The Wild Ass’s Skin

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XIVth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1874)

Philosophical studies

THE WILD ASS’S SKIN (The Magic Skin) (1830-1831)

Analysis of the work With this novel, we enter a completely different part of Balzac’s work, and, if you like, another hemisphere of the Balzacian universe. Balzac rightly placed this novel at the head of the second part of his work, the Etudes philosophiques, which complement and to some extent explain the first part of the Comédie humaine, the Etudes de mœurs au XIXe siècle. There, no more descriptions, no more portraits of the century, no more sociological explorations: but demonstrations, as on the stage, of the strange and unknown powers of the imagination, magnifying phenomena that show the mechanism of passions, of moral suffering, and also the cause of prodigies, of second states, of divination, of all the oddities of which man, in certain circumstances, is the theater. Balzac is no longer the walker who guides his readers through the social map of the 19th century; he takes on another task, and presents himself in a different guise: he is the doctor who, with his scalpel, explains what he calls the “physiology” of human passions, presenting examples of how they function and their limits. As he had done for the Etudes de mœurs in the 19th century, Balzac asked Félix Davin for an Introduction to the ” Etudes philosophiques “, also written on his instructions. In his Introduction, he summed up his thoughts as follows: “For us, it is obvious that M. de Balzac considers thought to be the most vivid cause of the disorganization of man, and consequently of society. He believes that all ideas, and consequently all feelings, are more or less active dissolvers. Instincts, violently overexcited by the artificial combinations that create social ideas, can, according to him, produce sudden lightning strikes in man, or cause him to fall into a successive, death-like collapse. He believes that thought, augmented by the fleeting force lent to it by passion, and as society makes it, necessarily becomes for man a poison, a dagger. In other words, following the axiom of Jean-Jacques (Rousseau) the thinking man is a depraved animal…As man becomes more civilized, he commits suicide. The disorder and havoc wrought by intelligence in man considered as an individual and as a social being, such is the idea that M. de Balzac threw into his works.” Philosophical Studies, thus conceived, will be a series ofexamples. With the help of borderline cases chosen from exceptional situations, Balzac will demonstrate the fundamental mechanism found in so-called extraordinary situations, which produce results that astonish us because we don’t understand their laws. This is where Philosophical Studies and Moral Studies come together: Moral Studies show the effects, Philosophical Studies reveal the cause. This system of explanation, which Balzac claims is the key to the whole of La Comédie HumaineIt is also at the root of his vision of social drama, which for him is a shock and, at times, a cyclone caused by the violent collision of opposing collective passions. The dogmatic unity of La Comédie Humaine has long been overlooked. For a long time, Balzac’s best defenders were suspicious of the Etudes philosophiques, which they regarded as a kind of strange appendix to La Comédie Humaine, testifying to an esoteric curiosity that was certainly estimable, but cumbersome. The great German critic Ernst-Robert Curtius, in his essay on Balzac translated in 1933, was the first to present a complete and coherent explanation of La Comédie Humaine based on Balzac’senergetic approach, restoring the importance of the Etudes philosophiques. This interpretation has been generally accepted and confirmed by most specialists in Balzacian studies. It is essential to give Balzac’s work its full meaning, by making it clear that it is not just a descriptive fresco, but that it also proposes a certain definition of man and an analysis, still valid today, of the perils to which modern societies are exposed.

Ernst Robert Curtius

La Peau de chagrin does not set out the program of the Etudes philosophiques in its entirety: Balzac limits himself in this novel to presenting, in a striking way, the principle that will guide his investigations. He does this by means of a satirical and allegorical novel in which, however, all the situations and episodes are linked to the central idea that Balzac wants to develop. But Balzac’s novel is so sparkling and rich that it’s necessary to show how all these secondary branches, whose multitude and glitter can be misleading, are offshoots of a main trunk. First, a word about the date and circumstances of publication. La Peau de chagrin went on sale in August 1831. It was a year after the days of July 1830, which had overthrown the monarchy in favor of the “bourgeois royalty” embodied by Louis-Philippe, “King of the French”. As with all revolutions, this change was accompanied by a great effervescence of ideas and ambitions. New newspapers and magazines had appeared, and new reputations were being established. These newcomers aspired to distinguish themselves by leaving an indelible mark on the previous regime, and even by denouncing the contradictions of the bourgeois regime that had succeeded it. Charles Nodier, Jules Janin, Stendhal (who had just published Le Rouge et le Noir), and other lesser-known writers who competed with them, were all doing this. Balzac, who had just made a name for himself with Physiologie du mariage, was part of this group of iconoclasts. “They all have a paillasse, a caisse, a clarinet,” said Balzac of them, referring to their “fireworks”. And Sainte-Beuve did not characterize Balzac’s style any differently in La Peau de chagrin when he described his style as “fetid and putrid, witty, rotten, illuminated, papilloté and marvellous in the way it strings imperceptible pearls and makes them ring with a clatter of atoms”. La Peau de chagrin the path of a political itinerary. This sparkling jugglery at certain points in the book probably expresses nothing other than the desire to rise to the top, surpassing similar productions in the brilliance of its satirical display. This elegant skepticism was just a facade. Balzac took care to warn his readers of this, having Philarète Chasles, then his friend, say in a preface written for the2nd edition: “Some critics have failed to see that La Peau de chagrin is the expression of human life. “Indeed, that was the point of the book.

Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve

The whole meaning of the novel is summed up in the explanations the antiquarian gives Raphaël when he abandons the talisman. The incidents in the novel are simply an application of this. “I’m going to reveal to you in a few words,” he told her, “a great mystery of human life. Man is exhausted by two instinctive acts that dry up the sources of his existence. Two verbs express all the forms taken by these two causes of death: to want and to be ableto…To want burns us and to be able to destroys us. ” And as he presents the peau de chagrin, he explains: “This is the power and the will. reunited. Here are your social ideas, your excessive desires, your intemperances, your joys that kill, your pains that make you live too much… Your wishes will be scrupulously satisfied, but at the expense of your life. The circle of your days, represented by this skin, will tighten according to the strength and number of your wishes, from the lightest to the most exorbitant.” Raphaël’s first wish is granted. But in this feast where the guests judge all philosophies, that is, all vain formulations of the pursuit of happiness, Raphaël, almost drunk, finds the old man’s warnings in the disillusioned confession of two courtesans. They tell him about their lives, and conclude by asserting the contradiction between vital egoism and sensitivity: “To kill feelings in order to live old, or to die young by accepting the martyrdom of passions, that is our stop.” At this point, when the choice is made between immobility (and non-desire) on the one hand, and concupiscence (and the price to be paid for it) on the other, the reader, looking back on the other incidents in the novel, understands the symbolic significance of each of them. For Raphaël, gambling and suicide, before the discovery of the talisman, are a way of posing the terms of the problem of the life of enjoyment, similar to the one that will be proposed to him by the peau de chagrin: gambling brings wealth, it’s a quick way of satisfying one’s desires, but in the event of defeat, it leads to suicide, which is the price one pays for enjoyment. The wealth of vanished civilizations piled up at the antique dealer’s answers the total skepticism of the banquet guests: empires leave only ashes, the future contains only mirages. Finally, in the story of Raphael’s impoverished youth, the pure, peaceful love and calm of a life without ambition are represented by Pauline, poor like him, gentle, unselfish, who loves him in silence, while the glitter of worldly life, the selfishness of the rich, their fatigue and the vanity of their triumphs are represented by Countess Foedora, the “heartless woman” who symbolizes the vanity of worldly success and the indifference of the powerful. In this way, everything responds and organizes itself, and the succession of incidents only serves to demonstrate man’s powerlessness in the face of life’s problems. So Raphaël realizes that science and medicine are equally powerless when it comes to things that are not their specialty. Their failure is the same as that of the philosophies and political systems condemned in a single word by the guests at the banquet. So Raphaël turns to the humble. He finds in them greed and selfishness hidden beneath an apparent bonhomie that quickly reveals a kind of animal ferocity. All over the world, he found greed and selfishness, the two forms that men have given to the fatal union of will and power. Like him, they have a skin of sorrow that shrinks with each of their actions.

François-Bernard Balzac

Wisdom consists in abstaining and, as the old man in the first pages had recommended, in looking at life and the passions of men as a spectacle in which one refuses to participate. Balzac inherited this theory, which contrasts the reckless loss of vital energy with its rational use and economy, from his father, the elderly François-Bernard Balzac, who had just died in 1829 after a long and prosperous life cut short by an accident. Cautious, methodical, vegetarian, claiming to feed on tree sap, old François-Bernard had built up a system of longevity through which he hoped to make a fortune. He was a subscriber to a mutual insurance company known as the Lafarge tontine, a fund financed by its members, which was to revert entirely to the last survivor. He had the ambition to be one through this wise economy of his forces. It wasn’t. But he bequeathed to his son Honoré this original theory, which Balzac turned into a system of passions. Indeed, he drew the conclusion that the exclusive concentration of the vital force on a single preoccupation explains the terrible passions of the “monomaniacs” he describes in La Comédie Humaine. It’s this focus of all their forces on a single objective that gives them their power, but is also for them an inescapable cause of decay and death. In this way, the thesis of La Peau de chagrin can be found everywhere, in unexpected forms, in La Comédie Humaine.

