Physiology of Marriage

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XVIth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Analytical studies

PHYSIOLOGY OF MARRIAGE

DEDICATION Pay attention to these words (page 34): The superior man to whom this book is dedicated ; Aren’t you saying: – It’s yours? THE AUTHOR. Any woman tempted by the title of this book to open it can dispense with it, as she has already read it without knowing it. A man, however malicious he may be, will never say as much good or as much bad about women as they themselves think. If, in spite of this advice, a woman persists in reading the work, delicacy should impose upon her the law of not disparaging the author, since, depriving himself of the approvals that most flatter artists, he has, as it were, engraved on the frontispiece of his book the cautious inscription on the door of some establishments: Ladies don’t come in here.

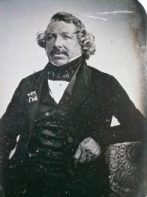

Analysis of the work This volume contains the Physiology of Marriage, an essay published by Balzac in December 1929. with no signature other than the cautious phrase “by a young bachelor”. Despite its anonymity, this essay was Balzac’s first success, transforming an obscure, hard-working littérateur into a celebrated young writer overnight. Because of its character, this essay cannot be classified in either the Etudes de mœurs or the Etudes philosophiques, which only contain short stories or novels. But for the same reason, Balzac gave it a prominent – and solitary – place in a third division of his work, the Etudes analytiques, which was to be the crowning achievement of La Comédie humaine. Unfortunately, Balzac never had the time to write the works that were to take their place in this prestigious series, and Physiologie du mariage is today the only title that can be classified in this division. This clarification is an important element in understanding the meaning of The Physiology of Marriage. Critics mistook it for an impertinent joke. The sarcastic tone of the essay explains this misunderstanding. In fact, when you compare the The physiology of marriage of the other essays that were to appear alongside her in the Analytical studiesIn fact, we’re obliged to consider it as a work whose apparent meaning is “droll”, but whose intentions are far more serious and revealing than this presentation suggests.  The first thing to do, therefore, is to indicate what the program of these Etudes analytiques was to be, and what Balzac’s purpose in announcing them was. In a letter he wrote to Madame Hanska in 1834 to explain the structure of his work, he said: “Les Etudes de mœurs will represent all social effects…the second foundation (will be) Philosophical Studies, because after the effects will come the causes… Then, after the effects and the causes must be sought in the principles. ” This statement is not very clear. However, it is repeated in the famous Foreword that Balzac placed eight years later, in 1842, at the head of the first edition of La Comédie humaine. In this essay, Balzac, a little more explicit, declared, after mentioning the Etudes de mœurs and Etudes philosophiques, “above will be the Etudes analytiques, of which I will say nothing, as only one has been published, the Physiologie du mariage “. The reader is not much better informed. But the following sentence provides a few details: “In the near future, I shall be giving two (sic) more works of this kind: first, Pathology of Social Life, thenAnatomy of Teaching Bodies and Monography of Virtue. “But it does have the merit of teaching us that, to get some idea of these Etudes analytiques , which were never written, we need to refer to what we know of the various essays Balzac intended to include.

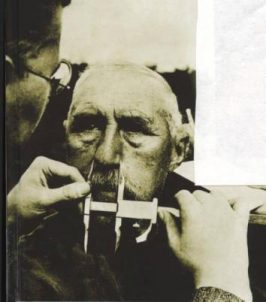

The first thing to do, therefore, is to indicate what the program of these Etudes analytiques was to be, and what Balzac’s purpose in announcing them was. In a letter he wrote to Madame Hanska in 1834 to explain the structure of his work, he said: “Les Etudes de mœurs will represent all social effects…the second foundation (will be) Philosophical Studies, because after the effects will come the causes… Then, after the effects and the causes must be sought in the principles. ” This statement is not very clear. However, it is repeated in the famous Foreword that Balzac placed eight years later, in 1842, at the head of the first edition of La Comédie humaine. In this essay, Balzac, a little more explicit, declared, after mentioning the Etudes de mœurs and Etudes philosophiques, “above will be the Etudes analytiques, of which I will say nothing, as only one has been published, the Physiologie du mariage “. The reader is not much better informed. But the following sentence provides a few details: “In the near future, I shall be giving two (sic) more works of this kind: first, Pathology of Social Life, thenAnatomy of Teaching Bodies and Monography of Virtue. “But it does have the merit of teaching us that, to get some idea of these Etudes analytiques , which were never written, we need to refer to what we know of the various essays Balzac intended to include.  So this report isn’t as disappointing as it might seem. For, by consulting the advertisements Balzac had printed on the covers of his various novels, and also the lists found among his papers, we can first include titles whose details are not given in 1842, but we can even indicate what these singular titles were to contain. As for titles not named in 1842, Balzac specialists agree that Traité de la vie élégante, Théorie de la démarche and Traité des excitants modernes were all published in magazines. These three essays were to form part of the Pathology of Social Life announced in theForeword of 1842. This already gives us an indication of the direction of Balzac’s thinking. As for the two additional titles mentioned in 1842, Balzac’s papers or the indications in his correspondence allow us to imagine, to a certain extent, what their content must have been. Among the essays that were to make up Pathologie de la vie sociale, Théorie de la démarche, as its name suggests, is the continuation and development of the physiognomonic system, to which Balzac often refers in his character portraits. We learn that the information that facial features and expressions give us about someone, we can also obtain or complete by paying attention to gestures, gait and composure. In his Traité de la vie élégante (Treatise on Elegant Life), Balzac describes the influence of others, the pressure of fashion, propriety, conformism and the entire social structure on the behavior of each individual. Lastly, in his Traité des excitants modernes (Treatise on Modern Excitants), in principle devoted to the disadvantages of abusive tobacco and coffee use, Balzac wonders to what extent drugs or vices, which are kinds of drugs, also change what we are. These observations may seem minor, but in reality they are not, for in these three works we find, applied to our social life, some of the ravages or at least the flexions that thought (and by this Balzac meant our ideas, our feelings, our conformism, incitement, customs) exerts in other circumstances on our private life. Information on the other two titles cited in theForeword to La Comédie humaine was provided by Balzac himself, in 1839, in a Preamble at the head of his Traité des excitants modernes. In this Preamble, l’Anatomy of the teaching professionannounced under the titleAnalysis of teaching staffis presented in these terms: “(It) comprises the philosophical examination of everything that influences man before conception, during gestation, after birth, and from birth until the age of twenty-five, when a man is makes. “Balzac was inspired by Sterne’s Tristram Shandy , often quoted in the Physiology of Marriage, on the importance of the parents’ physical dispositions and feelings at the moment of conception. The Preamble warns us that Balzac intends to make use of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’sEmile, which “has not, in this respect, embraced the tenth part of the subject”, and whom he blames for having pushed his contemporaries towards “English hypocrisy”. Balzac obviously encounteredeugenics on this itinerary: and this word alone is enough to evoke the moral and political perspectives of such a subject, which the obscure and apparently inoffensive title of this essay on the health and training of the human animal hardly suggested.

