Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans – Episodes 2 & 3

LA COMEDIE HUMAINE – Honoré de Balzac XIe et XIIe volumes des œuvres complètes de H. DE BALZAC by Veuve André HOUSSIAUX, éditeur, Hébert et Cie, Successeurs, 7, rue Perronet, 7 – Paris (1877)

Scenes from Parisian life

Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans – Episodes 2 & 3

December 1847 HOW MUCH LOVE RETURNS TO OLDER PEOPLE (episode 2) WHERE BAD PATHS LEAD (episode 3)

Analysis and history Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans – Episodes 2 & 3 is the best-known and only finished of Balzac’s blockbusters, which he set in motion in the 1840s. The list of these “novels with a hundred characters” that now cluttered his work schedule includes Les Paysans, Les petits bourgeois and Le député d’Arcis, a list that may well be incomplete. These “great machines” of fiction were delivered to the public in the form of separate novels, each bearing a title that later disappeared from the list of titles on sale: today, they are known by the general title under which they were brought together: this was the case for the three novels that make up Illusions perdues: that’s what happened to the four novels that make up Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans – Episodes 2 & 3. This last title brings together four novels published over a ten-year period, from 1838 to 1848. Here are their titles, which have now become those of the four parts of Splendors and miseries of courtesans: How girls like itpublished twice, in 1838 and 1843; How much love goes to old people, was also published twice, in 1843 and 1844; Where the wrong paths lead, published in 1846; and Vautrin’s latest incarnation, published in 1847. These “soap opera” titles already indicate the character of the work, which the general title makes less obvious. The first of these four novels, Comment aiment les filles, was published separately in this collection. In reality, it’s just a prelude. The dramatic situation is set out and developed in the next three novels, collected in Volume XIV of La Comédie Humaine, published by France Loisirs in 1985. The action, seemingly complicated and convoluted, can be summed up in a fairly simple diagram: The escaped convict Jacques Collin, better known by his false name of Vautrin, introduces himself as a Spanish priest on a secret diplomatic mission, Abbé Carlos Herrera. On the road near Angoulême, he took in Lucien de Rubempré when the latter wanted to commit suicide out of despair, following the catastrophes recounted in Lost Illusions (Part1). He makes it his instrument and his accomplice. He set out to establish Lucien on a high lifestyle, using his name to introduce him to the most elegant and exclusive society, proposing a grand marriage to a daughter of one of the most illustrious families in the nobility: to support this plan, Carlos gave Lucien a ravishing mistress, trained by him, for whom the wealthy banker Nucingen was seized with an invincible passion. You get a lot of money out of the banker, who ends up distrusting you. It’s aimed at a group that occasionally does private policing. The novel recounts the duel between these “privateers”, as they say in American crime novels, and the “gang” of accomplices of the false abbot.

Houssiaux

The second and third parts of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes follow the twists and turns of this duel and its tragic outcome. The final section brings Vautrin’s turbulent destiny to a close. This extraordinary plot is enough to set Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes apart from the rest of Balzac’s work. In an ingenious preface, Balzac tries to persuade us that this excursion into the murky underworld of Parisian life was indispensable to his picture of manners. It’s a pretext that doesn’t impose much. Although the situation imagined by Balzac in 1838 predates the Mysteries of Paris by Eugène Sue, which began publication in 1842, we can’t help but notice between The mysteries of Paris and Splendors and miseries of courtesans a kinship of novelistic excess that makes Balzac’s novels of manners drift towards an exceptionality that is generally foreign. Balzac’s readers outside France seem to have felt the same way, since Balzac’s penetration abroad, much slower than one might imagine, has never made any room for Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, which is only accessible in translations of the entire La Comédie humaine . Despite this marginal position, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes is nonetheless regarded as one of Balzac’s great novels, one of his most pathetic and, in some respects, one of his most significant. Oscar Wilde confessed that the death of Lucien de Rubempré, which ends the novel, had been “the greatest sorrow of his life”. Albert Thibaudet so fearlessly admired the character Balzac had portrayed as Vautrin and Carlos Herrera that he equaled him with Baron de Charlus in La Recherche du temps perdu, regarding them both as the most powerful novelistic creations of the 20th century. This praise is not unanimous. Critics prior to 1914 were embarrassed. School publishers are just as reluctant as foreign audiences. It is significant that in his excellent collection of Morceaux choisis de Balzac, prepared in 1914 and published in 1927, Joachim Merlant omits such a considerable work. André Bellessort, in his study of Balzac published in 1925, was the first academic critic to cautiously join forces with the writers. He devotes few pages to Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes , but he wrote of Vautrin that Balzac “could be proud of having given the mud with which he kneaded it, the lustre and solidity of bronze.” Even today, moralism and pusillanimity weigh heavily on this powerful work, which does not occupy its rightful place in the official presentation of Balzac’s oeuvre. Certainly, the implausibility of the situation and Balzac’s casual invention of twists and turns may justify hesitation. The most serious of these implausibilities is that which the reader is entitled to object to Vautrin’s plan, which underpins the entire plot. It’s all too clear that no family occupying the rank of the de Grandlieu family will agree to give one of its daughters to a newcomer whose situation is unclear without obtaining information about his family and his fortune. From then on, by engaging in this absurd game, Vautrin, the profound Vautrin, himself draws the attention of the official and private police to his affairs, and sets fire to his own house.

