Pathology of Social Life

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Pathologie de la vie sociale is not included in the complete works of H. DE BALZAC, published in 1877 by Veuve André HOUSSIAUX, publisher, Hébert & Cie, Successors, 7, rue Perronet, 7 – Paris.

Volume XXVIIIth – Analytical studies

SOCIAL PATHOLOGY

Analysis Well defined in the Preamble that Balzac placed at the head of his Traité des excitants modernes when it was first published in 1838. Also by its subtitle: Méditations mathématiques, physiques, chimiques et transcendantes sur les manifestations de la pensée sous toutes les formes que lui donne l’état social soit par le vivre et le couvert, etc. In the explanations Balzac provides, he presents his project as follows: after marriage and settling into life, man finds himself chained by social life, “obeying all the fantasies that society has developed in him, all the laws it has brought about”. The aim is to “observe the disorders” caused by this pressure system. Balzac adds: “The state of society makes our needs, our necessities, our tastes, so many sores, so many diseases, by the excesses to which we lead ourselves, driven by the development that thought imparts to them… Where there is no physical disease, there is moral disease.” And Balzac concludes with the key word that best expresses what he wants to do: “A complete anthropology that is lacking in the learned, elegant, literary and domestic world.” New territory is opened up in the exploration of the “ravages of thought”. It’s not only civilization, but above all society, the concrete expression of civilization, that turns man into a “depraved animal”. This is the physiological conclusion that Balzac wanted to add to his Etudes de mœurs au XIXe siècle . Balzac did not have the time to complete this ambitious project, which was still only the first building block of the dome with which he wanted to crown La Comédie humaine, the Etudes analytiques.

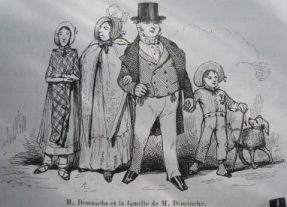

Monsieur Dimanche and Monsieur Dimanche’s family.

These Analytical studies were to include, in addition to the The physiology of marriage and Social pathologya Anatomy of the teaching profession which was to be, as Balzac explained it, a theory of eugenics and human ecology, and a Virtue monograph which, according to Preamble already quoted, a description of the adventitious varieties of virtue defined for each generation or century by the social state, and which was to show the differences that exist at all times between natural virtue and that virtue defined by the vagaries of history. And all this was to be “summed up” by an Essai sur les forces humaines and a Histoire de l’Eglise primitve, which Balzac did not define, but whose content can be surmised from the ideas expressed in Louis Lambert. Pathology of Social Life is just one part of a larger project. It was to consist of three studies, partly drafted, the Traité de la vie élégante, the Théorie de la démarche and the Traité des excitants modernes. What these three fragments have in common is that they describe the deformations, distortions and physiological corruptions that civilization imposes on the human animal, transforming and atrophying it. Of these three fragments, two are clearly incomplete and the third is a summary study. We can therefore only imperfectly judge Pathologie de la vie sociale from these sketches, which Balzac would probably have expanded for publication in the edition of La Comédie humaine.

From left to right: 1) Eighth-grader, very strong, out as a favor; 2) Home cook – fortnightly outing; 3) A seminarian visiting his aunt.

A Parisienne is a lovely mistress, an almost impossible wife, a perfect friend.

The first of these three fragments is Traité de la vie élégante, published in La Mode in late October and early November 1830. In this first publication, it did not bear Balzac’s signature. A passage from this Treatyconfirmed by the magazine’s announcements and notes, indicates that it was the result of discussions in which Emile de Girardin, the publication’s director, and a number of Compagnons du boulevard de Gand, the brilliant Lautour-Mézeray, Eugène Sue and perhaps Hippolyte Auger, all regulars on Tortoni’s stoop, where elegant people leered at passers-by, took part. Balzac was rightly given the task of writing the sentences of this Sanhedrin: a few years earlier, during his industrious youth, he had been one of the anonymous team members brought together by Horace Raisson to write the Code gourmand, Code de la toilette, Art de mettre sa cravate to which Raisson put his name and which had preceded the literature of impertinence whose A treatise on elegant living can be regarded as a specimen.

