The Quest of the Absolute

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XIVth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1874)

Philosophical studies

Balthazar Claës and his daughter Marguerite

THE QUEST FOR THE ABSOLUTE

Dedicated work TO MADAME JOSEPHINE DELANNOY NEE DOUMERC Madam, may God grant that this work has a longer life than mine; the gratitude I have devoted to you, which I hope will equal your almost maternal affection for me, would then last beyond the term set for our feelings. This sublime privilege of extending the existence of the heart through the life of our works would be enough, if there were ever any certainty in this regard, to console all the pains it costs those whose ambition it is to conquer it. So I’ll say it again: God willing!

De Balzac. La Recherche de l’Absolu is a novel that first appeared in 1834 in volume 3 of Etudes de Moeurs, Scènes de la vie privée, then frequently reworked by the author, it was published in a shortened version of 40 pages, with a dedication to Joséphine Delannoy in 1839. Finally, in its third version (1845), it was placed in the Philosophical Studies section of La Comédie Humaine.

Balthazar

Analysis of the work This is one of the novels that established Balzac’s reputation. It appeared in October 1834, after Eugénie Grandet from the previous year and before Le Père Goriot, published a few months later. This date is important because it marks a decisive moment in the conception and organization of Balzac’s work. This is what gives La Recherche de l’absolu a historical importance independent of its own value. At this date, Balzac, who was always concerned with the unity of his work, presented his entire output in two distinct sets. An initial “subdivision”, starting with Scènes de la vie de province and Scènes de la vie parisienne, forms a block to which Balzac has just given the general titleEtudes de mœurs au XIXème siècle. It’s a descriptive series. At the same time, other short stories, corresponding to a different preoccupation, were grouped together under the title of Romans et contes philosophiques. This second series, based on La Peau de chagrin, appears to have no connection with the first: it even has a different publisher. At the time, Balzac was not yet thinking of La Comédie humaine, nor had he invented the return of the characters. The Search for the Absolute is the first work to bridge the gap between these two series: it is both a descriptive work that can be placed among the Scenes from private life than among Scenes from provincial life and a “philosophical” work that illustrates the “ravages of thought” thesis of the Philosophical novels and tales. Balzac discovered that his descriptive works could be nourished by these philosophical theses. It’s a momentous discovery, not only because it gives unity to the scattered works produced up until then, but because it gives a profound unity to Balzac’s entire oeuvre, by basing it on a certain definition of man and a certain explanation of the passions. In this respect, La Recherche de l’absolu is a true demonstration. Balzac takes as an example the historic Claës family, famous in Flanders, a historic fortune, both symbolized by an old-fashioned mansion where the treasures of five or six generations are accumulated. Morally, it’s also solid: a respected father, exemplary conjugal love, a patriarchal life. It all seems indestructible. All this will be destroyed, however: not by misfortune, not by violence, not by passions or insubordination, but simply by a idea that grows in the father’s brain, that becomes a obsessionIt’s an all-consuming idea that will unravel this bundle of forces so solidly bound together, that will eat away at it, spread like wildfire and finally destroy what seemed out of reach. This pattern of destruction, developed with didactic rigor in La Recherche de l’absolu, is only reproduced in all its purity in La Cousine Bette and La Rabouilleuse. But instilled in different forms and in more or less diluted doses, attributed sometimes to a passion, sometimes to an illusion, most often to the pressure of vanity, ambitions and greed that civilization overexcites, these all-consuming, implacable feelings that take hold of a being will lead in most of Balzac’s works to the same destruction of zones of happiness that seemed solid and well protected.  This demonstration of the power of the idea is one of Balzac’s most impressive novels, but admittedly also one of his least plausible. It was a seemingly unimportant incident that led to this collapse: a conversation with a Polish officer passing through the Claës’ home. This officer had studied chemistry but had to give it up, and he explained his conclusions to Balthazar Claës, who was also passionate about chemistry. Each of them is convinced that all bodies encountered in nature are derivatives of a single, indissociable substance, theAbsoluwhich produces all other bodies by various combinations, under the effect of a power analogous to electricity; in reality, Balzac does not pronounce the word, of course, under the effect of electricity. radiation. It’s easy to see why Balzac can so easily imagine Balthazar Claës’ reasoning and the prospects of this discovery. L’Absolu reproduces in the inorganic the system of thecomposition unit which was Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s thesis to explain animal creation from a single living essence diversified into thousands of species, a thesis that Balzac had not only adopted enthusiastically, but had himself made the basis of his system of social zoology. At the same time, Balzac recognized in this unknown material element, which allowed for a transmutation of organic matter, his own conception of the world. materiality of thought in which he saw a kind of fluid: so the mysterious cause of certain inexplicable phenomena of human energy could also be the cause of the complexity of inorganic substances. La Recherche de l’absolu is therefore a science-fiction novel for both Balzac and Balthazar Claës: and it’s easy to see how Balzac can imagine the enthusiasm that this unitary conception can provoke: it is the secret of all creation. Raymond Abellio, in a preface he wrote for a paperback collection, clearly saw this particular aspect of La Recherche de l’absolu. It would have been even more obvious to him had he been able to relate it to Balzac’s general conception. The difficulty for the novelist was to transcribe this idea into the language of chemistry: and not only into this language, but into the work of contemporary chemists.