Vautrin

On the other hand, Rubempré’s failure at the Grandlieu house, which shows the childishness of Vautrin’s calculations, is not at the root of the detective story. Vautrin’s mystery surrounding Esther’s existence leads to Nucingen’s investigation. And it’s not even Esther’s suicide that triggers the irreversible tragedy, but a superfluous circumstance: the disappearance of the 750,000 francs from the annuity offered by Nucingen. The plot is thus skilfully constructed to persuade the reader that Vautrin is the victim of an unforeseeable double misfortune, Esther’s suicide and the robbery that accompanies it. The result of this skilful montage is to conceal Vautrin’s false calculation, which casts doubt on its depth, and to fix the reader’s attention on the fatality that destroys such a skilfully combined enlistment operation. The duel that ensues between Vautrin and the policeman who has identified him in his disguise as a Spanish priest leads to a series of extraordinary events that have nothing to do with the study of manners, but are all part of the “detective story”. The sequence of events is logical, implacable and exciting, but Vautrin’s hopeless situation reduces him to a conventional game between reader and novelist. For those who accept this fundamental convention of the “detective novel”, the duel between Vautrin and Corentin is dramatic, moving, full of human resonance, and we can say with Oscar Wilde that Rubempré’s death, at the very moment when an unforeseen event brings him wealth and freedom, is an event as sad, as distressing, as the denouement of a real drama we might have known. But for those who reject this convention and read Balzac’s novel without complacency, there’s no decision by the two adversaries that doesn’t make you smile, no episode that isn’t absurd, no denouement, however pitiful, that doesn’t succeed in truly provoking emotion. With Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, as with Ferragus, we enter a special zone of Balzacian invention, where the reader can only follow the novelist by agreeing to put his or her critical mind on hold. This inferior quality of invention does not owe as much as one might think to the influences Balzac underwent in his youth, and to the mechanisms he developed at that time, which can be seen in some of his novels. Nor can it be explained by the imitation of Eugène Sue or Frédéric Soulié, who produced substantially different works: rather, it is due to an intrinsic disposition in Balzac’s imagination, a kind of excessive credibility on the part of the author with regard to the events he invents, explained both by his enthusiasm as a creator and by a certain judgment. a priori on some of the mysterious careers of Parisian life. Digressions, descriptions and analyses, which are so abundant in Balzac’s novels, are few and far between in this central part of the novel: everything here is peripatetic, and Vautrin is a general leading a battle. It’s in the parts that prepare the action or bring it to a conclusion, i.e. the first, third and fourth parts, that Balzac once again becomes the historian of his time, or explains the exceptional characters he describes. The last two novels in this series, Où mènent les mauvais chemins and La dernière incarnation de Vautrin – today, the last two parts of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes – are an example of Balzac’s plasticity. Then we find another Balzac. It’s all over, Vautrin has lost. But within the dark walls of the old Conciergerie, another drama begins, not a violent one, but a devious one, unfolding in the shadows. Of course, there are still too many accomplices, too many disguises, too many secret messages, too many subterfuges, but we forget that these are just jolts. All we can think of is the terrible machinery that operates in silence, in a lantern-light glow: the so-called justice system. Unadulterated reality is so powerful, so crushing, that it’s the only thing you can feel. The description of the judicial mechanism, scarcely changed in our time, the overpowering sovereignty of the examining magistrate, the annulment of the victim who has become a sub-being referred to as the accused, the defendant, the accused, the names of insects, the isolation, the dungeons, the guards: all of a sudden, we enter an underground world that Balzac makes more fearsome than the bloody soap opera that preceded it. These justice officials , described by Balzac, so simple and so real, are frightening. Its pallid, pudgy examining magistrate, both corruptible and retaining a small, imbecilic corner of professional conscience whose autonomous operation leads to disaster, its immobile, despairing public prosecutor, wordlessly enduring the martyrdom of command, and the cynicism of these pages, this masterly blow to the majesty of Justice, this so true, so implacable dismantling of the judicial comedy, one realizes, only on reflection, that it supports and confirms the dismantling of human hypocrisy that is Balzac’s entire work. Because of this reinforcement, which comes from elsewhere, from all the truth that Balzac’s work contains, this ending is vigorous, simple and admirable, – although it is doubtful that this episode aroused the enthusiasm of the legal world as much as Balzac says.