Traité de la vie élégante has a didactic tone. It begins with a serious preamble in which, as at the beginning of the Physiology of Marriage, we classify the small portion of humanity that is capable of benefiting from the master’s advice. The subjects who can lay claim to the “elegant life” are as few as the women who fit the definition of the “proper woman”. These are the people whose social status allows them to approach the beaches of elegance, and who also possess an innate sense of that elegance. A consultation by the famous Brummel, then pitifully sheltered in Boulogne, sets out the field to be explored by the doctors of this science and indicates the obligatory divisions of the Treaty a meditation on the metamorphosis that grooming imposes on the human creature, a second part laying down the “laws” of the elegant life, a third part devoted to “things that proceed from the body”, and a fourth part devoted to “the body”. immediately of the individual”, i.e. first the grooming, then the voice, manners and attitude that must accompany it, and finally a fourth part “intended for the things that proceed mediately of the individual” and are therefore accessorieslike the car, the people, the table, the furniture, etc. The language used in this grave enumeration gives an idea of the tone that will be maintained throughout the essay.

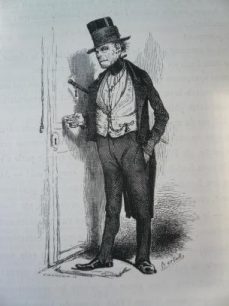

People in Paris, and people from all over the world.

Of the four parts defined with Brummel’s help, only the first two appear in the Treatise, one of them the preamble described above, the second devoted to the dogmas of elegance, which teach us that the obligatory principles of all elegance are sobriety, harmony and ease. Unfortunately, that was the end of the story. A third part is begun, announcing five chapters, of which only the first has been written. The Treaty was interrupted at this point, as La Mode disappeared shortly afterwards following the dispersal of its clientele, who had fled to its châteaux in the wake of the July Revolution. The project was not taken up again. Reading this Traité de la vie élégante, the reader is tempted to wonder about the Etudes analytiques of which it was to be a part. The lightness of tone, the brilliant, boulevardière form, the journalistic veneer that were an element of success in 1830, are today no more than dated ornaments: their borrowed brilliance is precisely the opposite of that simplicity which Balzac recommends for elegance and which is no less recommendable when writing. Balzac’s advice isn’t very original. He teaches readers with a certain natural taste, or simply common sense, nothing by telling them that “anything aimed at effect is in bad taste” and even by asserting that “dandyism is a heresy of the elegant life”.

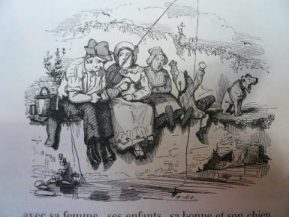

With his wife, children, maid and dog

These rulings were to be found twenty years later in the Baroness de Staff’s books, which are useful for housewives but make no claim to depth.

It’s through a certain historical reflection on the evolution of mores that Traité de la vie élégante can hold our attention. We often discover the Balzac we know, and sometimes an unexpected Balzac. The starting point for this reflection on elegance is interesting. It’s a point of view on the social mechanism: “How is it that the one who sows, plants, waters and harvests is precisely the one who eats the least?” Balzac promises an answer to this question about the inequality of conditions: “We shall perhaps give the explanation later, when we come to the end of the life followed by mankind.” But this explanation was never given. Yet one word, a little further on, indicates as much: “For as long as societies have existed, a government has necessarily been an insurance contract concluded between the rich against the poor.” This vigorous thought has no future, despite the prologue to theHistory of the Thirteen in a different form.

At six o’clock, the lions get papillotes, and to prepare for their evening success, they deliver their heads to the barber and their feet to the pedicurist.