This demonstration of the power of the idea is one of Balzac’s most impressive novels, but admittedly also one of his least plausible. It was a seemingly unimportant incident that led to this collapse: a conversation with a Polish officer passing through the Claës’ home. This officer had studied chemistry but had to give it up, and he explained his conclusions to Balthazar Claës, who was also passionate about chemistry. Each of them is convinced that all bodies encountered in nature are derivatives of a single, indissociable substance, theAbsoluwhich produces all other bodies by various combinations, under the effect of a power analogous to electricity; in reality, Balzac does not pronounce the word, of course, under the effect of electricity. radiation. It’s easy to see why Balzac can so easily imagine Balthazar Claës’ reasoning and the prospects of this discovery. L’Absolu reproduces in the inorganic the system of thecomposition unit which was Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s thesis to explain animal creation from a single living essence diversified into thousands of species, a thesis that Balzac had not only adopted enthusiastically, but had himself made the basis of his system of social zoology. At the same time, Balzac recognized in this unknown material element, which allowed for a transmutation of organic matter, his own conception of the world. materiality of thought in which he saw a kind of fluid: so the mysterious cause of certain inexplicable phenomena of human energy could also be the cause of the complexity of inorganic substances. La Recherche de l’absolu is therefore a science-fiction novel for both Balzac and Balthazar Claës: and it’s easy to see how Balzac can imagine the enthusiasm that this unitary conception can provoke: it is the secret of all creation. Raymond Abellio, in a preface he wrote for a paperback collection, clearly saw this particular aspect of La Recherche de l’absolu. It would have been even more obvious to him had he been able to relate it to Balzac’s general conception. The difficulty for the novelist was to transcribe this idea into the language of chemistry: and not only into this language, but into the work of contemporary chemists.

Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, French naturalist (1772-1844)

This transcription required a great deal of documentation, which a remarkable thesis by one of Balzac’s leading specialists, Mme Ambrière-Fargeaud, has enabled us to reconstruct. This research has shown that influences that were mentioned in the past, such as Sainte-Beuve’sHermès dévoilé by Cyliani, or Balzac’s project on Bernard Palissy, listed in his Album under the title Les Souffrances de l’inventeur, should be regarded as very secondary. Balzac’s meeting with the Polish mathematician Hoené Wronski, mentioned in a letter to Madame Hanska dated 1er August 1834, does not seem to be decisive: Balzac seems to have remembered Wronski only because of a famous swindle trial that had taken place in 1818 concerning the sale of the secret of “l’absolu” to a naive sponsor. On the contrary, Ms. Ambrière-Fargeaud’s research clearly shows the itinerary of Balzac’s documentation. Two members of the Académie des Sciences taught me chemistry,” he told Madame Hanska in a letter of October 1834, “to keep the book scientifically true. They made me rework my proofs up to ten or twelve times.” Balzac’s two tutors were two of his neighbors, François Arago, director of the Observatoire, which was just a stone’s throw from the rue Cassini where Balzac lived, and a collaborator and friend of François Arago, Ernest Laugier, who was still very young. François Arago had probably come into contact with Balzac through his brother Etienne Arago, who had been one of Balzac’s collaborators when he was writing L’Héritière de Birague. Balzac’s two initiators got him to read the treatise on chemistry just published by one of the masters of modern chemistry, the Swedish Jean-Jacques Berzelius. It was from this treatise that some of Balthazar Claës’s experiments quoted by Balzac originated.