So this report isn’t as disappointing as it might seem. For, by consulting the advertisements Balzac had printed on the covers of his various novels, and also the lists found among his papers, we can first include titles whose details are not given in 1842, but we can even indicate what these singular titles were to contain. As for titles not named in 1842, Balzac specialists agree that Traité de la vie élégante, Théorie de la démarche and Traité des excitants modernes were all published in magazines. These three essays were to form part of the Pathology of Social Life announced in theForeword of 1842. This already gives us an indication of the direction of Balzac’s thinking. As for the two additional titles mentioned in 1842, Balzac’s papers or the indications in his correspondence allow us to imagine, to a certain extent, what their content must have been. Among the essays that were to make up Pathologie de la vie sociale, Théorie de la démarche, as its name suggests, is the continuation and development of the physiognomonic system, to which Balzac often refers in his character portraits. We learn that the information that facial features and expressions give us about someone, we can also obtain or complete by paying attention to gestures, gait and composure. In his Traité de la vie élégante (Treatise on Elegant Life), Balzac describes the influence of others, the pressure of fashion, propriety, conformism and the entire social structure on the behavior of each individual. Lastly, in his Traité des excitants modernes (Treatise on Modern Excitants), in principle devoted to the disadvantages of abusive tobacco and coffee use, Balzac wonders to what extent drugs or vices, which are kinds of drugs, also change what we are. These observations may seem minor, but in reality they are not, for in these three works we find, applied to our social life, some of the ravages or at least the flexions that thought (and by this Balzac meant our ideas, our feelings, our conformism, incitement, customs) exerts in other circumstances on our private life. Information on the other two titles cited in theForeword to La Comédie humaine was provided by Balzac himself, in 1839, in a Preamble at the head of his Traité des excitants modernes. In this Preamble, l’Anatomy of the teaching professionannounced under the titleAnalysis of teaching staffis presented in these terms: “(It) comprises the philosophical examination of everything that influences man before conception, during gestation, after birth, and from birth until the age of twenty-five, when a man is makes. “Balzac was inspired by Sterne’s Tristram Shandy , often quoted in the Physiology of Marriage, on the importance of the parents’ physical dispositions and feelings at the moment of conception. The Preamble warns us that Balzac intends to make use of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’sEmile, which “has not, in this respect, embraced the tenth part of the subject”, and whom he blames for having pushed his contemporaries towards “English hypocrisy”. Balzac obviously encounteredeugenics on this itinerary: and this word alone is enough to evoke the moral and political perspectives of such a subject, which the obscure and apparently inoffensive title of this essay on the health and training of the human animal hardly suggested.

Eugenics :  All the methods used to improve the genetic the genetic heritage of human groups, by limiting the reproduction of individuals carrying unfavorable characteristics, or by promoting the reproduction the reproduction of individuals with traits deemed favorable favorable: theory that advocates such methods. Apart from the fact that it implies a value judgement necessarily debatable on the genetic heritage of individuals, eugenics comes up against the complexity genetic determinism and transmission hereditary physical and mental traits, which makes its foundations questionable scientists and the potential effectiveness of its methods. It has inspired the worst forms of repression and discrimination, particularly in Nazi Germany. Balzac went on to observe that “at twenty-five, men generally get married”, which enabled him to present the Physiology of Marriage as a sequel to theAnatomy of Teaching Bodies. Together, they describe a breeding process that takes the subject from broodmare to breeder. The Pathology of Social Life is then defined by its subtitle: Méditations mathématiques, physiques, chimiques et transcendantes sur les manifestations de la pensée sous toutes ses formes que lui donne l’état social, soit par le vivre et le couvert, etc. ¨ The details given above provide sufficient commentary on this subtitle. Finally, the Monographie de la vertu, “a long-heralded work that will probably be long overdue”, will aim to show “virtue as a plant with many species”, some natural, others artificial. This “botany” of virtue leads Balzac to distinguish, in the behavior of the human being considered as a social product, “laws of moral conscience” that bear no resemblance, he says, to those of “natural conscience”. Thus, the disorders brought about by thought in social life culminate in moral relativism: society, having created a “social man”, which is a deviation from natural man, also engenders a “social morality”, which is a deviation from natural morality.