But this theory on the distinction between luxury horses and Percherons is the secret, invisible thought that inspires the Traité de la vie élégante, just as it inspired the Physiologie du mariage. Elegance,” explains Balzac, “was born of the Revolution. Before this date, men were separated by caste, and this distinction was so fundamental that no proof was needed. This classification between men having been “abolished”, it had to be replaced: “And in the year of grace 1804,” Balzac explains, “it was recognized that it was infinitely pleasant for a man or a woman to say to himself or herself, looking at his or her fellow citizens: I am above them, I splash them, I protect them, I govern them, and everyone sees clearly that I govern, protect and splash them, for a man who splashes, protects or governs others, speaks, eats, drinks, sleeps, coughs, dresses, amuses himself, differently from the people splashed, protected or governed. “These nuances, which we recognize in luxury horses, are what elegance is all about. They have replaced visible or recognized differences. Everyone is therefore obliged to make their social superiority felt by demonstrating the superiority of their taste. And we come back to Etudes de mœurs : “Don’t we imprint our morals, our thinking on everything that surrounds us and belongs to us?” The reader joins La Maison du chat-qui-pelote.

Women also have their cold baths, which cost 20 centimes… the bathers, dressed in dark black or brown wool, are naked only in the neck, feet and arms.

Loyal and vulture “On April thirty next, it will please you to pay, to his order, the sum of one thousand ecus…”.

This itinerary leads us to reflect on the dual character of both Traité de la vie élégante and Etudes analytiques. In a way, this essay and those that follow are nothing more than the reunion in a single text of the digressions that Balzac inserted into his novels, which are like the sociologist’s continuous commentary on the milieu he describes and the action he recounts. But at the same time, the Traité de la vie élégante and, a fortiori, the Etudes analytiques must be something else. There must be an explanation of the social mechanism and a judgment. At the end of these reflections, there is a serious question that will be found in the three “Treaties” that make up the Social pathology Are we, ourselves, or what society makes of us, what our social rank, our occupations, our social conformism, we would say today our disposalWhat do they make of us? We find Jean-Jacques Rousseau at the origin of this thinking and, in the end, we follow a line parallel to that of Karl Marx. What would have been the conclusion of the Analytical Studies ? The Théorie de la démarche, which appeared in 1833 in the magazine L’Europe littéraire, is a sequel to the Traité de la vie élégante : it is a kind of complementary monograph devoted to a characteristic detail. But in reality, it’s just as incomplete as the Traité de la vie élégante, because Balzac ends it on a contradiction he can’t resolve. The Théorie de la démarche consists of two parts, one in which Balzac describes how the theory he expounds came to his mind, the other a series of observations and conclusions. In the end, Balzac discovers the contradiction he hasn’t answered.

– What? My late cousin left only this? I ask you, Madame Lézardé, in the 37 years since he was a pharmacist… Madame Lézardé, my late cousin must have had funds invested… – In the Caisse apothicaire…

The first part is very curious, because it seems to answer a question that a number of Balzacians have asked themselves and to which they have been unable to give a complete answer: how did Balzac elaborate theenergetics on which his entire physiology is based? Does it come from readings, influences or personal intuition? Balzac’s reply is dodged and replaced by a joke. But it’s interesting that this captious explanation was given by Balzac at a time when his energetic system, based in part on direct experience, had just been expounded in Louis Lambert, the first edition of which appeared in 1832, and after it had been repeated the same year in his Letter to Charles Nodier on human palingenesis. From the very first page of his Theory of GaitBalzac defines the question he sets out to answer: “How much fluid could man, by a more or less rapid march, lose or save in strength, in life, in action, in the je ne sais quoi we spend in hatred, in love, in conversations and in digressions? After three pages of irritating boulevardier chatter, he then cites the two experiences of his youth (the anecdote is set in the year 1822, when he was passionately reading Lavater’s twelve in-8° books, which he had paid for with all his savings) that gave rise to his reflections. In the courtyard of the Messageries, he saw a man indulging in overabundant gesticulation because he’d lost his balance getting off the stagecoach, and, in another circumstance, he saw his sister expending useless energy lifting a cassette she thought was heavy and wasn’t. These two superfluous movements, these expenditures of energy “in pure waste”, evoke memories and observations in him, and he concludes that man unknowingly lavishes “a more or less abundant outpouring of life” that others, artists, men of action, laborers, spend in acts or works, and he concludes: “I decided that man could project outside himself, through all the acts due to his movement, a quantity of force that must produce some effect in his sphere of activity.”

