Little Miseries of Conjugal Life

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XIIIth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

THE MISERIES OF MARRIED LIFE

THE MISERIES OF MARRIED LIFE

(Petites Misères de la Vie Conjugale)

Analysis In the present volume, we print Petites misères de la vie conjugale, followed by fragments of Pathologie de la vie sociale : le Traité de la vie élégante, la Théorie de la démarche and le Traité des excitants Modernes. These additions to the Etudes analytiques, the third of the great divisions of the Comédie humaine, had not been included in the 1842 edition prepared and presented by Balzac. In this edition, the Analytical Studies are represented only by the Physiology of Marriage. Nor were these additions listed in Amédée Achard’s 1845 catalog of works to be included in “La Comédie humaine “. Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale was only added to La Comédie humaine in 1855, after Balzac’s death, in a tome of posthumous works by a new publisher, Mme Houssiaux, who had bought the rights from Furne and Hetzel, the licensees of the 1842 edition. As for the three fragments presented under the title Pathologie de la vie sociale, they were later added to the editions of La Comédie humaine and incorporated into the Etudes analytiques, to which they obviously belong.

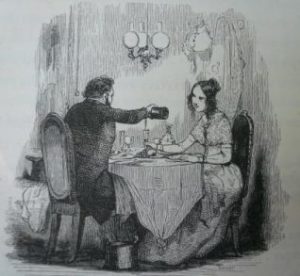

Petites misères de la vie conjugale (Written by Honoré de Balzac in Paris, 1824-1829) This essay, published in 1846 by both Chlendowski and the publishers Roux and Cassanet, is regarded by Balzac as a sequel to Physiologie du mariage. He had already announced it to Madame Hanska in December 1843 as a work that was “to be included in a new edition of the Physiology of Marriage “. Similar terms were used in the contract he signed with Chlendowski in February 1845, specifying that the work “was to be inserted in the Physiology of Marriage “. The publishers Roux and Cassanet even presented Balzac’s new work under the title Physiologie du mariage, Petites misères de la vie conjugale. Despite these statements, it is clear that Balzac had neverintended a sequel to Physiologie du mariage. In reality, Petites misères de la vie conjugale is a work on the bangs of La Comédie humaine, and does nothing to fill in the blanks in Balzac’s overall plan. It was a simple financial operation, for which Balzac used “fonds de tiroir” or “croquis de mœurs” that he had published some time before in various publications.  Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale is made up of thirty-five humorous scenes from different periods of Balzac’s output. He presented them by attributing them to two symbolic characters, a husband he called Adolphe, and a young wife he called Caroline. Two of the scenes from this young couple’s married life, one describing a doctor’s visit requested by Madame, who is suffering from vapors, the other recounting Caroline’s misunderstanding of a friendly couple of lovers she saw caressing in the building across the street, are two short articles Balzac had published in La Caricature, a satirical newspaper to which he contributed in 1830. Eleven other scenes had appeared in 1839, under the general title Petites misères de la vie conjugale, in another series of La Caricature called La Caricature non politique. Most of them are placed in the first part of Petites Misères. A third series of ten scenes was finally published in Hetzel’s collective collection Le Diable à Paris in August 1844, under the title Philosophie de la vie conjugale. Most of these scenes also belong to the first part of Petites misères de la vie conjugale. Hetzel was so pleased with the public’s response that he published his articles in an in-12 booklet in 20 issues at 15 centimes, on sale from July to November 1845 under the title Paris marié. It was apparently the success of this operation that gave Balzac the idea of taking it up again in a more extensive form. As early as December 1845, he had a final series of “scenes” published in the daily La Presse, most of which now make up the second part of Petites Misères, thus providing him with the material for a volume. At the same time, Balzac was signing a treatise on the Petites misères de la vie conjugale with one of his new publishers, the Pole Chlendowski, a treatise that did not put an end to his book’s adventures. Indeed, 1845 had been a year of travel and vacations for Balzac. It was one of the happiest years of his life. He devoted part of it to a joyous trek across Europe in the company of Madame Hanska, her daughter Anna and her fiancé, Count Georges Mniszeck. On April 25, 1845, Balzac joined Madame Hanska and her companions in Dresden, from where they set off for a month-long stay at the waters of Cannstadt near Stuttgart and a trip on the Rhine to Strasbourg, ending on July 9. The trip had been very pleasant. Balzac and his friends, having seen in Cologne a performance of Les Saltimbanques, a three-act parade by Dumersan and Varin, had the idea of distributing among themselves the roles that had made them laugh. Balzac had become the troupe’s compère under the name of Bilboquet, Madame Hanska was Atala, the heroine for whom Bilboquet sighed, while Georges and Anna were two charming comparses, Zéphirine and Gringalet. The troupe had done a lot of wandering, indulging in the temptations and satisfactions of bric-a-brac. On his return to Paris, Balzac was accompanied by Madame Hanska and her daughter, whom he had installed in a small apartment in the rue de la Tour. The following weeks saw a long excursion to Touraine and Berry, followed by an expedition to Belgium and Holland. In the end, Balzac did not return to Paris until August 30. But not for long. After leaving Paris for a few days at the end of September for a quick trip to Baden, Balzac set off again at the end of October with the same companions, following them to Naples, from where he returned to Paris. He returned on November 7. This timetable and these working conditions explain why we find in Petites misères de la vie conjugale some traces of haste and even contradictions. Adolphe and Caroline are merely names that avoid the need to write Monsieur and Madame at every turn. Nevertheless, as they are referred to as characters throughout the book, the reader ends up giving them a kind of individuality. So we’re surprised that a couple married for five years, as we’re told in the chapter entitled La Campagne de France, could have thought of putting their child through college, as discussed in an earlier chapter, La Conduite des femmes. This same Adolphe is, incidentally, a character to be transformed. He does business, even bad business in the first part: but in the second part, he has become a writer who occasionally occupies himself with journalism, and who counts as just one of the “utilities” that feature on the literary scene. Caroline is sometimes a petite provincial married at twenty-seven, sometimes a “young person” from the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, a student at the renowned Institution des demoiselles Mâchefer. None of this matters, as the reader accepts the characters from the outset as marital puppets who are only there for show. But it’s significant that Balzac didn’t bother to rectify these easy-to-correct contradictions. The layout of Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale reveals the same casualness. The book is divided into two parts, each preceded by a preface. In one of these prefaces, Balzac explains that the first part is devoted to the little miseries through which husbands learn, while the second part describes the young woman’s disappointments. In reality, the distribution of scenes between the two parties depends on a different classification.

Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale is made up of thirty-five humorous scenes from different periods of Balzac’s output. He presented them by attributing them to two symbolic characters, a husband he called Adolphe, and a young wife he called Caroline. Two of the scenes from this young couple’s married life, one describing a doctor’s visit requested by Madame, who is suffering from vapors, the other recounting Caroline’s misunderstanding of a friendly couple of lovers she saw caressing in the building across the street, are two short articles Balzac had published in La Caricature, a satirical newspaper to which he contributed in 1830. Eleven other scenes had appeared in 1839, under the general title Petites misères de la vie conjugale, in another series of La Caricature called La Caricature non politique. Most of them are placed in the first part of Petites Misères. A third series of ten scenes was finally published in Hetzel’s collective collection Le Diable à Paris in August 1844, under the title Philosophie de la vie conjugale. Most of these scenes also belong to the first part of Petites misères de la vie conjugale. Hetzel was so pleased with the public’s response that he published his articles in an in-12 booklet in 20 issues at 15 centimes, on sale from July to November 1845 under the title Paris marié. It was apparently the success of this operation that gave Balzac the idea of taking it up again in a more extensive form. As early as December 1845, he had a final series of “scenes” published in the daily La Presse, most of which now make up the second part of Petites Misères, thus providing him with the material for a volume. At the same time, Balzac was signing a treatise on the Petites misères de la vie conjugale with one of his new publishers, the Pole Chlendowski, a treatise that did not put an end to his book’s adventures. Indeed, 1845 had been a year of travel and vacations for Balzac. It was one of the happiest years of his life. He devoted part of it to a joyous trek across Europe in the company of Madame Hanska, her daughter Anna and her fiancé, Count Georges Mniszeck. On April 25, 1845, Balzac joined Madame Hanska and her companions in Dresden, from where they set off for a month-long stay at the waters of Cannstadt near Stuttgart and a trip on the Rhine to Strasbourg, ending on July 9. The trip had been very pleasant. Balzac and his friends, having seen in Cologne a performance of Les Saltimbanques, a three-act parade by Dumersan and Varin, had the idea of distributing among themselves the roles that had made them laugh. Balzac had become the troupe’s compère under the name of Bilboquet, Madame Hanska was Atala, the heroine for whom Bilboquet sighed, while Georges and Anna were two charming comparses, Zéphirine and Gringalet. The troupe had done a lot of wandering, indulging in the temptations and satisfactions of bric-a-brac. On his return to Paris, Balzac was accompanied by Madame Hanska and her daughter, whom he had installed in a small apartment in the rue de la Tour. The following weeks saw a long excursion to Touraine and Berry, followed by an expedition to Belgium and Holland. In the end, Balzac did not return to Paris until August 30. But not for long. After leaving Paris for a few days at the end of September for a quick trip to Baden, Balzac set off again at the end of October with the same companions, following them to Naples, from where he returned to Paris. He returned on November 7. This timetable and these working conditions explain why we find in Petites misères de la vie conjugale some traces of haste and even contradictions. Adolphe and Caroline are merely names that avoid the need to write Monsieur and Madame at every turn. Nevertheless, as they are referred to as characters throughout the book, the reader ends up giving them a kind of individuality. So we’re surprised that a couple married for five years, as we’re told in the chapter entitled La Campagne de France, could have thought of putting their child through college, as discussed in an earlier chapter, La Conduite des femmes. This same Adolphe is, incidentally, a character to be transformed. He does business, even bad business in the first part: but in the second part, he has become a writer who occasionally occupies himself with journalism, and who counts as just one of the “utilities” that feature on the literary scene. Caroline is sometimes a petite provincial married at twenty-seven, sometimes a “young person” from the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, a student at the renowned Institution des demoiselles Mâchefer. None of this matters, as the reader accepts the characters from the outset as marital puppets who are only there for show. But it’s significant that Balzac didn’t bother to rectify these easy-to-correct contradictions. The layout of Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale reveals the same casualness. The book is divided into two parts, each preceded by a preface. In one of these prefaces, Balzac explains that the first part is devoted to the little miseries through which husbands learn, while the second part describes the young woman’s disappointments. In reality, the distribution of scenes between the two parties depends on a different classification.