All the methods used to improve the genetic the genetic heritage of human groups, by limiting the reproduction of individuals carrying unfavorable characteristics, or by promoting the reproduction the reproduction of individuals with traits deemed favorable favorable: theory that advocates such methods. Apart from the fact that it implies a value judgement necessarily debatable on the genetic heritage of individuals, eugenics comes up against the complexity genetic determinism and transmission hereditary physical and mental traits, which makes its foundations questionable scientists and the potential effectiveness of its methods. It has inspired the worst forms of repression and discrimination, particularly in Nazi Germany. Balzac went on to observe that “at twenty-five, men generally get married”, which enabled him to present the Physiology of Marriage as a sequel to theAnatomy of Teaching Bodies. Together, they describe a breeding process that takes the subject from broodmare to breeder. The Pathology of Social Life is then defined by its subtitle: Méditations mathématiques, physiques, chimiques et transcendantes sur les manifestations de la pensée sous toutes ses formes que lui donne l’état social, soit par le vivre et le couvert, etc. ¨ The details given above provide sufficient commentary on this subtitle. Finally, the Monographie de la vertu, “a long-heralded work that will probably be long overdue”, will aim to show “virtue as a plant with many species”, some natural, others artificial. This “botany” of virtue leads Balzac to distinguish, in the behavior of the human being considered as a social product, “laws of moral conscience” that bear no resemblance, he says, to those of “natural conscience”. Thus, the disorders brought about by thought in social life culminate in moral relativism: society, having created a “social man”, which is a deviation from natural man, also engenders a “social morality”, which is a deviation from natural morality.  To Balzac’s projects must be added two titles about which we have no details:Essai sur les forces humaines andHistoire de l’Eglise primitive, which appear to be complements to Etudes philosophiques rather than parts of Etudes analytiques. This inventory shows the importance of the Etudes analytiques and the scope of Balzac’s ambitions for this part of his work. In reality, it’s a question of ordering the consequences and applications of the “ravages of thought” into a “system”, a guiding idea that can serve as a compass when reading the book. The Human Comedy and, for Balzac, a complete system of the distortions imposed on man as a biological creature by the superstructures of social life. So it’s no longer just society that is “nature within nature”, in the admirable words of the 1842Foreword, it’s civilization as a whole that is nature superimposed on nature.

To Balzac’s projects must be added two titles about which we have no details:Essai sur les forces humaines andHistoire de l’Eglise primitive, which appear to be complements to Etudes philosophiques rather than parts of Etudes analytiques. This inventory shows the importance of the Etudes analytiques and the scope of Balzac’s ambitions for this part of his work. In reality, it’s a question of ordering the consequences and applications of the “ravages of thought” into a “system”, a guiding idea that can serve as a compass when reading the book. The Human Comedy and, for Balzac, a complete system of the distortions imposed on man as a biological creature by the superstructures of social life. So it’s no longer just society that is “nature within nature”, in the admirable words of the 1842Foreword, it’s civilization as a whole that is nature superimposed on nature.

How does this differ from the superstructure described by Karl Marx and so often invoked by his followers? This is the crucial one: For Karl Marx, this superstructure is economic, leading to a political distortion, while for Balzac it is moral, leading to a biological distortion. Balzac’s intention in his Etudes analytiques was indeed to “found an anthropology “, as Pierre-Georges Castex puts it, using Balzac’s own vocabulary.

To define this project, the same critic uses this formula: “The elaboration of a science of social man”. Both of these formulations rightly emphasize the “scientific” character that Balzac wanted to give to this conclusion to his work. The system he wanted to set out was a deduction from the physiological thesis he had presented from the very start of his literary life. And Félix Davin was not wrong to write in 1835 in his Introduction to Etudes de mœurs: “When the third part of the work, the Etudes analytiques, comes along, critics will be speechless before one of the most audacious constructions that a single man has dared to undertake.” Taken as a whole, Physiology of Marriage is no longer an impertinent and amusing satire of married life. This is just an appearance. The Physiology of Marriage has a meaning that we must try to decipher. We are all the more invited to this examination as the The physiology of marriage is not an original “idea”, a seductive project glimpsed all of a sudden as a means of piquing the public’s curiosity: on the contrary, it is a project that Balzac had been carrying within himself for several years, a project which, in its latest form, was the culmination of a maturing process. In the Preamble to his Traité des excitants modernes , published in 1839, Balzac explains: “La Physiologie du mariage is my first work, dating from 1820, when it was known to a few friends, who opposed its publication for a long time.  This extraordinary statement is unverifiable, but several other documents attest to the existence of a project whose initial date remains problematic: firstly, the enigmatic date that Balzac inscribed at the end of The Physiology of Marriagefrom 1824-1829, and above all the existence of a pre-original printed version of the first part of the The physiology of marriage printed by Balzac and registered with the Ministry of the Interior in July 1826. So what does Balzac’s date of 1820 mean? No explanation has been found for this mention. Balzac does, however, make one clarification on the first page of the Physionomie du mariage : “At the time when the much younger (author) was studying French law, the word It was a young man’s observation, and in him, as in so many others, like a stone thrown into a lake… However, the author observed in spite of himself…From the primitive and holy fright caused by adultery, and from the observation he had made of it, a tiny thought was born one morning, in which his ideas were formulated. It was a mockery of marriage: two spouses loving each other for the first time after twenty-seven years of marriage.” There’s not a sentence that doesn’t take us back to Balzac’s family. The adulterous son Mme Balzac had had from M. de Margonne, “the child of love”, stubbornly preferred to Honoré, explains the first sentence. The age difference between Balzac’s fifty-year-old father at the time of his marriage and nineteen-year-old Laure Sallambier provides food for thought on the paradoxical nature of such unions. On the other hand, the sudden revelation of the ease of old age is ambiguous: Balzac’s twenty-seven years, if applied to his parents’ marriage in 1797, give us the date 1824, but if applied to Mme de Berny’s marriage in 1793, we find the year 1820. The two dates are a problem. Balzac’s words “s’aimèrent pour la première fois” (they loved for the first time) are hardly in keeping with the age of his father, who was seventy-eight at the time, and the reference to the Berny household is dubious, since Balzac’s relationship with Madame de Berny at the time hardly explains such an allusion to their intimacy. Balzac then interrupts the genesis of his book, adding at this point: “Ce badinage tomba devant une observation magistrale.” There’s a further landmark in the same passage: “L’auteur devint amoureux” (“The author fell in love”), a phrase that takes us back to 1822, the year of his affair with Madame de Berny. The track then disappeared until 1826. Let’s remember from this pre-genesis that the Physiology of Marriage, in its intention and in its observations, owes something to what Balzac was able to guess about his parents’ misunderstanding. We’ll see later that it probably also owes something to the manias and precepts that Bernard-François Balzac, Honoré’s father, had professed throughout his life. The above-mentioned Preamble to the Traité des excitants modernes also contained a singular statement. Traité des excitants modernes was printed after a new edition of Brillat-Savarin’s famous Physiologie du goût . In his Appendix, Balzac defended himself against any talk of imitation, and it was for this reason that he declared that his Physiologie du mariage was an idea he had thought of in his youth. But he adds at this point: “Although printed in 1826, it has not yet appeared.” This sentence, which went unnoticed for a long time, is the starting point for the second episode in the genesis of Physiology of Marriage. This second episode is part of the history of Balzacian studies. In 1918, Marcel Bouteron, who was for a long time the “pope” of Balzacians, noticed at the sale of the works making up Jules Claretie’s library, a volume described by the catalog in these terms:

This extraordinary statement is unverifiable, but several other documents attest to the existence of a project whose initial date remains problematic: firstly, the enigmatic date that Balzac inscribed at the end of The Physiology of Marriagefrom 1824-1829, and above all the existence of a pre-original printed version of the first part of the The physiology of marriage printed by Balzac and registered with the Ministry of the Interior in July 1826. So what does Balzac’s date of 1820 mean? No explanation has been found for this mention. Balzac does, however, make one clarification on the first page of the Physionomie du mariage : “At the time when the much younger (author) was studying French law, the word It was a young man’s observation, and in him, as in so many others, like a stone thrown into a lake… However, the author observed in spite of himself…From the primitive and holy fright caused by adultery, and from the observation he had made of it, a tiny thought was born one morning, in which his ideas were formulated. It was a mockery of marriage: two spouses loving each other for the first time after twenty-seven years of marriage.” There’s not a sentence that doesn’t take us back to Balzac’s family. The adulterous son Mme Balzac had had from M. de Margonne, “the child of love”, stubbornly preferred to Honoré, explains the first sentence. The age difference between Balzac’s fifty-year-old father at the time of his marriage and nineteen-year-old Laure Sallambier provides food for thought on the paradoxical nature of such unions. On the other hand, the sudden revelation of the ease of old age is ambiguous: Balzac’s twenty-seven years, if applied to his parents’ marriage in 1797, give us the date 1824, but if applied to Mme de Berny’s marriage in 1793, we find the year 1820. The two dates are a problem. Balzac’s words “s’aimèrent pour la première fois” (they loved for the first time) are hardly in keeping with the age of his father, who was seventy-eight at the time, and the reference to the Berny household is dubious, since Balzac’s relationship with Madame de Berny at the time hardly explains such an allusion to their intimacy. Balzac then interrupts the genesis of his book, adding at this point: “Ce badinage tomba devant une observation magistrale.” There’s a further landmark in the same passage: “L’auteur devint amoureux” (“The author fell in love”), a phrase that takes us back to 1822, the year of his affair with Madame de Berny. The track then disappeared until 1826. Let’s remember from this pre-genesis that the Physiology of Marriage, in its intention and in its observations, owes something to what Balzac was able to guess about his parents’ misunderstanding. We’ll see later that it probably also owes something to the manias and precepts that Bernard-François Balzac, Honoré’s father, had professed throughout his life. The above-mentioned Preamble to the Traité des excitants modernes also contained a singular statement. Traité des excitants modernes was printed after a new edition of Brillat-Savarin’s famous Physiologie du goût . In his Appendix, Balzac defended himself against any talk of imitation, and it was for this reason that he declared that his Physiologie du mariage was an idea he had thought of in his youth. But he adds at this point: “Although printed in 1826, it has not yet appeared.” This sentence, which went unnoticed for a long time, is the starting point for the second episode in the genesis of Physiology of Marriage. This second episode is part of the history of Balzacian studies. In 1918, Marcel Bouteron, who was for a long time the “pope” of Balzacians, noticed at the sale of the works making up Jules Claretie’s library, a volume described by the catalog in these terms:

“Balzac père, Histoire de la rage, suivie d’observations sur l’économie politique, etc. Tours, Mame 1814…copy from the library of Honoré de Balzac, the author’s son, containing at the end the 123 pages (untitled) of the Physiologie du mariage. “The buyer was Dr. Ledoux-Lebard, a hospital physician. He authorized Marcel Bouteron to examine this copy and take a photograph. Examination of these 123 pages showed that they differed from the original edition of the Physiology of Marriage in text, typography and chapter order. They could not therefore be proofs of the 1829 edition. Marcel Bouteron found that these were in fact pulled and even rolled sheets, indicating the existence of a pre-original print run of an early version of the Physiologie du mariage, and at the same time suggesting that there may be other copies in existence, which to date have not been found. This pre-original of Physiologie du mariage was published by Maurice Bardèche in 1940, based on the photographic document executed by Marcel Bouteron, then reprinted in 1953 by Moïse Le Yaouanc and in 1973 by Jean Ducourneau. The composition of this pre-original edition had been one of the first works to come out of Balzac’s printing works on rue des Marais Saint-Germain (now rue Visconti): Bernard Guyon found the printer’s declaration filed by Balzac in July 1826, describing the volume as an in-8° of “around 20 leaves”, i.e. 160 pages, “printed in a thousand copies”. This pre-original edition offers at least two problems. The first is the date. Why is there a contradiction between the date 1824-1829 written by Balzac at the end of the The physiology of marriage and the date of 1826, which he does not mention and which is attested to both by the documents and by Balzac’s statement in the Preamble at A treatise on modern excitants ? The second is suggested by the only copy we know of: why did this copy, from Balzac’s library, bring together in the same binding two works as different as theHistory of rabies augmented by a number of other publications by his father, and this version of his The physiology of marriage ? A Balzacian, Albert Prioult, has provided some answers to the first question. Based on a few allusions to contemporary events, he believes that at least part of the work could have been written in 1824. These comparisons are not decisive, but they do lead us to accept that it’s likely that the writing began in 1824, as confirmed by the date written by Balzac himself. The second question is more difficult to answer. Whether Balzac himself or his father was responsible for bringing theHistoire de la rage and the Physiologie du mariage together in a single binding, such a presentation implies either a tribute or a claim: in any case, a kinship. Yet the influence of Balzac’s father’s ideas and idiosyncrasies is so palpable in Physiologie that it suggests at least a collusion. Balzac’s Rousseauism, so evident in his essay, is a paternal legacy. Balzac’s ideas on longevity, on the economy of vital forces and on dietetics were preoccupations of his father, who had taken a share in the Lafarge tontine in the hope of being, thanks to his prudence, the last surviving shareholder. Finally, the taste for gossip, anecdotes and jokes about husbands’ misfortunes are further paternal traits revealed by family correspondence, to which we can add theses inspired by Sterne’s on procreation.