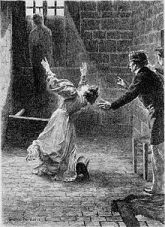

Esther staggers before Lucien’s body

The drama here is pathetic, precisely because it excludes all violence: it’s the small, almost impalpable facts, the imperceptible copper strips on the scales that tip the scales of fate. An immense stake, a beloved being, and even, because of the unknown will that enriches Esther, the victory so vainly sought and so close at hand, all depend on this fetu. Amazing suspense, achieved almost without means. Rubempré’s death was simply the story of a blunder. All that was needed was for the juge d’instruction, as we had tried to make him understand, not to question Lucien. A scruple held him back. Professional conscience, habit, a little perversity on the part of a tormentor, a captious phrase, trigger the avalanche. All is lost at the drop of a hat: not even a premeditated manoeuvre, just a coincidence. Perhaps it’s these simple means, this cruelty of fate so real, untimely and absurd, that most moves the reader. It’s not just this return to truth and the drama of truth that makes the ending of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes so admirable. It’s also because then, and only then, do we understand the truth of the characters. We already had some idea of this in the first part. The character of Esther, too often explained by reference to the Romantic rehabilitation of the courtesan, is in reality, for Balzac, a case in point. physiological which explains both the intensity of passions in the milieu of the “insoumis” (the title says it all: How girls like it) and also the abnormal lives that the same dispositions bring to their lovers. The existence of a “submissive girl” implies sentimental frustration. For some – and this is the case for Esther – total love, uniting physical adoration and the invasion of the soul by an absolute, never-before-experienced feeling, produces a mobilization of all forces, because this love acts in a vacuum. This metamorphosis, this blossoming that a single, gradually-encrusting feeling produced in Eugénie Grandet or Rosalie de Watteville fromAlbert SavarusIn a single moment, all at once, in the soul of Esther, who could not be distracted by any affection, any love, any sentimental roots, and who was experiencing for the first time the shock of these two feelings. She is vowed, she is a slave, she belongs for her whole life to the one who caused her to be born again.