Jean-Jacques Berzélius (1779-1848)

Mme Ambrière-Fargeaud suggested adding to these two names that of the great English chemist Humphry Davy and William Prout: the work of these two scientists had been explained to Balzac by a friend of François Arago, Jean-Baptiste Dumas, a contemporary of Balzac who had just been elected to the Académie des Sciences and who introduced some of Humphry Davy’s work to France. These observations testify to Balzac’s “conscientiousness”: he prepared seriously for a subject that was foreign to him. He avoided the pitfalls of linking the work of modern chemistry to his unitary conception of Creation. Contemporary criticism of La Recherche de l’absolu does not concern its scientific accuracy: Balzac had few judges in this field among the literati of his time. Instead, he was criticized for idealizing the characters. A passage from Félix Davin’sIntroduction to Etudes de mœurs au XIXème siècle. Some critics have found something too ideal in the four individualities of this novel: the high qualities of genius are too lavishly lavished on Balthazar, and the devotion of his eldest daughter has seemed too magnificent, too continuous. Then, are there souls as loyal, as candid as Marguerite’s lover’s, hunchbacks as seductive, as imperial as Madame Claës?” Balzac’s spokesman responds weakly to these reproaches, basing himself on the writer’s “mission” “to elevate the beautiful to the ideal”. It’s a singular argument in Balzac’s defense. Raymond Abellio refers to this ending of La Recherche de l’absolu as a “fairy tale”. The truth must lie somewhere between this bold rapprochement and the cautious retreat into idealism.

The story This short story describes a family’s struggle and disarray in the face of the patriarch’s destructive passion and obsessive ideas. The scientist’s only motivation is the hope of discovering the Absolute, a hope that is always disappointed but always on the verge of success. This hope accompanied Balthazar Claes to the end of his strength, without bringing him the glory he had longed for. From an illustrious Flemish family in Douai, Balthazar Claës is a man fulfilled by life. Enjoying all the privileges of a fortune amassed over five or six generations, he leads the life of a grand bourgeois. Savant and erudite, Balthazar studied chemistry in Paris alongside the famous Professor Lavoisier. One could say that Balthazar was a man who had succeeded in life: adored husband, fulfilled father, everything smiled on him until that day in 1809 when Balthazar agreed to house Mr. Adam de Wierzchownia, a Polish officer. Driven by poverty to study chemistry, this soldier finds a friend in Balthazar. From then on, Adam confided to Claës the experiments he had carried out in an attempt to decompose simple bodies in order to discover the principle of matter, the origin of life. Requisitioned for a new military campaign, the officer left Douai, having passed on to Claës the demon of scientific research. With his mind completely taken up with his work, Balthazar now lives solely for and through the search for the absolute, the substance he believes to be unique and indistinguishable from all bodies in nature. This idea quickly became a fixed one, occupying all his thoughts – living reclusively in his laboratory, with his faithful valet Lemulquinier as his only helper, he no longer saw his family, forgot to live as a family, and forgot himself. He quickly squandered the family fortune. His incessant need for chemicals is totally ruining the family. Once the last penny has been squandered, he commits the furniture (the works of art, paintings and other riches accumulated over generations). He sold all his real estate, disinheriting his family. The unconditional love of his wife and children did nothing to prevent the family’s demise; on the contrary, through their submission and self-sacrifice, they unconsciously and instinctively contributed to the downfall of the House of Claës.

Pepita destroyed

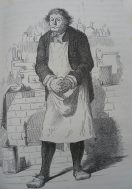

The faithful Lemulquinier

Work written and dated by the author in Paris, June-September 1834 Source analysis/history: Preface from the 24th volume of La Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs in 1987, based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris.

The characters Joséphine Claës: Born de Temninck, Pépita, wife of Balthazar. Balthazar Claës: Nobleman from Douai with a passion for chemistry, husband of Joséphine and father of four children, including two boys and two girls. Marguerite Claës: Eldest daughter of the Claës family, born in 1796. Félicie: 2nd daughter of the Claës family. Gabriel Claës: Son of Joséphine and Balthazar. Jean-Balthazar Claës: The last child of the Claës family. Lemulquinier: Valet whose loyalty to Monsieur Claës knows no bounds. Adam de Wierzchownia: Polish officer, chemistry enthusiast and friend of Claës. Abbé de Solis: Confessor, friend and confidant of Madame Claës. Claës-Molina de Nourho: Ghent family settled in Douai and represented by Balthazar Claës, born in 1761, died in 1832. Married Joséphine de Tenninck, born 1770, died 1816, from whom: 1) Marguerite married Emmanuel de Solis; 2) Félicie married Pierquin; 3) Gabriel married a Conynckx; 4) Jean-Balthazar. Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

Sources of inspiration Several sources of inspiration are cited for the character of Balthazar Claës. In Nice, we mention Arson Pierre-Joseph, a banker who wanted to buy the secret of the absolute from the Polish mathematician Hoëne Wronski. He spent over 100,000 francs over 16 years: 17 bills of 4,000 francs, 40,000 francs and an IOU of 108,516 francs. Perhaps 300,000 francs, according to an article in the Figaro of August 21, 1831, in the joking mode: “One day a man had 300,000 francs and didn’t have the absolute, M. Hoëne didn’t have 300,000 francs but he had the absolute”. Arson, furious at having been fooled, sued Wronski.

Source notes and additional information: Wikipedia.

No Comments