Pierrette

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Fifth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Scenes from provincial life

PIERRETTE – Novel published in the liberal newspaper Le Siècle

Novel dedicated by H. de Balzac to Mademoiselle Anna de Hanska, daughter of Countess Hanska, then aged 11.

TO MADEMOISELLE ANNA DE HANSKA Dear child, you are the joy of a whole house, you whose white or pink cape flutters in summer in the beds of Wierzchownia like a will-o’-the-wisp that your mother and father follow with a tender eye, how am I going to dedicate a story full of melancholy to you? Shouldn’t we tell you about the misfortunes that a young girl as adored as you are will never know, because your lovely hands will one day be able to console them? It’s so difficult, Anna, to find for you, in the history of our mores, an adventure worthy of passing before your eyes, that the author didn’t have to choose; but perhaps you’ll learn how happy you are by reading the one sent to you. Your old friend, De Balzac.

Analysis of the work This novel is part of the Etudes de mœurs in La Comédie humaine, and forms part of the second volume of Scènes de la vie de province, a subset of which is entitled Les Célibataires. First published: January 1840, as a serial in Le Siècle, then in September of the same year. Pierrette is a typical “scene from provincial life”. The city isn’t blurred, reduced to extras: it’s the main actor. The apparent subject is the story of a little orphan girl called Pierrette. The real subject is the story of a small town on the eve of the 1830 revolution. Eugénie Grandet is, in fact, a “scene from private life” set in the provinces. Pierrette is a “scene from provincial life” that is already a “scene from political life”. This is a fairly short novel written by H. de Balzac in the last months of 1839. The story was published in January 1840. This date is no coincidence. Indeed, in 1839 Balzac had just published Béatrix, the first part of which is a magnificent poem about Brittany. And during the summer of 1839, he devoted all his time to trying to save the notary Peytel, condemned to death by the Bourg Court. Balzac had known Peytel, then a journalist with La Caricature – In 1830, Peytel, who had become a notary in Belley, was accused of murdering his wife, perhaps out of jealousy, in circumstances that remained obscure. He had been sentenced to death. Balzac was convinced of his innocence. He left immediately for Bourg with Gavarni to try to save him. He failed: Peytel, 18 years earlier, had made a mockery of bourgeois royalty; his appeal for mercy was rejected. This double encounter determined the meaning of the novel. Brittany will provide Pierrette‘s sentimental fund. The Bretons, Pierrette and her little fiancé Brigaut, are, as in Béatrix, the pure, noble hearts who are the victims; the Peytel trial will provide the intrigue, the judicial comedy, the dramatic material. In June 1839, Balzac’s intention was to write a work that would be “a bit girlish”, intended for Madame Hanska’s daughter Anna, who had just turned eleven. Everything changes after the trip to Bourg and the tragic outcome of the Peytel trial. Pierrette Balzac ends his novel by comparing Pierrette’s death to the unfortunate fate of Beatrice Cenci, whom the Pope had once abandoned to her judges, who had been led astray by political intrigue and family interests. The story of a poor little orphan girl entrusted to the care of imbecilic collaterals who make her a martyr and a whipping boy, the little story told to Anna Hanska, is loaded with meaning. And the setting, the backstage, the accusation, is for readers of La Comédie humaine. The provincial setting, the kinship, the distribution of power among a few bourgeois families, this is the mechanism we find a year later in Ursule Mirouët, and then in Les Paysans: but in Pierrette, it serves no purpose. Because political ferment, when the Villèle ministry resigned, created a counter-power. This decisive year is the one in which Balzac sets the action of the novel. The birth of the protest set up two camps with equal weapons. This is the set-up we find in other Scènes de la vie de province, such as La Rabouilleuse, Le Cabinet des antiques and La Vieille fille. This device provides the dramatic system. But the study of life in the provinces is also a psychological study that brings other factors into play. Eugénie Grandet showed the effects of immobility: this immobility polished the granite of characters, but did not destroy them. In Pierrette, the monotony and narrowness of provincial life have another result: they’re moronic. All they do is complete the destruction begun in Paris by the mechanics of small-scale commerce. This pair of morons is admirable. Sylvie Rogron’s large, sallow face is, along with La Cousine Bette, one of Balzac’s most frightening portraits. The husband sucks. The couple’s first treatment is comic. Their main concern is to decorate the house where they will spend their retirement years, to make it a bourgeois, even wealthy home: this ridiculous, overloaded dwelling is a fine demonstration of the idea dear to Balzac that a dwelling already tells us everything about the person who lives in it. The burghers of Provins laugh at their house and their pretensions. Their grudge of wounded vanity is first and foremost their only feeling. Then comes Balzac’s astonishing “montage” of this grudge, grafting it onto the bitterness of the liberal opposition. The Rogrons become important. This is the moment when Sylvie’s character unfolds, her meanness, her despotism, her pettiness. Jealousy gets in the way, and with jealousy comes espionage and perfidy. Tragedy and comedy mingle in this conjunction of hatred and ridicule. Balzac’s “montage” leads to drama. But this successful “montage” is also the novel’s weakness. Finally, a contradiction is revealed between the subject and Balzac’s magnification of it. Is the Rogrons’ conduct towards Pierrette really a “moral crime”? No motive. Are they torturers? Not even. They’re selfish, indifferent and mean. Pierrette dies because of them, but where is the premeditation, where is the crime? “Why not the galleys,” their lawyer quipped. Balzac thinks too much about the Peytel trial. He transposed it to Provins: but without succeeding in making it a judicial crime or a crime of private life. Credibility suffers from this pathetic magnification. At the end, we read with astonishment the sentence that likens Pierrette’s destiny to that of Beatrice Cenci. It’s not the same thing to die with a deposit of untreated pus behind the ear as to be driven in a tombereau to the scaffold. A comic incident occurred during the publication of Pierrette. Pierrette was serialized in Le Siècle, a liberal newspaper. The newspaper’s editor was greatly embarrassed, as the liberals were portrayed without indulgence in the novel. Balzac was asked to make a number of detailed changes, which he did. But that wasn’t enough. The newspaper had to apologize to its readers. Eugénie Grandet is a “provincial scene” in which we don’t see the inhabitants of the province. Pierrette is a dramatized “provincial scene” in which the inhabitants are the actors in the drama.