Esther dying

It’s also a physiological explanation for the abnormal existences of those who share their lives. Passion,” says Balzac, “is almost always, in these people, the primitive reason for their daring ventures, their assassinations. The excessive love that drives them, constitutionally, say the doctors, towards women, uses all the moral and physical strength of these energetic men. Hence the idleness that devours our days, for the excesses of love require both rest and restorative meals. Hence this hatred of all work, which forces these people to resort to quick ways of making money. If the Faculty of Medicine is to be believed, seven-tenths of all crimes are the result of these men’s disordered physical love. The proof, moreover, is always striking, palpable, at the autopsy of the executed man. So the adoration of their mistresses is earned by these monstrous lovers, the scarecrows of society”. It’s a theory by Esquirol, a great physiologist who was Balzac’s contemporary, but it’s also an application of Balzac’s theories in the Théorie de la Démarche de La Peau de chagrin. And this is, in any case, the philosophical explanation for the exorbitant lives he describes in his novel, and by this means links up with the general description of the forms that energy takes in social life. It’s also in this last section that Balzac explains, for the same physiological reasons, what he calls Vautrin’s “bronze nature”, which gives his character that strength and stature that all Balzac’s commentators have admired. But this explanation appeals to another side of Balzac’s physiology. Vautrin isn’t exhausted by extreme pleasures, he doesn’t need phases of rest to replenish his strength. He is a living example of the “concentration of energy” that enables great actions and swift decisions. With him, “the decision equaled the glance in rapidity, thought and action sprang like a single flash, the nerves hardened by three escapes, by three stays in the bagne had reached the metallic solidity of the nerves of the savage.” This “concentration of energy”, which in others is the secret of their power of thought or their terrible will, is projected into immediate action: it gives him his physical strength gathered entirely in one point and in one moment, and his instantaneous mastery of himself. On this terrain, far removed from Balzac’s usual examples, it’s an example of the Balzacian theory of the will. And it’s this same disposition that explains Vautrin’s sudden and seemingly inexplicable resignation after Lucien de Rubempré’s death. Iron, Balzac reminds us, yields to certain degrees of repeated beating or pressure. Blacksmiths then say that the iron is rusted; the iron bar disintegrates, the rail is deformed. Well, the human soul,” says Balzac, “or, if you like, the triple energy of body, heart and mind, finds itself in a situation analogous to that of iron, as a result of certain repeated shocks. It is then with men as with iron: they are rusted… The hardest hearts break then.” There is suddenly a “dissolution of energy”, says Balzac: “Napoleon experienced this dissolution of all human forces on the battlefield of Waterloo.” His system of Philosophical studies to understand the world of crime and create its imaginary hero.

Popinot

This “concentration of the will”, which explains Vautrin as it did Louis Lambert, is also a phenomenon that can occur temporarily under the effect of a passion that has reached its climax. Mme de Sérizy, a frail, blonde marquise and boudoir doll, ran screaming to the cell where her lover had hanged himself: clinging to the bars that closed the door, she shook them with such violence that her weak hands broke the wrought iron that was supposed to resist all the efforts of the condemned. The prison governor, shocked by this fact, likened it to a magnetism experiment in which a somnambulist had crushed his hand in the same way as a torture device. It seems to me,” he concludes, “that under the influence of passion, which is willpower gathered on one point and attained to incalculable quantities of force, as are all the different species of electric power, man can bring his entire vitality, either for attack or for resistance, into this or that of his organs. This little lady had, under the pressure of her despair, sent her vital power into her wrists.” It’s an example that Balzac could have added to this gallery of Martyrs ignorés, the unfinished essay in which he cited facts that illustrate the system he wanted to set out in full in his Essai sur les forces humaines, which he didn’t have time to write. This psychological reconstruction gave “Balzacian” significance to Balzac’s copious documentation on the underworld and prisons. His informants had been numerous. On prison regimes, we cite Benjamin Appert, a philanthropist who was one of the opponents of prison administration; on prostitution, Doctor Esquirol, founder of psychiatry, doctor at the Salpêtrière and then at the Charenton hospice, and Parent-Duchâtelet, both of whom had devoted studies to the issue; finally, a well-documented article by Arnould Frémy in Les Français peints par eux-mêmes ; sur la police, les Mémoires du préfet de police Desmarets, ceux de Peuchet, ancien archiviste de la police et un ouvrage de Froment, La police dévoiléeGlandaz, one of Balzac’s fellow students at Vendôme, who became a public prosecutor in Paris; the public prosecutor at Bourges, Mater, whom Balzac often met when he was writing his novel; Me Guyonnet-Merville, the solicitor with whom Balzac had once clerked and who had become a magistrate; and M. de Berny, also a magistrate. Balzac had even gone so far as to attend certain trials in order to gather information – the trial of young Donon, for example, where he learned that the defendants parked in the courtyard organized trial rehearsals among themselves. One of his most remarkable informants was probably Vidocq himself. The real Vidocq had been sentenced to the penal colony as a swindler and forger after an eventful life, and had twice escaped from the Nantes penal colony. In 1809, he himself suggested to Jean Henry, an official at the Préfecture de Police, that he set up a security brigade made up of former crooks to keep an eye on the Parisian underworld. After a few years in this department, he set up a private police agency, which began operations in 1822. A legend had grown up around his name, and Mémoires attributed to him were published at the end of the Restoration. He was a character with neither the stature, audacity nor picturesqueness of Vautrin. However, his wealth of experience could provide Balzac with valuable information. We know that Benjamin Appert, who knew him, organized a dinner party attended by Alexandre Dumas and Samson, the executioner of Paris, whose apocryphal memoirs Balzac had published in 1829. Was it their first meeting? One scholar, M. Jean Savant, believes that Balzac had met Vidocq several years before this date. In any case, he had heard of him, both from the authors of Vidocq’s pseudo-memoirs, with whom Balzac was acquainted, and from M. de Berny, who appears to have been in contact with him as a magistrate during his period of police service. Vidocq’s career obviously gave Balzac the idea for Vautrin’s “reversal”, which is the subject of the last part of his novel. But the real-life character is so far removed from the Vautrin of the novel that Balzac must be given full credit for his character. Here again, as in the first part of Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, creation through invention is far superior to copying the models her time could provide.