“Balzac père, Histoire de la rage, suivie d’observations sur l’économie politique, etc. Tours, Mame 1814…copy from the library of Honoré de Balzac, the author’s son, containing at the end the 123 pages (untitled) of the Physiologie du mariage. “The buyer was Dr. Ledoux-Lebard, a hospital physician. He authorized Marcel Bouteron to examine this copy and take a photograph. Examination of these 123 pages showed that they differed from the original edition of the Physiology of Marriage in text, typography and chapter order. They could not therefore be proofs of the 1829 edition. Marcel Bouteron found that these were in fact pulled and even rolled sheets, indicating the existence of a pre-original print run of an early version of the Physiologie du mariage, and at the same time suggesting that there may be other copies in existence, which to date have not been found. This pre-original of Physiologie du mariage was published by Maurice Bardèche in 1940, based on the photographic document executed by Marcel Bouteron, then reprinted in 1953 by Moïse Le Yaouanc and in 1973 by Jean Ducourneau. The composition of this pre-original edition had been one of the first works to come out of Balzac’s printing works on rue des Marais Saint-Germain (now rue Visconti): Bernard Guyon found the printer’s declaration filed by Balzac in July 1826, describing the volume as an in-8° of “around 20 leaves”, i.e. 160 pages, “printed in a thousand copies”. This pre-original edition offers at least two problems. The first is the date. Why is there a contradiction between the date 1824-1829 written by Balzac at the end of the The physiology of marriage and the date of 1826, which he does not mention and which is attested to both by the documents and by Balzac’s statement in the Preamble at A treatise on modern excitants ? The second is suggested by the only copy we know of: why did this copy, from Balzac’s library, bring together in the same binding two works as different as theHistory of rabies augmented by a number of other publications by his father, and this version of his The physiology of marriage ? A Balzacian, Albert Prioult, has provided some answers to the first question. Based on a few allusions to contemporary events, he believes that at least part of the work could have been written in 1824. These comparisons are not decisive, but they do lead us to accept that it’s likely that the writing began in 1824, as confirmed by the date written by Balzac himself. The second question is more difficult to answer. Whether Balzac himself or his father was responsible for bringing theHistoire de la rage and the Physiologie du mariage together in a single binding, such a presentation implies either a tribute or a claim: in any case, a kinship. Yet the influence of Balzac’s father’s ideas and idiosyncrasies is so palpable in Physiologie that it suggests at least a collusion. Balzac’s Rousseauism, so evident in his essay, is a paternal legacy. Balzac’s ideas on longevity, on the economy of vital forces and on dietetics were preoccupations of his father, who had taken a share in the Lafarge tontine in the hope of being, thanks to his prudence, the last surviving shareholder. Finally, the taste for gossip, anecdotes and jokes about husbands’ misfortunes are further paternal traits revealed by family correspondence, to which we can add theses inspired by Sterne’s on procreation.  Whether old Bernard-François spiritually claimed his debt by making the Physiologie du mariage a natural sequel to theHistoire de la rage , or whether Balzac failed to recognize it, the point is the same. The father, hardened by unhappy campaigns, and the son, informed by Mme de Berny’s misfortunes, must have been at least accomplices when they chatted amongst themselves about the subjects Balzac dealt with in his essay. The text of the pre-original Physiology of Marriage printed in 1826 comprised 13 meditations, and Balzac’s allusions to them indicate that they were to be divided into four parts. The text of Physiology of Marriage in 1829 comprises 30 meditations in three parts. The 13 meditations of 1826 are divided between the first part of the 1829 edition, entitled Considérations générales, and the second part, entitled Des moyens occultes de défense intérieure et extérieure. The 1826 text is roughly half the size of the 1829 text. From Balzac’s allusions in the 1826 text, we can conclude that he had the four-part plan in mind. This raises the question of whether a second half had already been written in manuscript. This is a hypothesis put forward by René Guise, who considers it “likely” that Balzac had a “complete manuscript” drawn up in 1824 and 1825, of which he could only have composed the first half in 1826. This hypothesis raises a difficulty: why does Balzac describe in his printer’s declaration a work of 10 leaves, which is the extent of the volume composed in 1826, if he had at his disposal a manuscript twice as large? For the time being, what the documents show us is the first half of the The physiology of marriageThe first half, printed in 1826, consists of generalities and an enumeration of the precautions a husband should take, followed by a second half, which appeared in 1829, in which the ups and downs of the first secret and then overt struggle between a wife and her husband are dramatized.

