The Black Sheep

LA COMEDIE HUMAINE – Honoré de Balzac The title “La Rabouilleuse” is represented in the 1877 edition as “Un ménage de garçon” – It appears in the VIth volume of the complete works of H. DE BALZAC by Veuve André HOUSSIAUX, éditeur, Hébert et Cie, Successeurs, 7, rue Perronet, 7 – Paris.

Scenes from provincial life

THE PLANER

Dedicated : TO MONSIEUR CHARLES NODIER Member of the Académie Française Librarian at the Arsenal. Here, my dear Nodier, is a work full of those facts removed from the action of laws by the eight -clos domestique; mais où le doigt de Dieu, si souvent appelé le hasard, supplélé à la justice humaine, et où la morale, pour être dit par un personnage moqueur, n’en fait pas moins instructive et frappant. The result, in my opinion, is some great lessons for both the Family and Motherhood. We may be too late in realizing the effects of reduced paternal authority. This power, which used to cease only with the death of the father, constituted the only human court where were domestic crimes, and on special occasions, Royalty was willing to enforce their judgments. However tender and good a Mother may be, she no more replaces this patriarchal royalty than a Woman replaces a King on the throne; and if this exception occurs, the result is a monstrous being. Perhaps I haven’t drawn a picture that shows more than this one how indispensable indissoluble marriage is to European societies, the misfortunes of feminine weakness, and the dangers of unbridled self-interest. May a society based solely on the power of money shudder when it sees the powerlessness of justice over the combinations of a system that deifies success by pardoning all means! May she soon turn to Catholicism to purify the masses through religious sentiment and education other than that of a secular university. Enough beautiful characters, enough great and noble devotion will shine in the S scenes from Military life, for me to have been allowed to indicate here how much depravity the necessities of war cause in certain minds, which in private life dare to act as on the battlefield. You have cast a sagacious glance at our times, the philosophy of which betrays itself in more than one bitter reflection that pierces through your elegant pages, and you have better than anyone else appreciated the damage done to the spirit of our country by four different political systems. So I couldn’t put this story under the protection of a more competent authority. Perhaps your name will stand for this work against the accusations that are sure to follow: where is the patient who remains mute when the surgeon removes his braces of its most bitter wounds? To the pleasure of dedicating this Scene to you is added the pride of betraying your benevolence for the one who says he is here. One of your sincere admirers, De Balzac.

La Rabouilleuse was originally entitled Un ménage de garçon, which was the title of the novel for a very long time. It’s a bachelor’s study, and it’s for this reason that Balzac classifies it in the subdivision of Scènes de la vie de province that he named: Les célibataires . The isolated male bachelor is prey. La Rabouilleuse tells the story of an attempt to steal an inheritance that had every chance of succeeding, but fails through unforeseen chance. Balzac had been thinking about the subject of capture for a long time. For him, it’s a way of seizing other people’s wealth without having to answer to the courts. As such, capture was part of what he called “hidden crimes”. As early as 1831, he had summarized in his album of subjects one of the plots he intended to use under the title ” The Estate” . It reads: “A nephew attending the show…His ravishing mistress. Uncle in love gives her his fortune. Nephew doesn’t think she’s pretty. Approves of his uncle. Uncle kills himself – he blames him. Uncle dies, mistress and lover marry. Everything had been agreed in a garret. The co-heirs are robbed. It’s not quite the subject of La Rabouilleuse, but it’s a similar situation.

Analysis of the work “La Rabouilleuse” was the nickname of the little girl whom Dr Rouget had taken in, and who became his son Jean-Jacques’s servant-mistress after his death. It has taken hold of the heart and will of the Rouget son, to whom his father left his entire fortune. She has a public affair with a daring scoundrel, Maxence Gilet, whom some people consider to be the natural son of Father Rouget. As such, he intends to appropriate the Rouget family’s assets. Rouget’s heirs, his sister Agathe Bridau and nephew Joseph, who came to Issoudun with the intention of saving part of the inheritance, had to make a pitiful retreat, sullied by a plot Maxence had directed against them. Agathe’s second son Philippe, of the same temperament as Maxence Gilet, is under house arrest by the police, and is persuaded by one of his friends to serve his sentence in Issoudun. It changes the balance of power. Anxious to get his hands on the property he thinks belongs to him, he stirs up his hatred of Maxence and challenges him to a duel. He kills Maxence. Philippe Bridau’s victory forms the core of the second part of this story, which reads like a Western.