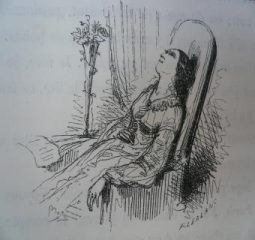

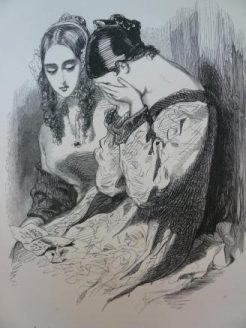

In the first part, Balzac describes the disappointments and misunderstandings that occur in the early years of marriage. Caroline is still young: she’s ignorant, she makes “blunders”, she has naive ambitions as a young bride, she’d like a car, a country house, toiletries that allow her to shine, outings. Setting up the lifestyle thwarted his dreams. But these little frustrations are only about ostentation, they’re only about vanity. In the second part, most of whose chapters come from a later period of writing, the wounds are deeper: the disappointments of sensitivity. Adolphe is no longer as much in love as he was in the early months, he has neither the fortune nor the moral standing we had hoped for, it’s the imagination that has to retreat in the face of reality. The small disappointments of love, the failure of small conjugal cares, the renunciation of the perfect happiness announced by imperceptible symptoms, are wounds more cruel, more profound than the setbacks of vanity. It’s also a time of jealousy, espionage, humiliation and, worst of all, acceptance. We recognize, then, the painter of the “women’s studies”, more attentive, more sensitive than the cheerful journalist of the first part.

In the first part, Balzac describes the disappointments and misunderstandings that occur in the early years of marriage. Caroline is still young: she’s ignorant, she makes “blunders”, she has naive ambitions as a young bride, she’d like a car, a country house, toiletries that allow her to shine, outings. Setting up the lifestyle thwarted his dreams. But these little frustrations are only about ostentation, they’re only about vanity. In the second part, most of whose chapters come from a later period of writing, the wounds are deeper: the disappointments of sensitivity. Adolphe is no longer as much in love as he was in the early months, he has neither the fortune nor the moral standing we had hoped for, it’s the imagination that has to retreat in the face of reality. The small disappointments of love, the failure of small conjugal cares, the renunciation of the perfect happiness announced by imperceptible symptoms, are wounds more cruel, more profound than the setbacks of vanity. It’s also a time of jealousy, espionage, humiliation and, worst of all, acceptance. We recognize, then, the painter of the “women’s studies”, more attentive, more sensitive than the cheerful journalist of the first part.  Is this really the sequel to Physiology of Marriage ? Are Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale applications or illustrations of Physiologie du mariage ? They can be presented as follows. And that’s probably what Balzac meant when he saw them as the “sequel” to Physiologie. But first of all, there is a difference between the two works in the orientation of the lens. The women whose behavior Balzac analyzes in his Physiologie du mariage belong to the aristocracy in their lifestyle, their manners, their situation, their very homes. These are women from “Faubourg Saint-Germain”: in Balzac’s time, a social definition. The symbolic household in Petites Misères faces difficulties never encountered in Physiologie du mariage : their friends, like them, are bourgeois households, their lifestyle, their concerns, their ambitions, their “milieu”, in short, belong to a different social level. These are women from the “Faubourg Saint-Honoré”, a new district inhabited by the nouveau riche, successful bankers and shopkeepers. That’s the first difference. There’s another, just as characteristic. The women in Physiologie are Restoration women, while the dowagers lived through the reign of Louis XVI. The women in Petites Misères are women of Louis-Philippe’s time, belonging to those newcomers who arrive at the frontiers of worldly life, but who are not yet part of that society where we have grandmothers, memories and a past. Visit The little miseries of married life are nothing more than bourgeois satire, while the The physiology of marriage was a reflection on morals presented by a “young bachelor” who was clearly “M. de Balzac”, before becoming “M. le comte de Balzac”.