Whether old Bernard-François spiritually claimed his debt by making the Physiologie du mariage a natural sequel to theHistoire de la rage , or whether Balzac failed to recognize it, the point is the same. The father, hardened by unhappy campaigns, and the son, informed by Mme de Berny’s misfortunes, must have been at least accomplices when they chatted amongst themselves about the subjects Balzac dealt with in his essay. The text of the pre-original Physiology of Marriage printed in 1826 comprised 13 meditations, and Balzac’s allusions to them indicate that they were to be divided into four parts. The text of Physiology of Marriage in 1829 comprises 30 meditations in three parts. The 13 meditations of 1826 are divided between the first part of the 1829 edition, entitled Considérations générales, and the second part, entitled Des moyens occultes de défense intérieure et extérieure. The 1826 text is roughly half the size of the 1829 text. From Balzac’s allusions in the 1826 text, we can conclude that he had the four-part plan in mind. This raises the question of whether a second half had already been written in manuscript. This is a hypothesis put forward by René Guise, who considers it “likely” that Balzac had a “complete manuscript” drawn up in 1824 and 1825, of which he could only have composed the first half in 1826. This hypothesis raises a difficulty: why does Balzac describe in his printer’s declaration a work of 10 leaves, which is the extent of the volume composed in 1826, if he had at his disposal a manuscript twice as large? For the time being, what the documents show us is the first half of the The physiology of marriageThe first half, printed in 1826, consists of generalities and an enumeration of the precautions a husband should take, followed by a second half, which appeared in 1829, in which the ups and downs of the first secret and then overt struggle between a wife and her husband are dramatized.  The character of each of these two halves of the work is quite different. The first, ready in 1826, is mainly a series of reflections and observations, all denouncing the paradoxical nature of the conjugal system introduced by the legislator; the second is a series of comedies of married life. We’re therefore faced with two successive conceptions of the subject, one abstract and even philosophical about the nature of marriage, the other concrete, anecdotal, scenic, representing how marriage works. These two conceptions correspond to two different sources of inspiration and information. The first is related to the abundant satirical literature on marriage and the criticism of the institution of marriage found in many 18th-century writers. The second is based on personal accounts, memories and “things seen”, whose inspirers we can discover in Balzac’s entourage. On the first itinerary, we find traditional references, fabliaux, medieval storytellers, the author of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, then Rabelais, Boccaccio, Béroalde de Verville, then Brentôme, companions that Balzac would join in the Contes drolatiques of the following years. Apart from Rabelais, Brantôme and Béroalde de Verville, they are not mentioned in the Physiology of Marriage. Further on, we see another wake, that of the light storytellers of the 18th century, Crébillon, Dorat, Mirabeau. More important is the contribution of 18th-century philosophers and essayists, to whom Balzac makes several borrowings. He refers in particular to Diderot for his essay Sur les femmes and for his Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, to Sterne for his Tristram Shandy, which was one of his bedside books, to Rousseau especially for theEmile, and to Chamfort for his Maximes. To these readings we must add two lesser-known texts, English Divorcespublished in Paris in 1821 and 1822, reports of adultery trials by the King’s Bench and the Ecclesiastical Court: “booksays the title, piquant for jurisconsults, useful to husbands in attack, to wives in defense”.and also the discussions of the Conseil d’Etat during the preparation of the Civil Codereported in the Memoirs on the Consulate by Thibaudeau. These are book sources. They were available to Balzac for the manuscript printed in 1826, and they left many traces in the reflections expressed by Balzac in this first part of his essay. The 1829 text reveals very different information. It is rich in anecdotes drawn from the light storytellers of the 18th century, and above all in traits of manners, situations and memories that attest to the presence of well-informed witnesses. Balzac’s biography names these witnesses. By the time he wrote the 1829 version, Balzac had become the lover of the Duchesse d’Abrantès, widow of Marshal Junot Duc d’Abrantès, who lived modestly at Versailles after a princely lifestyle. She had introduced Balzac to some of her “belles” who had shone during the Directoire period, such as Countess Merlin, to whom Balzac dedicated one of his short stories, The MaranaMme Hamelin, who had been queen of the “Merveilleuses”, confidante of Talleyrand’s friend Montrond, and friend of General Bonaparte. For Balzac, it was a lively repertory of the gallant adventures of the Directoire and Empire periods. His old friend Louis-Philippe de Villers-La Faye, who lived in l’Isle-Adam where Balzac used to visit him in the “Pierrotin carriage” described in Un Début dans la vie, had completed his education and, above all, prepared him to understand the spirit of the times. He had been Master of the Oratory for the Comte d’Artois from 1782 to 1790, and was well acquainted with the court of King Louis XVI and the years following the Revolution. He died in 1822, and was Balzac’s teacher only for the pre-original version of Physiologie. It is generally believed that it was he whom Balzac discreetly staged under the name of M. de Nocé. These sources of information should warn us. What Balzac got to know through him was the very free society of Louis XVI’s reign, and the equally free mores of the Directoire and Empire. One wonders whether his image of women and marriage corresponds to the mentality and life of women under the Restoration. Stendhal, a good witness, pointed out, on the contrary, the prudery that reigned under the reign of Louis XVIII, the affectation of piety and modesty of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, the influence of the priests of the Congregation, the crowds at the masses of Saint-Thomas-d’Aquin.