Source analysis: Preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (Tome VIII) published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

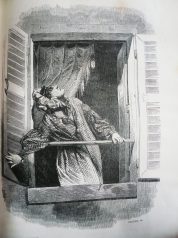

Pierrette and her stepmother

Sylvie Rogron

In this story, Balzac shows us that certain moral crimes in domestic life go unpunished by the law. These hidden crimes remain buried in family secrets – Even today, these offences remain taboo and rarely take the form of legal crimes.

The Story Set at the dawn of the 1830 revolution during the reign of Charles X (1824-1830), the story takes place entirely in the medieval town of Provins in the Seine-et-Marne département. Pierrette Lorrain is a young orphan, entrusted by her bankrupt grandparents to her Rogron cousins, two imbecilic, bitter and selfish bachelors. The passion of these two old bachelors is to refurbish their home, which they bought with their own savings, so that they can enjoy a peaceful retirement. Their sole ambition: to turn the house into a bourgeois residence and rival the salon of the beautiful Madame Typhaine, reputed to be the best place in Provins to spend an evening. The burghers of Provins laugh at their house and their pretensions. Wounded in their pride, they wait for the moment when they become powerful enough to wreak their vengeance. Pierrette, at the center of these rivalries, will be the innocent victim of the manipulations of the characters trying to recover the Rogron fortune. Sylvie Rogron’s wickedness is matched by her despotism, pettiness and jealousy. His jealousy gave rise to espionage and perfidy. Pierrette, who had become their slave, their sufferer, their outlet, dies under the abuse (more moral than physical) of these wicked creatures. The grandmother, alerted by Brigaut, her fiancé, arrives too late. It was Dr. Horace Bianchon who denounced the girl’s abuse and suggested to his master (Desplein) that she be trepanned. Horace assists his master in this delicate operation. Despite the care she received, Pierrette did not survive her injuries. With this novel, Balzac wanted to show the ravages and follies of celibacy. He also points the finger at “the old girls and boys, the drones of the hive”, who are useless and unproductive.

Story sources: 1) Preface – 2 ) Wikipedia.