Is this really the sequel to Physiology of Marriage ? Are Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale applications or illustrations of Physiologie du mariage ? They can be presented as follows. And that’s probably what Balzac meant when he saw them as the “sequel” to Physiologie. But first of all, there is a difference between the two works in the orientation of the lens. The women whose behavior Balzac analyzes in his Physiologie du mariage belong to the aristocracy in their lifestyle, their manners, their situation, their very homes. These are women from “Faubourg Saint-Germain”: in Balzac’s time, a social definition. The symbolic household in Petites Misères faces difficulties never encountered in Physiologie du mariage : their friends, like them, are bourgeois households, their lifestyle, their concerns, their ambitions, their “milieu”, in short, belong to a different social level. These are women from the “Faubourg Saint-Honoré”, a new district inhabited by the nouveau riche, successful bankers and shopkeepers. That’s the first difference. There’s another, just as characteristic. The women in Physiologie are Restoration women, while the dowagers lived through the reign of Louis XVI. The women in Petites Misères are women of Louis-Philippe’s time, belonging to those newcomers who arrive at the frontiers of worldly life, but who are not yet part of that society where we have grandmothers, memories and a past. Visit The little miseries of married life are nothing more than bourgeois satire, while the The physiology of marriage was a reflection on morals presented by a “young bachelor” who was clearly “M. de Balzac”, before becoming “M. le comte de Balzac”.  It is this difference in altitude of observation that makes the difference between Physiologie du mariage and Petites misères de la vie conjugale. In 1830, the reflection on manners was a prologue to La Comédie humaine. It presented the countesses and duchesses of the Scènes de la vie parisienne and, at the same time, the instrument through which we could understand their calculations, their wiles and their lives. Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale, on the other hand, are nothing more than magic lantern views with anecdotal value. They don’t add anything, they don’t demonstrate anything, they’re alien even to the thinking that feeds the whole descriptive system of La Comédie humaine. So we shouldn’t expect to find in Petites misères de la vie conjugale the theses or reflections that merit the Physiologie du mariage the place Balzac gives it in Etudes analytiques. Despite the liveliness and verve of the style, the richness of the “metaphorical creation” – perhaps because of them, as Balzac is a little too keen to “shine” – Pierre Citron has described Les Petites Misères as “desolately easy”. And Per Nykrog, in his study published in Sweden on Balzac’s thoughts in “La Comédie humaine even criticizes Balzac’s publishers for having obeyed the author’s instructions by maintaining among the Analytical studies a work “manifestly alien” to the ideas Balzac considered essential.

It is this difference in altitude of observation that makes the difference between Physiologie du mariage and Petites misères de la vie conjugale. In 1830, the reflection on manners was a prologue to La Comédie humaine. It presented the countesses and duchesses of the Scènes de la vie parisienne and, at the same time, the instrument through which we could understand their calculations, their wiles and their lives. Les Petites misères de la vie conjugale, on the other hand, are nothing more than magic lantern views with anecdotal value. They don’t add anything, they don’t demonstrate anything, they’re alien even to the thinking that feeds the whole descriptive system of La Comédie humaine. So we shouldn’t expect to find in Petites misères de la vie conjugale the theses or reflections that merit the Physiologie du mariage the place Balzac gives it in Etudes analytiques. Despite the liveliness and verve of the style, the richness of the “metaphorical creation” – perhaps because of them, as Balzac is a little too keen to “shine” – Pierre Citron has described Les Petites Misères as “desolately easy”. And Per Nykrog, in his study published in Sweden on Balzac’s thoughts in “La Comédie humaine even criticizes Balzac’s publishers for having obeyed the author’s instructions by maintaining among the Analytical studies a work “manifestly alien” to the ideas Balzac considered essential.

Source analysis: preface, study compiled from the full text of the Comédie Humaine works Humaine published by France Loisirs 1986, under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

No Comments