Raphaël

All the passionate, all the ambitious, all those who live a violent life driven by desire have their skin in the game: it doesn’t grant all their wishes, but it shrinks as implacably as the one that represented for Raphaël the destiny that was placed in his hands.

The story So here’s the story. Raphaël de Valentin, who has just lost his last gold coin in a game of chance, decides to commit suicide by throwing himself into the Seine. As he waits for nightfall, he enters an antique store, where treasures from all eras have been accumulated. The merchant is a very old man, almost a hundred years old, who offers Raphaël a sorrow skin, a piece of evening primrose skin, an ancient magical object which, he tells Raphaël, represents the life of its owner and has the power to grant all his wishes, but shrinks each time, thus shortening the life it represents. Raphaël smiles and accepts. He asks the talisman for a sumptuous banquet and wealth. Immediately he is bumped into at the store’s threshold by a friend who invites him to a grand dinner given by a financier to journalists and writers. The dinner was brilliant, with a review of all the prospects opened up by the 1830 revolution and all the disappointments it had caused.

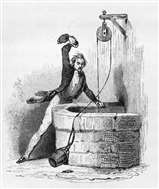

La Peau de chagrin merchant

has already caused. Over dinner, Raphaël recounts his life as a student without a fortune, and ends by sighing after wealth.

Raphaël throws away the skin of sorrow

In the morning, amidst the sleeping guests, a notary appears and tells Raphaël of a fabulous inheritance. Raphaël looks at the skin and sees that it has shrunk considerably. He understands that, from now on, his life expectancy will decrease with each of his desires. Then the second part of the novel begins. Raphaël, worried, consults: science is powerless. He’s irritated, throws off the skin out of spite, decides to enjoy his fortune and satisfy his every whim. A few months later, the skin of sorrow has shrunk to the size of a small tree leaf. Terrified, Raphaël devoted himself to a vegetative life, taking refuge in the desert of Auvergne. There he discovered all the forms of human selfishness, and, discouraged, returned to Paris. He finds the girl who loved him when he was poor, and who still loves him. He pushes her away out of fear of desire. This renunciation is pointless, since he was offered this love without having to ask for it. But it’s too late. He dies beside her, and she goes mad.

The main characters Raphaël de Valentin Raphaël de Valentin, son of the Marquis de Valentin and Barbe O’Flaherty, Irish, desargenté noble family from Auvergne – Born 1804 – Died 1831.

Foedora

Foedora Countess Foedora, a heartless, selfish, egocentric woman whose existence is occupied by nothing but pleasure and enjoyment. His motto: Don’t love, don’t feel, don’t suffer. Pauline

Pauline

Daughter of Raphaël’s landlady, when he was poor. He gave Pauline piano lessons to supplement his income. Pauline is secretly in love with Raphaël, who pretends to ignore this attraction to pursue a nobler passion. Jaded and disillusioned with life, he finally finds true love and happiness, too late, with Pauline. Henri de Marsay A dandy and Raphaël’s friend, he is the first person Raphaël meets after his visit to the antique dealer, and the one who invites him to the banquet that evening. We see him regularly throughout the novel. Marsay line: Old man who married Miss X, already pregnant with Lord Dudley’s child, and who, as a widow, married the Marquis de Vordac. The result was a son, Henri (actually Lord Dudley’s son), born in 1792 or 1801. Around 1827, Henri de Marsay married Dinah Stevens, born in 1791. Old Marsay had a sister who remained an old maid. (Félicien Marceau – Balzac et son monde – Gallimard) Aquilina and Euphrasia Aquilina and Euphrasia are courtesans who frequent Countess Foedora’s salon. Euphrasie is a dancer. … ” A poet would have admired the beautiful Aquilina the whole world had to flee the touching Euphrasia “, who in fact turned out to be detestable.

Euphrasia and Aquilina

At the Georgia party organized by Jean-Frédéric Taillefer, Aquilina confides in Raphaël de Valentin the origin of the red fabric she hangs on all her clothes. The sign is a tribute to Léon, her lover who was guillotined in the Place de Grève. Aquilina is a courtesan who features prominently in the parties and orgies of Balzac’s novels and short stories. 1)

Source: Preface and story compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (tome XXII) published by France Loisirs 1987 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac. 2) Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau – Balzac et son monde – Gallimard

No Comments