The Unknown Masterpiece

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XIVth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1874)

Philosophical studies

THE UNKNOWN MASTERPIECE

Dedicated work to A LORD

Analysis of the work This tale, first published in the magazine The Artist in August 1831, appeared in bookshops in September of the same year in the Philosophical novels and talesin a slightly different version, and in 1837 was reproduced in the Philosophical studies with significant additions and reworkings. These three states of text correspond to quite different meanings of the subject. The version published in L’Artiste is subtitled “conte fantastique”. It is divided into two stories, one entitled Maître Frenhofer, the other Catherine Lescaut. The subtitle of “fantastic tale” is an advertising ploy. Fantastic tales” were all the rage in 1831, following the success of Hoffmann’s Tales from Berlin. This reference was all the more legitimate as Balzac had been inspired by a tale by Hoffmann translated into French in 1828 under the title L’Archet du baron de B., and reproduced in April 1831 in the magazine L’Artiste, to which Balzac contributed, under the title La Leçon de violon. The two tales are parallel, with the difference that Hoffmann, who had had a musical career, features musicians, while Balzac shows painters. But the set-up, the characters and the meaning are the same. In Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu, Balzac imagines the youthful adventures of Nicolas Poussin, then a pupil of Porbus, and his meeting with the painter Frenhofer, the illustrious master to whom Jean de Mabuse entrusted the secrets of his art. Frenhofer hides an “unknown masterpiece” in his studio, a canvas he has painted using these secrets and which he shows to no one. Poussin, passionate about his art and eager to learn, offers the old Frenhofer his young mistress Gillette as a model. Frenhofer shows him the mysterious painting: it’s just a grimoire of colors that represents nothing, not a work of art, but a painter’s illusion. Poussin learns to defy the excesses of thought and imagination in art, but he loses his young mistress, who doesn’t forgive him for his deal. In Hoffmann’s tale, the illustrious violinist, Baron de B., is the custodian of the secrets of his art, just as Frenhofer is the protector of the beginner presented to him, finally revealing to his admirer the magic of his performance: all we hear is a cacophony that elicits the same cries of admiration from the Baron as Frenhofer’s when he shows his canvas. We fail to disabuse him, just as in the first version of Masterpiece Unknown, Frenhofer persists in his happy delusion. In both works, not only are the story phases the same, but the details correspond point by point. Pierre Laubriet, an excellent Balzacian, who devoted his secondary thesis to Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu, followed by Pierre G. Castex, considers this episode to be the main source of Balzac’s tale. Indeed, it was this hallucination that Balzac retained. But the structure of the tale follows the first model more exactly. There is, however, an important difference between these two tales and Balzac’s short story: the invention of the character of Gillette introduces a love plot to this “fantastic tale”, which does not exist in Hoffmann’s work. In the final version of Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu, aesthetic meditation takes up so much space that the little story of Nicolas Poussin and Gillette plays only a secondary role. But it’s curious to note that Balzac’s contemporaries read the first version of The Unknown Masterpiece. Balzac’s additions to the original version, first fragmentary in the 1831 bookshop edition, then much more extensive in the 1837 version, turned this love story into what Pierre Laubriet called “an aesthetic catechism”. The Viscount de Lovenjoul, who assembled the famous collection on which all specialists in Balzac’s work depend, attributed to Théophile Gautier the artistic theories that Balzac had Frenhofer express. He even thought that Théophile Gautier had collaborated on the 1837 version. Art critics, for their part, thought of Delacroix. It’s also interesting to note that, much later, Cézanne recognized his own ideas in Frenhofer’s speeches. This is not the least indication of the seriousness and interest of Balzac’s theses. It is not, however, the essence of Unknown masterpiece. Balzac is not only a doctrinaire of painting. Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu is also, and above all, an application of Balzac’s theses to the specific field of painting. In La Peau de chagrin, Balzac laid down the principle that was to be illustrated in Contes philosophiques. Félix Davin, in his Introduction to the Contes philosophiques summed it up as follows: “M. de Balzac considers thought to be the most vivid cause of man’s disorganization… The disorder and havoc wrought by intelligence in man considered as an individual and as a social being, such is the idea that M. de Balzac threw into his works.”

Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), 17th-century French painter

Frenhofer’s illusion is an example of this thought-induced disorganization. By dint of meditating on the essence of painting, i.e. on the means that enable the artist to achieve a total transposition, a magical transposition of reality, Frenhofer ended up forgetting that the painter is a craftsman: and as such, it’s not what he thinks that’s important, but what he does. Frenhofer’s meditation engages him in a process of translating reality that ultimately distances him from the reality he is dedicated to representing. The subtleties of making develop a stylistic obsession in him; he is no longer concerned with what he sees, but only with the expression through which he will show what he sees. This meditation led him towards a surrealism which, under the pretext of being the most profound translation of reality, substituted itself for reality and ultimately rendered it unrecognizable: it was translated according to the painter, but no longer so for the viewer. Meditation on painting leads to the destruction of painting, just as meditation on style leads to the destruction of language. This profound view, which foreshadows so many aesthetic problems of the twentieth century, is nothing other than a particular case of the destruction of creative power, the most complete example of which is given by Louis Lambert summed it up in a single word, “la pensée tuant le penseur” (“thought killing the thinker”), as Balzac put it in a letter to Madame Hanska in February 1839: “… I’m not a thinker, I’m a thinker. The Unknown Masterpiece shows the disorder that thought in all its development produces in the artist’s soul.”

Eve Hanska

Frans Porbus

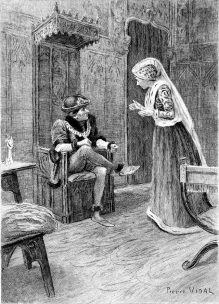

The story The young, still unknown Nicolas Poussin visits the painter Porbus in his studio. He is accompanied by the old master Frenhofer, who comments on the large painting Porbus has just completed. This is Marie l’Egyptienne, which Frenhofer praises but considers incomplete. With just a few brushstrokes, the old master transforms Porbus’s painting to such an extent that Mary the Egyptian seems reborn to life after his intervention. However, while Frenhofer mastered the technique perfectly, for his own masterpiece La Belle noiseuse, which he had been working on for ten years, he lacked the ideal art model, a woman who would inspire him to the perfection he was striving for but never attaining. This future masterpiece, which no one has yet seen, would be the portrait of Catherine Lescaut. Nicolas Poussin offers to pose the woman he loves, the beautiful Gillette, which Frenhofer accepts. Gillette’s beauty so inspired him that he finished La Belle noiseuse very quickly. But when Poussin and Porbus were invited to admire it, they could only make out a small part of a magnificent foot lost in an explosion of color. The disappointment on their faces drives the master to despair. The next day, Frenhofer died after setting fire to his workshop. Poussin loses Gillette, who can’t forgive him for using her, and puts the love of his art ahead of theirs.

Master Frenhofer

The characters Frenhofer: 17th-century painter Nicolas Poussin: A historical painter who inspired Balzac’s short story. His works are mainly religious and mythological compositions, with figures and animated landscapes. He was one of the greatest classical masters of French painting.

Midas and Bacchus – N. Poussin

Quiet time – Nicolas Poussin

Porbus:

Frans Pourbus or Porbus the Younger, (b. Antwerp, c. 1569-1570 – d. Paris, 1622). Flemish painter, inspiration for Balzac’s novel. He is the son of Frans Pourbus the Elder and the grandson of Pieter Pourbus. It was he who introduced the ceremonial portrait to France. Thanks to the exceptional quality of his portraits, he spread the Pourbus reputation throughout Europe. Among his outstanding works, These include the portrait of Henri IV (cuirassed), the large full-length portrait of Queen Marie de Médicis wearing the sumptuous fleur-de-lis gown worn at her coronation, another portrait of Marie de Médicis in black mourning clothes, and religious paintings such as Saint François receiving the stigmata and the Last Supper.

Marie de Médicis

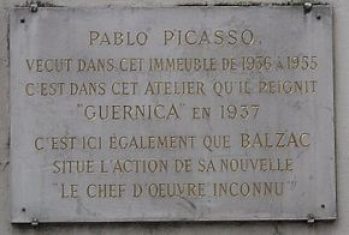

Commemorative plaque at 7, rue des Grands-Augustins

The story, featuring the old painter Frenhofer, allowed Picasso, who was fascinated by the text, to identify all the more easily with it, since Frenhofer’s studio was not far from Porbus’s, on rue des Grands-Augustins. In 1931, Ambroise Vollard asked Picasso to illustrate The Unknown Masterpiece. Shortly after Vollard’s proposal, Picasso rented a studio at number 7 on the same street, where he painted his masterpiece, Guernica. Picasso remained in this studio throughout the Second World War. Gillette: Nicolas Poussin’s 17th-century mistress.

Source analysis: Preface from the 23rd volume of La Comédie Humaine, published by France Loisirs in 1987, based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris. The information gathered in the genealogy of the characters comes from Wikipedia and the work of Félicien Marceau (Balzac et son monde – Gallimard). The story and arguments reported are taken from the pages of the universal encyclopedia Wikipedia.

No Comments