an industrialist. But the financial system has not kept pace with this transformation of retailers. Bankers are still sticking to the old mechanisms, essentially discounting bills in circulation. No bank exists to support the new ventures in which retailers engage. It was only in 1834, during the writing of César Birotteau, that banker Laffitte created the Caisse générale du Commerce et de l’Industrie, the forerunner of the merchant banks. Could this new organism have given Balzac an idea, or is it just a coincidence? Clearly, if such a bank had existed in César Birotteau‘s day, his bankruptcy would have been impossible, and he would have found the financing he sought in vain. Birotteau is as much the victim of a flaw in the banking system as of his own carelessness. For he was imprudent: that’s his tragedy. The grand ball he gave to celebrate his decoration, and the costly embellishments to his apartment, put him in difficulty, and this “impasse” was exacerbated by the flight of the notary with whom he had deposited the funds at his disposal. But the real cause of his disaster was that he was ahead of his time, while the bankers were behind. He wanted to take advantage of an “opportunity” and speculated on the land being developed around the new Madeleine church. This speculation, excellent in itself, was twenty years ahead of its time. Birotteau, who grew rich methodically, mechanically, according to the customs of his trade, is a victim of the new ways of getting rich, which he does not know, whose dangers he does not foresee, and of which he will be a victim like many others, like all those whose misfortunes Balzac describes at the same time in The Nucingen House. For La Maison Nucingen, the “twin work” of César Birotteau, as Balzac calls it, was in fact written in the same year as César Birotteau, during the laborious drafting of the novel’s manuscript. And it’s in La Maison Nucingen that we find the lesson that ties in with and explains the failure of César Birotteau. For La Maison Nucingen describes the arrival of a new element in the history of fortunes, the growth of fortunes through assets that do not yet exist and are represented only by paper. It’s the opposite of what made César Birotteau ‘s perfume house so strong and solid. Real estate fortune is a fortune of earthly essence, and has moved to rue Saint-Denis, an earthly image of hard work and stubbornness. For Birotteau’s work and his fortune are, like his life itself, the work and fortune of a Parisian peasant. On the contrary, his speculation on the Madeleine housing estates, in which he sunk his fortune, was an idea that did not originate with him, that was not in his temperament, an idea that he had never considered. foreigners. There was a wisdom of Birotteau, inscribed not only in his accuracy and prudence as a merchant, but in his very morals and thoughts, the morals and thoughts of a shopkeeper, a small saver, a good citizen. And it is the abandonment of this wisdom that is Birotteau’s undoing. This meaning is what gives César Birotteau an emotional quality that the subject hardly contained. Because behind Birotteau, with Birotteau, there’s a camp of good people who have the same ideas about life, work and probity as he does. Birotteau is not alone on the road to martyrdom. He is accompanied by those who share his faith, understand his sacrifice and join in. They follow him like disciples, following in his footsteps in times of trial and crossing the moors of misfortune with him, with a courage and serenity sustained by their whole lives, which, at that moment, bear witness for them. This ancient honesty When Birotteau leaves his house, his wife gives up her jewelry, he gives up his watch and gold earrings, their scruples afterwards to pay it all back, their ant-like stubbornness to rebuild everything, this participation by all without subterfuge or regret, this is what gives Birotteau’s catastrophe a kind of grandeur and moves the reader’s sympathy and admiration with these archaic images of a virtue that was part of the treasures of yesteryear. Source analysis: Preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (tome XIII) published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

The Story César Birotteau, a perfumer enriched by the success of his discoveries, and about to be awarded the Légion d’honneur, decides to transform his bourgeois home into a veritable palace to host a ball at the end of 1818 to mark the withdrawal of the occupying troops from France. His lavish spending, which frightened his wife and loyal employee Anselme Popinot (secretly in love with Mademoiselle Birotteau), gave him a dizzying ambition that led him to risk his entire fortune. Notary Maître Roguin senses Birotteau as a potential dupe, and draws him into a property speculation deal in the Madeleine district of Paris. Birotteau is in need of money, as the conversion work on his house and the new lifestyle he wants to lead there have seriously depleted his assets.

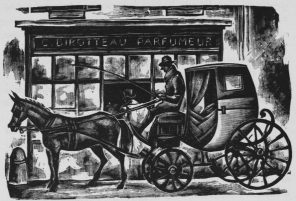

César Birotteau’s perfumery

In a clever double move, the swindling notary embezzles all the perfumer’s savings without giving him a receipt, before disappearing. The instigator of the plot against Birotteau is one of his former employees dismissed for theft: du Tillet, now admitted to the upper echelons of the Bank, who completes his revenge by undermining his former boss’s credit with the banks. Without the possibility of a loan, the perfumer couldn’t get by, despite the devotion of his uncle Pillerault, his wife and his daughter. He was forced to sell his store La Reine des roses to the clerk who had replaced Anselme Popinot: Célestin Crevel. But Anselme Popinot, who now runs a branch, will save him. With the help of the genial salesman Félix Gaudissart, he perfected and marketed an oil of his own invention, which, like Birotteau’s discoveries, became all the rage. Popinot spends days and nights secretly making hazelnut oil, with the profits going to César Birotteau. Helped by six thousand francs offered by Louis XVIII to the loyal royalist, Birotteau repaid all his creditors, was finally rehabilitated in 1823 and regained his Legion of Honor. But struck down by the battle, he died on the day of his triumph, leaving his prosperous business and the dignity of his name to his daughter and the faithful Popinot. Source story : Wikipedia

The characters César Birotteau: born in 1779, César was a famous perfumer in Paris. He was the son of Jean Birotteau, a captain killed in 1799. Madame César: Constance Pillerault, born in 1782, with daughter Césarine, who married Anselme Popinot. Césarine Birotteau: daughter of César and Constance Birotteau – born in 1801. Anselme Popinot: born in 1797, Birotteau’s clerk, druggist, Minister of Commerce, Count and Peer of France, “one of the most influential statesmen of the dynasty”. In 1823, he married Césarine Birotteau. Ragon parfumeur : Perfumer born in 1748. Marries a Popinot, sister of the magistrate and Anselme’s aunt.

Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

No Comments