The character of each of these two halves of the work is quite different. The first, ready in 1826, is mainly a series of reflections and observations, all denouncing the paradoxical nature of the conjugal system introduced by the legislator; the second is a series of comedies of married life. We’re therefore faced with two successive conceptions of the subject, one abstract and even philosophical about the nature of marriage, the other concrete, anecdotal, scenic, representing how marriage works. These two conceptions correspond to two different sources of inspiration and information. The first is related to the abundant satirical literature on marriage and the criticism of the institution of marriage found in many 18th-century writers. The second is based on personal accounts, memories and “things seen”, whose inspirers we can discover in Balzac’s entourage. On the first itinerary, we find traditional references, fabliaux, medieval storytellers, the author of the Cent Nouvelles nouvelles, then Rabelais, Boccaccio, Béroalde de Verville, then Brentôme, companions that Balzac would join in the Contes drolatiques of the following years. Apart from Rabelais, Brantôme and Béroalde de Verville, they are not mentioned in the Physiology of Marriage. Further on, we see another wake, that of the light storytellers of the 18th century, Crébillon, Dorat, Mirabeau. More important is the contribution of 18th-century philosophers and essayists, to whom Balzac makes several borrowings. He refers in particular to Diderot for his essay Sur les femmes and for his Supplément au voyage de Bougainville, to Sterne for his Tristram Shandy, which was one of his bedside books, to Rousseau especially for theEmile, and to Chamfort for his Maximes. To these readings we must add two lesser-known texts, English Divorcespublished in Paris in 1821 and 1822, reports of adultery trials by the King’s Bench and the Ecclesiastical Court: “booksays the title, piquant for jurisconsults, useful to husbands in attack, to wives in defense”.and also the discussions of the Conseil d’Etat during the preparation of the Civil Codereported in the Memoirs on the Consulate by Thibaudeau. These are book sources. They were available to Balzac for the manuscript printed in 1826, and they left many traces in the reflections expressed by Balzac in this first part of his essay. The 1829 text reveals very different information. It is rich in anecdotes drawn from the light storytellers of the 18th century, and above all in traits of manners, situations and memories that attest to the presence of well-informed witnesses. Balzac’s biography names these witnesses. By the time he wrote the 1829 version, Balzac had become the lover of the Duchesse d’Abrantès, widow of Marshal Junot Duc d’Abrantès, who lived modestly at Versailles after a princely lifestyle. She had introduced Balzac to some of her “belles” who had shone during the Directoire period, such as Countess Merlin, to whom Balzac dedicated one of his short stories, The MaranaMme Hamelin, who had been queen of the “Merveilleuses”, confidante of Talleyrand’s friend Montrond, and friend of General Bonaparte. For Balzac, it was a lively repertory of the gallant adventures of the Directoire and Empire periods. His old friend Louis-Philippe de Villers-La Faye, who lived in l’Isle-Adam where Balzac used to visit him in the “Pierrotin carriage” described in Un Début dans la vie, had completed his education and, above all, prepared him to understand the spirit of the times. He had been Master of the Oratory for the Comte d’Artois from 1782 to 1790, and was well acquainted with the court of King Louis XVI and the years following the Revolution. He died in 1822, and was Balzac’s teacher only for the pre-original version of Physiologie. It is generally believed that it was he whom Balzac discreetly staged under the name of M. de Nocé. These sources of information should warn us. What Balzac got to know through him was the very free society of Louis XVI’s reign, and the equally free mores of the Directoire and Empire. One wonders whether his image of women and marriage corresponds to the mentality and life of women under the Restoration. Stendhal, a good witness, pointed out, on the contrary, the prudery that reigned under the reign of Louis XVIII, the affectation of piety and modesty of the Faubourg Saint-Germain, the influence of the priests of the Congregation, the crowds at the masses of Saint-Thomas-d’Aquin.

George Sand

What we can guess from what he says about the young countesses of this period hardly corresponds to the intrigues and Scapin tricks that Balzac so readily describes in Physiologie du mariage. This survey highlights the ambiguous nature of Physiology of Marriage. Not only is the author’s image of the woman out of step with the woman of the Restoration, it is also arbitrary, due to Balzac’s definition of the “proper woman”. As in many of the short stories of the period, and in most of his articles in worldly journals, Balzac stipulates for couples who belong to a very limited milieu, that of the “Tout-Paris”. Not all husbands live in a mansion between courtyard and garden, guarded by a doorman, and not all wives live in perfumed idleness, awaiting the visit of handsome bachelors. For whom is Balzac speaking when he describes these childless women, these couples who are never a family, this false life that ignores the simple loyalty of affection and even life as it is, with its joys, its worries and its suffering? Is married life necessarily a struggle between the husband’s selfishness and the wife’s selfishness, a kriegspiel in which cunning meets perfidy? The Physiology of Marriage is constantly hampered by this false, narrowing perspective. The alert, biting scenes, the humor, the lively style and the insight don’t succeed in making us forget that these couples are strangers to us because they are “untraceable” and their tête-à-tête is of no interest to us. It’s a pity, because Balzac’s analysis of the institution of marriage is vigorous and accurate, and because the essay is entirely informed and nourished by the reflections he draws from the system that is taking shape  which found its first expression in the Physiology of Marriage. It’s this gift for analysis that we first appreciate. The anomaly of women’s condition in marriage at the time is well seen and strongly expressed in phrases that Balzac ironically tempers with the vigor of his definitions “Let woman be treated as a slave…(She) is property acquired by contract acquired by contract, she is movable, because possession is equivalent to title, and she is, strictly speaking, only an appendage of man.” The presentation is sarcastic, but the deductions inspire the whole book. This “enslaved queen” aspires to free herself from marital despotism. His weapons in this reconquest are hypocrisy and cunning. If she succeeds, she imposes her will on the tyrant; if she fails, she punishes him in her own way. The story of a household is the story of a struggle between two powers. The husband counters with Machiavellianism and the precautions or stratagems of power. All this is true in substance, and false in the caricatured optics that humor demands. This transposition is a spice that makes for fun reading: all married life is that at heart, but isn’t in reality; trust, loyalty and affection change everything. In this portrait of women, Balzac seems misogynistic. He portrays it as a sneaky, dangerous animal. In fact, he pleads for her. In her eyes, she’s the victim of a bad lifestyle and oppressive legislation. Balzac defends her while seeming to advise his tyrant. This is evident in the program he proposes to amend the institution he so cruelly portrays. Here, his proposals are as modern as his painting of marriage is anachronistic. Taking up Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thesis in Emile ou De l’éducationIn this regard, he relies on his axiom: “Among peoples with morals, girls are easy and women strict; the opposite is true among those without. He develops this thought by wishing for what Stendhal had already called for: “There is only one way to obtain more fidelity from women in marriage, and that is to give freedom to young girls and divorce to married people.” Accepting the consequences of this attitude, Balzac accepted the revolutionary idea of “trial marriage”. With Mirabeau, he affirms: “A marriage cemented under the auspices of the religious scrutiny that love presupposes, and under the empire of the disenchantment that possession follows, must be the most indissoluble of all unions.” And, going further himself than any of the authorities he cautiously surrounds himself with, he doesn’t hesitate to designate as “the silliest of all prejudices” the one his contemporaries adopt on the virginity of girls. It was the book’s light-hearted tone that helped to convey these more serious truths.