A mother

Armed with this research principle, he then chose examples that would show him “what energy we expend in our movements”, or “what are the laws by which we send more or less force from the center to the extremities”, or “what phenomena this faculty should produce in the atmosphere of each creature”. In vain, he read Borelli, a movement theorist, who did not resolve these difficulties. But on the one hand, he points out that any movement we make is echoed ad infinitum by the waves it provokes, and that, on the other, any excessive prodigality of energy can result in a sudden death similar to a haemorrhage, which he defines by a comparison: as if “the pitcher had emptied itself”. These anecdotes are interesting because of their date. But this is just one stage in the still obscure history of intuition, which Louis Lambert ‘s biography traces back to the Collège de Vendôme. This relay reported in 1822 joins other indications given in the Physiology of Marriage : it’s just another milestone. Afterwards, Balzac decided to continue his investigation, and the next day sat on a chair on the boulevard de Gand (that’s our boulevard des Italiens) to watch the strollers. This is where the Theory of Gait comes in, devoted to observing and classifying what each person’s gait teaches us about themselves. This bit of observation is fun and deeper than it looks. Each person’s approach, and even more so their attitude, is a mask, an outward appearance that disguises them, but at the same time betrays them.

The man you’ve got there, my little mother, I’m telling you: he’s not much. – Mosieu is a peer of France?

For the observer, it’s a question of “capturing the most hidden movements”, the little that each person “involuntarily allows to be guessed from his consciousness”. After commenting on a few examples, Balzac decides: all our gestures “are imbued with our will and are of frightening significance. It’s more than speech, it’s thought in action. Hence the corollary: “A simple gesture, an involuntary quiver of the lips can become the terrible denouement of a long-hidden drama.” And the theory ofexpression is then formulated as follows: “Thought is like steam. Whatever you do and however subtle it may be, it needs its place, it wants it, it takes it.”

“I saw her enchanting smile, I kissed her half-open mouth, and I thought I was kissing a flower!”

Balzac’s purposely “cavalier” presentation only allows us to glimpse the perspectives he is merely sketching. Yet these points of reference are all the reader needs to discover some of the keys to Balzac’s work. First of all, gestures, the “fluid projection of thought” attitude and all the other “physical demonstrations of thought” are so many depositions about each man, they are the particular signs of his psychological passport. This is the key to the Balzacian novel’s method of observation, or rather detection: everything is a sign – attitude, expression, accessories, clothes, furniture, home – so many grids to decipher. Thought and sensitivity can be read everywhere, on everything. They are involuntary testimony. Secondly, the way in which each man uses and spends this vital energy that has been given to him, indicates his social ranking: and because, in most cases, man is not free to choose the application he will make of his vital energy, it denounces the constraint that the social order places on all men and the injustice of their condition. In the Theory of the Process that we come across Balzac’s so accusatory, so Marxist: “It was proved to me that the man busy sawing marble was not a beast by birth, but a beast because he sawed marble.” And he explains, “He passes his life in the movement of his arms as the poet passes his in the movement of his brain.” The entire social hierarchy, as described in Prologue to Histoire des Treize is in this sentence: the different zones of the social hierarchy correspond to the modes of vital wear imposed on each social function. Balzac’s human zoology is based entirely on this observation. Finally, since thought and action are only ways of using vital energy, they are the source of biological wear and tear in every individual. This is the aphorism that concludes the section of the Theory of Gait devoted to observation: “Every exorbitant movement is a sublime prodigality.” This aphorism serves as a transition. Balzac found an illustrious example of this economy of vital energy in Fontenelle, the famous valetudinaire who lived for a hundred years and lived through his century with “neither virtue nor vice”, neither emotion nor anger, cultivating calm and immobility in all circumstances. This example is a source of perplexity for Balzac. “What wears us down most are our convictions,” he writes. And he thinks of our useless passions, our vain restlessness, our perpetual anxiety. He contrasts the jerky movements, efforts and affectations of human beings with the natural, graceful movements of animals. “Civilization corrupts everything”, he exclaims at this point, and repeats the word that served as the starting point for all his meditations, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s famous phrase in his Discourse on Inequality The man who thinks is a depraved animal”, from which he drew the application he made to his own time: “Thought is the power that corrupts our movement, that twists our body, that makes it burst under its despotic efforts, it is the great dissolver of the human species.