The characters Pierrette: Daughter of Mr. and Mrs Lorrain. A poor orphan whose ruined maternal grandparents were forced to entrust her to the care of her mother’s brother, née Rogron (her uncle, Old Rogron). Madame Lorrain: Pierrette’s mother – a demoiselle Auffray, from Provins, consanguineous sister (born of a second marriage) of Madame épouse Rogron née Auffray, mother of Sylvine and Jérôme-Denis Rogron. Married at 18 by inclination to a Breton officer named Lorrain in the Imperial Guard. Following the ruin of her mother, Mme Auffray, Mme Lorrain’s share of the estate was reduced to around 8,000 francs. She died 3 years after her mother’s fatal second marriage, in 1819, almost at the same time as her mother. Major Lorrain: Pierrette’s father – Breton officer in the Imperial Guard. Died on the field of honor at Montereau, leaving his widow, aged 21, with a 14-month-old daughter named Pierrette. M.Mme Lorrain: Major’s father and mother, and Pierrette’s paternal grandparents. Wood retailers in Pen-Hoël, a village in the Vendée region known as Le Marais. Pierrette’s guardians on the death of her parents. Aged and no longer fit for business, they were ruined by the shenanigans of an unscrupulous supplier (competitor), and squandered Pierrette’s poor estate. M. Auffray: Pierrette’s grandfather – Married at 18, Monsieur Auffray married a second time at 69. From his first marriage came a rather ugly only daughter, married at the age of 16 to a Provins innkeeper named Rogron. From his second bed, the good man Auffray had yet another charming, easy-on-the-eyes daughter. There was a huge age difference between Monsieur Auffray’s two daughters. The one in the first bed was 50 when the one in the second was born. When her elderly father gave her a sister, Madame Rogron had two adult children. He died at 88, without having had time to make any testamentary dispositions. Mme Auffray (2nd wife): Mme Auffray was 38 when her elderly husband (88) died. She remarried and sold her daughter-in-law (her late husband’s eldest daughter – see below) the land and house she had won under her marriage contract, so that she could marry a young doctor named Néraud, who devoured her fortune. She died of grief and poverty two years later. Pierrette’s aunt: elder daughter of M. Auffray and wife of Rogron, innkeeper. On her father’s death, she and her husband set about maneuvering the estate to their advantage and absorbing most of it. She gave birth to two dreadful children: a daughter Sylvie Rogron and a son Jérôme-Denis Rogron, who (after their paternal grandparents) became Pierrette’s second guardians and torturers.

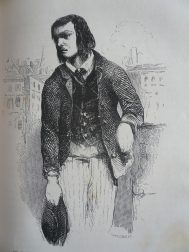

Jacques Brigaut

Jérôme-Denis Rogron’s personality Naïve physiognomy – crushed forehead depressed by fatigue. Short-cut gray hair that makes him look stupid. His little bluish eyes are extinguished. His round, flat face is unsympathetic. The flaccid lividity of people confined to an office. Short, fat body that sags ridiculously. Sylvie Rogron’s personality: An ugly, sour, dry woman who looks like a witch. She adopts a reluctant air and looks older than her years. Small, pale blue eyes, dry and cold. A false smile that plays good-naturedly with the people she comes into contact with, so that they can take her for a good person. Sylvie and Jérôme-Denis Rogron Aunt and Uncle (2ndth degree) of Pierrette. Daughter and son of Mme épouse Rogron (eldest daughter of M. Auffray). Born to innkeeper parents, they were two years apart, and were put up for cheap foster care in the country (old innkeeper Rogron was stingy). The son was then sent to school, and Sylvie was sent to Paris as an apprentice in a haberdashery business at the age of 13. Two years later, his brother was sent down the same road. At 20, Sylvie was second maid to a silk boot merchant. The sister’s story was the brother’s story. Towards the end of 1815, the brother and sister pooled their savings and bought a leading haberdashery retailer. Jacques Brigaut: born around 1811, son of Major Brigaut, a Chouan retired to Pen-Hoël. Jacques started out as a carpenter’s apprentice, then became a soldier after Pierrette’s death. He was Pierrette Lorrain’s childhood friend and became her lover. Mélanie Typhaine: Born Roguin, wife of President Typhaine. “Reine de la ville” (Queen of the town), dominates Legitimist society in Provins. This character reappeared in 1815, in La Vendetta, where she was given the name Mathilde. President Typhaine: Magistrate in Provins, Melanie’s husband, leader of the conservative clan. In the 1826 elections, he beat Vinet by two votes. Horace Bianchon: A doctor, boarder at the Maison Vauquer and member of the Cénacle, he treats many of the characters in La Comédie Humaine. He denounced Pierrette’s mistreatment and tried to save her life, but to no avail. Bathilde de Chargeboeuf: From the poor branch of the Chargeboeuf family. Married J.D. Rogron (father of Sylvie and Jérôme-Denis) to establish herself in Provins, where she became the “beautiful Madame Rogron” and ran her own salon. Eusèbe Gouraud: Retired colonel, survivor of the Beresina, Bonapartist, but linked to the liberal faction in Provins. He had his eye on Sylvie Rogron, and a second career after 1830.

Source for character descriptions:

1) Wikipedia universal encyclopedia;

2) Pierrette by Raymond Mahieu.

No Comments