which found its first expression in the Physiology of Marriage. It’s this gift for analysis that we first appreciate. The anomaly of women’s condition in marriage at the time is well seen and strongly expressed in phrases that Balzac ironically tempers with the vigor of his definitions “Let woman be treated as a slave…(She) is property acquired by contract acquired by contract, she is movable, because possession is equivalent to title, and she is, strictly speaking, only an appendage of man.” The presentation is sarcastic, but the deductions inspire the whole book. This “enslaved queen” aspires to free herself from marital despotism. His weapons in this reconquest are hypocrisy and cunning. If she succeeds, she imposes her will on the tyrant; if she fails, she punishes him in her own way. The story of a household is the story of a struggle between two powers. The husband counters with Machiavellianism and the precautions or stratagems of power. All this is true in substance, and false in the caricatured optics that humor demands. This transposition is a spice that makes for fun reading: all married life is that at heart, but isn’t in reality; trust, loyalty and affection change everything. In this portrait of women, Balzac seems misogynistic. He portrays it as a sneaky, dangerous animal. In fact, he pleads for her. In her eyes, she’s the victim of a bad lifestyle and oppressive legislation. Balzac defends her while seeming to advise his tyrant. This is evident in the program he proposes to amend the institution he so cruelly portrays. Here, his proposals are as modern as his painting of marriage is anachronistic. Taking up Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s thesis in Emile ou De l’éducationIn this regard, he relies on his axiom: “Among peoples with morals, girls are easy and women strict; the opposite is true among those without. He develops this thought by wishing for what Stendhal had already called for: “There is only one way to obtain more fidelity from women in marriage, and that is to give freedom to young girls and divorce to married people.” Accepting the consequences of this attitude, Balzac accepted the revolutionary idea of “trial marriage”. With Mirabeau, he affirms: “A marriage cemented under the auspices of the religious scrutiny that love presupposes, and under the empire of the disenchantment that possession follows, must be the most indissoluble of all unions.” And, going further himself than any of the authorities he cautiously surrounds himself with, he doesn’t hesitate to designate as “the silliest of all prejudices” the one his contemporaries adopt on the virginity of girls. It was the book’s light-hearted tone that helped to convey these more serious truths.  Equally interesting are the pages in Physiologie du mariage where we first see the ideas that Balzac would take up a few years later in Louis Lambert and Les Martyrs ignorés. They are all the more characteristic because they are not essential to the subject. In a digression on the unexpected effects of rain or fine weather, Balzac evokes man’s power to “project his will” around him like “a veritable atmosphere”. He goes on to explain: “Man has a given amount of energy: the quantity of energy or will that each of us possesses unfolds like sound, sometimes weak, sometimes strong… It rushes to where man calls it. A boxer spends it in punches, the poet in an exaltation that absorbs and demands an enormous quantity of it, the dancer puts it into his feet, finally everyone distributes it according to his whim.” In a further incision, he mentions “the sharp, cutting action exerted by certain ideas on human organizations”. And it’s in a commentary on modesty that he declares: “The study of the mysteries of thought, the discovery of the organs of thesoul the geometry of its forces, the phenomena of its power, the appreciation of the faculty which it seems to us to possess of moving independently of the body, of transporting itself where it wants and of seeing without the help of its bodily organs, finally the laws of its dynamics and those of its physical influence will constitute the glorious share of the next century in the treasure of the human sciences”. He adds: “This admirable science has already led the Phillips and other skilled physiologists to the discovery of nervous fluid and its circulation. We need to pay close attention to all these terms: each of the expressions in Balzac’s vocabulary here foreshadows the theses that would later be developed by Balzac in the summary of the Traité de la volonté attributed to Louis Lambert. This double bottom of the The physiology of marriage reveals that the pleasant scenes Balzac amuses himself with describing, that his cynicism and sarcasm are only the disguise of a serious reflection not only on morals, but on the unknown physiological springs that intervene like a personal coefficient in all human actions.

Equally interesting are the pages in Physiologie du mariage where we first see the ideas that Balzac would take up a few years later in Louis Lambert and Les Martyrs ignorés. They are all the more characteristic because they are not essential to the subject. In a digression on the unexpected effects of rain or fine weather, Balzac evokes man’s power to “project his will” around him like “a veritable atmosphere”. He goes on to explain: “Man has a given amount of energy: the quantity of energy or will that each of us possesses unfolds like sound, sometimes weak, sometimes strong… It rushes to where man calls it. A boxer spends it in punches, the poet in an exaltation that absorbs and demands an enormous quantity of it, the dancer puts it into his feet, finally everyone distributes it according to his whim.” In a further incision, he mentions “the sharp, cutting action exerted by certain ideas on human organizations”. And it’s in a commentary on modesty that he declares: “The study of the mysteries of thought, the discovery of the organs of thesoul the geometry of its forces, the phenomena of its power, the appreciation of the faculty which it seems to us to possess of moving independently of the body, of transporting itself where it wants and of seeing without the help of its bodily organs, finally the laws of its dynamics and those of its physical influence will constitute the glorious share of the next century in the treasure of the human sciences”. He adds: “This admirable science has already led the Phillips and other skilled physiologists to the discovery of nervous fluid and its circulation. We need to pay close attention to all these terms: each of the expressions in Balzac’s vocabulary here foreshadows the theses that would later be developed by Balzac in the summary of the Traité de la volonté attributed to Louis Lambert. This double bottom of the The physiology of marriage reveals that the pleasant scenes Balzac amuses himself with describing, that his cynicism and sarcasm are only the disguise of a serious reflection not only on morals, but on the unknown physiological springs that intervene like a personal coefficient in all human actions.  This already characteristic reflection, on the one hand, on the collective behavior that each era accepts as habitual, as mores, in the etymological sense of the term, and on the other hand, on the personal behavior that reveals secret forces, more or less numbed or aggressive in each individual, already contains the seeds of the overall study that Balzac would undertake shortly afterwards: it is in this capacity that the Physiology of Marriage may deserve its place among the Analytical Studies.

This already characteristic reflection, on the one hand, on the collective behavior that each era accepts as habitual, as mores, in the etymological sense of the term, and on the other hand, on the personal behavior that reveals secret forces, more or less numbed or aggressive in each individual, already contains the seeds of the overall study that Balzac would undertake shortly afterwards: it is in this capacity that the Physiology of Marriage may deserve its place among the Analytical Studies.

Source analysis: Preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (tome XXVI) published by France Loisirs 1988 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

No Comments