Vidocq alias Vautrin

The characters Lucien de Rubempré: Born in L’Houmeau, a small provincial town near Angoulême, Lucien Chardon – de Rubempré on his mother’s side – went to Paris to make his fortune as a writer. He is the author of two works: a collection of poetry entitled “Les Marguerites” and a novel, “L’Archer de Charles IX”, which he hopes will make him famous. (See Lost Illusions) His difficult beginnings in Paris – publishers’ indifference to his literary works pushed him towards journalism, where he shone for a time thanks to his literary talents. His boundless pride and vanity will lead him into reckless spending and debt. Ruined, he ruined his mistress, the young actress Coralie, who died as a result. He dragged down his mother, brother-in-law and sister, whom he also robbed. On the road back to Angoulême, in the most destitute and darkest of moods, he meets the Abbé Herrera (Vautrin), who takes advantage of the young man’s fragility and despair to make him his “thing” and serve his powerful interests. Carlos Hererra: Vautrin will use Lucien to obtain for him the status and honors he aspires to for this “adopted son”. He failed in his attempt to save his protégé from the clutches of the law, but through a combination of circumstances and timing, indirectly caused his death in the Conciergerie prison. With the suicide of his protégé, Vautrin loses all hope of fortune, and re-establishes himself by negotiating letters from three compromised noble families (Mme de Sérigny, Mme de Maufrigneuse, Clothilde de Grandlieu). He buys himself a good conduct by becoming a policeman. Esther: Esther is an eighteen-year-old prostitute when she meets Lucien de Rubempré. Born of the Belle Hollandaise’s passion for the notorious and avaricious usurer Gobseck, Esther is considered one of the most beautiful people in Paris. Secretly in love with Lucien de Rubempré, she sacrificed herself for the dandy’s love and died, exhausted from all the self-denial and sacrifices made for her lover, including seducing Baron de Nucingen to extract from the old banker the million needed for Lucien’s marriage and fortune. Asia: Vautrin’s aunt, matchmaker and toilet trader. She is the convict’s shadow and right-hand woman in all his mafia ventures. Entrusted by Vautrin (the false Abbé Herrera) with guarding and spying on Esther’s every move, she is hired by her nephew as Esther’s maid and cook. Europe: Hired by Vautrin as Esther’s maid. Like Asie, she will be the young woman’s watchdog, reporting to Vautrin any events that could jeopardize his plans for Lucien’s marriage. Clotilde de Grandlieu: Clotilde-Frédérique is the second of five daughters of the Duke and Duchess of Grandlieu (Clotilde’s mother is an Ajuda from the elder branch allied with the Bragances). Ugly and charmless, Clotilde was twenty-seven when she fell in love with Lucien. Very much in love with the young man, she will have a great influence on his parents, who do not look favorably on their daughter’s marriage to a “rôturier” whose fortune is unknown. Baron de Nucingen: A banking magnate whose immense fortune came from risky transactions carried out at the expense of a society weakened by the political events of the first half of the 19th century, namely the numerous revolutions that weakened France between 1790 and 1830. These were the beginnings of banking and the first stock market transactions – it was because these new financial techniques were not yet well known to the general public that Nucingen built his fortune by fleecing the petit bourgeois and merchants. Thirsty for power and money, Nucingen believes he can buy anything – even feelings. Madly in love with Esther, he will spend fortunes (extracted by Vautrin) to buy the courtesan’s love. He never gets it, and Esther poisons herself to escape both the terrible suffering caused by the loss of Lucien, who is about to get married, and the assiduity of the old banker she can’t stand.

1) Source analysis/history: Preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (tome XIV) published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

2) Source for character descriptions: Wikipedia.

No Comments