Little Father Fromenteau

In the carnival

So does Fontanelle’s example give us the ideal image of the wise man? Should we imitate Asian immobility? But then, is the ideal man the concierge who sleeps by his stove, or the rentier who gets a kick out of watching the bowlers? Isn’t human history the history of human energy? Thought wears them down, but it’s thought that makes them masters of things. Should we accept to die young after a full life, or delay an inevitable death by accepting a life of atony and immobility? Should we wish Fontenelle longevity or the fate of Napoleon? It’s a question already asked by a courtesan to the half-drunken guests at the banquet in La Peau de chagin. Balzac doesn’t conclude. He stands by this contradiction, which his own life was to illustrate so cruelly. Traité des excitants modernes is an application of the ideas expressed in Théorie de la démarche. Written in 1839 and published following a reprint of the Physiology of taste by Brillat-Savarin, the A treatise on modern excitants is devoted to alcohol, sugar, tea, coffee and tobacco, described as substances that are pleasant to use, but whose excessive use is dangerous for the body. Opium is not mentioned, although Alfred de Musset published The Opium-Eating Englishman in 1828, based on the confessions of Thomas de Quincey, and Balzac himself described its effects in an 1832 article entitled Voyage de Paris à Java. It is above all against the excessive use of these stimulants that Balzac warns: these excesses, he says, contribute to the debilitation of the human race. But Balzac extends his reflections, and in this way this little treatise is part of the Pathology of Social Life. It’s not just these excesses that threaten people and nations. His reflections lead to a more general rule: “The destinies of a people,” he writes, “depend on both their food and their diet. This ecological maxim does not reveal an unexpected Balzac: it fits in perfectly with his distrust of the disorders that all civilization brings about by distancing mankind from the natural laws that apply to all biological species. It’s difficult to judge the Pathologie de la vie sociale project from these fragments. Balzac’s three opuscules are no more than guideposts. They mark out an itinerary that we can presume, but which is adventurous to describe. We can only regret that Balzac didn’t have the time to develop this confrontation between natural laws and civilization, which is based on analyses as useful for our time as for the one Balzac was describing.

Source analysis: Preface, study compiled from the full text of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1986 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

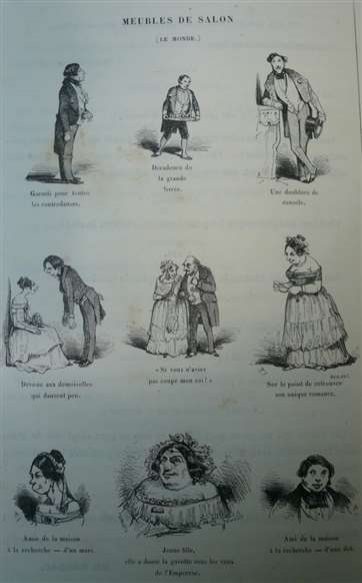

Living room furniture ( Le monde)  From left to right: Image 1) Guaranteed for all contredanses, Image 2) Decadence of the large livery, Image 3) A console liner, Image 4) Devoted to ladies who don’t dance, Image 5) “If you hadn’t cut the king!”, Image 6) On the verge of rediscovering his only romance, Image 7) Friend of the house looking – for a husband, Image 8) As a young girl, she danced before the emperor’s eyes, Image 9) Friend of the house looking – for a dowry.

From left to right: Image 1) Guaranteed for all contredanses, Image 2) Decadence of the large livery, Image 3) A console liner, Image 4) Devoted to ladies who don’t dance, Image 5) “If you hadn’t cut the king!”, Image 6) On the verge of rediscovering his only romance, Image 7) Friend of the house looking – for a husband, Image 8) As a young girl, she danced before the emperor’s eyes, Image 9) Friend of the house looking – for a dowry.

Source: engravings and captions by Gavarni, Le Diable à Paris (1845)

No Comments