Gambara

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XVIth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Philosophical studies

GAMBARA

Dedicated work, TO MR. MARQUIS DE BELLOY It was by the fireside, in a mysterious, splendid retreat that no longer exists, but will live on in our memory, and from which our eyes discovered Paris, from the hills of Bellevue to those of Belleville, from Montmartre to the Arc-de-Triomphe de l’Etoile, that, on a morning drenched in tea, through the thousand ideas that are born and extinguished like rockets in your sparkling conversation, you, prodigal of spirit, threw under my pen this character worthy of Hoffman, this bearer of unknown treasures, this pilgrim seated at the gate of Paradise, having ears to listen to the songs of the angels, and having no tongue to repeat them, waving on the ivory keys fingers broken by the contractions of divine inspiration, and believing to express the music of heaven to stunned listeners. You created GAMBARA, I just dressed it up. Let me render to Caesar what is Caesar’s, while regretting that you do not grasp the pen at a time when gentlemen must use it as well as their sword, in order to save their country. You may not think about yourself, but you owe us your talents.

Analysis of the work Gambara is a tale that appeared in May 1837 in La Gazette musicale, a magazine edited by Maurice Schlesinger, and provided Flaubert with the model for Mme Arnoux’s husband in L’Education sentimentale. It’s the transposition, in the musical realm, of the phenomenon of illusion that Balzac had shown in old Frenhofer in The Unknown Masterpiece. René Guise describes the parallels between the two works as follows: “In both cases, we’re dealing with a genial, whimsical artist, capable of critical commentary, learned and judicious in his approach to the work of others, also capable of remarkable execution, but who, when it comes to the work of which he dreams and which he carries within him for too long, ends up nothing but a failure”. Naturally, Hoffmann is at the origin: in this case, it’s a question of Salvator Rosa features a manic old man, who gets drunk like Gambara, but who then, instead of regaining his sanity in drunkenness, draws from it the illusion that makes him mistake his cacophonies for magnificent operas. And, of course, Gambara ‘s theories on music correspond to Master Frenhofer’s theories on painting, and his analyses of operas are the equivalent of Frenhofer’s criticisms of Porbus’s paintings. This parallelism, however, is only part of the Gambara story. This tale, to which Balzac gave his name, was the subject of some strange tribulations. The treaty with Maurice Schlesinger was signed on October 13, 1836. At the time, Balzac was overwhelmed by the lawsuits he was facing as a result of the collapse of La Chronique de Paris. He had been forced to flee his home to avoid debtors’ prison, and had taken refuge in a rented apartment in Chaillot. The thousand francs paid by Schlesinger were very welcome in this debacle. As Balzac had a number of commitments, he had to move quickly to provide the tale required for the end of the year or, at the latest, for January, the re-subscription period. It is probable, as Maurice Regard thought, that Balzac entrusted his secretary, the later Count and Marquis Auguste de Belloy, who had provided him with the subject of the story, with the task of writing the first pages. Much of the manuscript submitted at the end of January was being typeset at Everat, 16, rue du Cadran, when the printing works burned down on Mardi Gras night, February 7, 1837. Proofs had been made of the first 10 leaves, which escaped the fire, but the manuscript of the entire central part was destroyed. “We have the head and the tail without the middle,” Balzac observed sadly. This accident was all the more serious as Balzac had to leave for Italy to arrange a trial for his friends Guidoboni-Visconti. He left it to Belloy to reconstruct the central part and complete the story. When Balzac returned from Italy on May 3, 1837, he was rather disappointed by the version of Gambara presented to him. He was even so discouraged that he suggested to Schlesinger that he give him another short story on a musical subject. Massimilla Doni. The substitution did not take place, and Balzac contented himself with completing and reworking the proofs of Gambara by means of long and numerous additions, which required nine successive sets of tests. These facts probably explain the warm dedication Balzac wrote at the head of Gambara for the Marquis de Belloy, who did more than just bring him the idea he was thanking him for. Through its similarity to The Unknown Masterpiece, Gambara can be seen as another application of the destructive effects of contemplation. But it’s also an exposé of Balzac’s ideas on music, and in particular on the relationship between harmony and melody. These ideas are expressed in lengthy analyses of Gambara’s imaginary opera Mahomet and Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable. Musicians at the time were divided between supporters of Rossini and Meyerbeer. Schlesinger’s magazine supported Meyerbeer, and the short story commissioned from Balzac had to agree with the opinion expressed in its columns, although Balzac himself preferred Rossini’s music. These presentations may seem a little long to the reader today. Beethoven, quoted several times in Gambara, appeared as an avant-garde musician, a kind of enlightened man. It’s not impossible that Balzac thought of him when he imagined his Gambara. Jules Janin, then considered the best music critic of his time, had written a short story three years earlier, Beethoven’s Dinnerin which one of the great musician’s listeners moaned about his “shrill sounds” and his “discordant symphony”, and at the same time showed Beethoven “lost in the sweetest ecstasies”, improvising under the influence of intoxication.

Preface from the 23rd volume of La Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs in 1987, based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris.

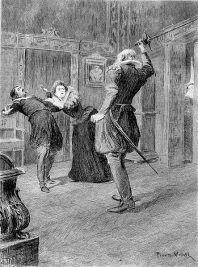

The story Count Andrea Marcosini, a nobleman from Milan, is strolling through the Palais-Royal when he discovers in the crowd the extraordinary face of a woman with fiery eyes. She flees from him, but he pursues her into the sordid alleyway behind the Palais-Royal, where she disappears. If he “attached himself to the steps of a woman whose costume announced a deep, radical, ancient, inveterate misery, who was no more beautiful than so many others he saw every evening at the Opera”, it was because her gaze literally bewitched him. Immediately, the Count investigates and discovers that the woman is married to a music composer: Gambara, also an instrument maker, with disconcerting theories and practices on music. His music is only beautiful when he’s drunk. Mariana sacrifices herself for him, doing the most humiliating jobs to keep the household going, because she firmly believes in her husband’s misunderstood genius. In order to better seduce Mariana, he proclaims himself the couple’s friend, and initially provides materially for the couple’s needs. Manipulative to the core, the Count finally kidnaps the beautiful Mariana, abandoning her for a dancer. Mariana returns to her husband in total destitution, finding him in the deepest poverty. Paris, June 1837

Part of the story and some of the arguments are taken from Wikipedia, the universal encyclopedia.

Charles Louis Gratia

La liseuse: Portrait of Charles Louis Gratia. Everything suggests that the artist was inspired by the Countess Guidoboni-Visconti to paint his reading light.

The characters Marcosini: Andréa, Milanese in Paris. Gambara: Paolo, Italian musician, born in 1791; married a Venetian woman, Mariana.

Source characters: Félicien Marceau: Balzac et son monde -Gallimard.

No Comments