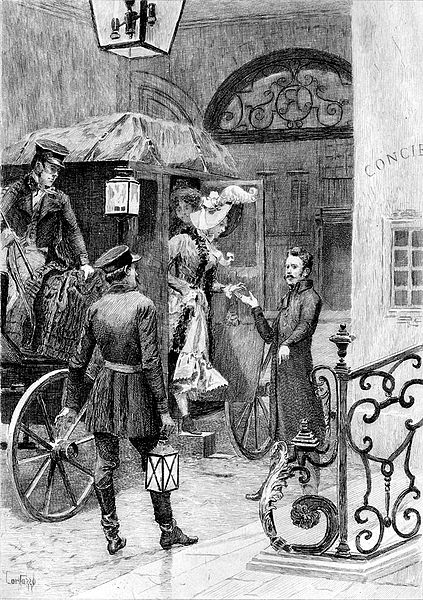

Gémier, actor playing Brideau in La Rabouilleuse

Because of the title and the dramatic nature of the events, we often tend to regard this second part as the heart of the novel. In fact, this is not the case. Balzac wrote his novel in two parts. The first part, set in Paris, appeared in serial form in early 1841: it was called Les deux frères (The Two Brothers). The second part, set in Issoudun, is simply the continuation of the first part, its denouement, and first appeared under the same title, as the end of Les Deux frères. It was only later that the novel was entitled Un ménage de garçon en province, then La Rabouilleuse. The original title should not be overlooked. He designates as the novel’s main subject not the devolution of an inheritance, but a far more troubling and serious opposition: that of good and evil, and a far more atrocious and edifying conclusion, the triumph, in the century, of evil over good: what makes La Rabouilleuse, Balzac’s most sinister and pessimistic novel. It’s all in the causes. If La Rabouilleuse is one of Balzac’s most powerful and cynical novels, it’s because the famous “corsair in yellow gloves”, who appears everywhere in the author’s works and is never fully described anywhere, is here, for the first time, depicted full-length and frightening. Elsewhere, in La Comédie humaine , when we read about Maximes de Trailles or Henry de Marsay, the past of these great condottieri is mentioned. of the 19th century remains obscure: page of the emperor, little scoundrel, we know nothing of Maxime de Traille’s past, only his reputation – and for Henry de Marsay, it’s even worse, his career appears at times like that of a 15th-century Italian adventurer, then we see him at the end president of the council, a myth rather than a character. Philippe Bridau is the first person whose whole life we know: from the moment he was the rascal making his debut. His life is the story of a gangster, the only one Balzac ever told us. Under the guise of saber-rattler and “swaggering soldier”, Philippe hides the depths of his soul and his rebellion in the sound of his boots, as he gambles and drinks his way home empty-handed in the early hours of the morning. All the drama of the story is in the beginning, because all the horror is in learning about evil. Philippe Bridau is a young kingpin: the fault of events and the fault of his mother. From the outset, events gave him an easy success due solely to his courage and the self-image he would never forget: colonel at the age of 22, officer of the Emperor’s order. Then, with the debacle of the fall of the Empire, the anger of being nothing. His mother cultivated this image of perfection in her and in him, and turned it into an idol. It strengthened him in his role as victim. Since he can’t and won’t do anything, and is stubbornly determined not to apply for a position in the Bourbon army, he can only maintain his excessive lifestyle by finding some territory to plunder: he finds it in his family, with his mother’s complicity. He manipulates his mother, his brother and old Descoings, who offer him the same resources as an indulgent mistress. He lives not from women but from the weak. He lives on the adoration of others for him: his mother and old Descoings, and the indulgence of his overly generous brother. It’s a form of pimping. It develops in him an unscrupulous egotism and total cynicism. Everything conspires to make him what Vautrin wanted to make of Rastignac in Le Père Goriot. He has his victims, the post horses abandoned at every relay. It’s his mother, his brother, the Descoings mom. He draws his resources from elegant theft, gambling, suicide threats and all the comedies of his profession. He knows them better than anyone: he lives among theater girls and courtesans. But he lacks that entry card to the world that their birth gives to others, to Maximes de Trailles to de Marsay. His situation is still precarious. He can only play small games, limited by what remains of his family’s resources. At the end of the first part, a defeated man leaves for Issoudun, under house arrest by the Minister of Police for extorting money from his employer’s coffers. He’s a formidable conqueror, because he knows everything about life without ever having sat down to eat. This character embodies the selfishness and cynicism that Balzac so generously attributes to all the triumphers of social life, and it’s his success that makes the second half of the novel so chilling. The Berrichon parsimony and finesse of old Hochon, the senile torpor of Flore’s hold over Rouget, his obsessive submission, Flore Brazier’s audacity, the fear of “qu’en dira t-on”, the gallery of half-soldiers, the mischief and mischief-making of Maxence and his gang with the population – all contribute to form a sleepy landscape, on which the slightest gesture, the slightest event has repercussions, and, like a stone thrown, the slightest step makes a noise. Philippe Bridau needs not the brutality of a marksman, but the caution and speed of a tiger. Philippe Bridau’s triumph is atrocious. In these final pages of the novel, there’s a contempt for social order that Balzac has never surpassed anywhere. Fate strikes too late, its vengeance does not instruct.

History The action is relatively spread out over time, beginning in 1792 with the introduction of the main characters’ father and grandfather, Dr. Rouget, who lives in Issoudun, and ending in 1830. The clever and tyrannical Dr. Rouget took advantage of the French Revolution to enrich himself. What’s more, he married the eldest daughter of the Descoings family, merchants who, like many of the characters in La Comédie Humaine (see Eugénie Grandet), became wealthy through the purchase of national property. When he died in 1805, he left a large fortune almost entirely to his son Jean-Jacques, disinheriting his daughter Agathe, who had emigrated to Paris. She married Bridau, an honest civil servant who devoted his life to Napoleon. On the death of her husband, Agathe Bridau finds herself alone, with few resources to bring up her two children Philippe and Joseph. His financial troubles followed the Napoleonic star. Philippe, a military man at heart, makes his mother happy, while Joseph, the youngest, a future great painter, distresses her. Alas, a good-for-nothing off the battlefield, Philippe refused to serve the Bourbons after Napoleon’s fall. A trip to the United States makes him violent, a gambler, a drinker, a liar and a thief. At the height of their money problems, they learn that their maternal uncle, Jean-Jacques, is in the thrall of a pretty young peasant woman, Flore Brazier, taken in by their father, and who calls herself “la Rabouilleuse” (a person who agitates and muddies the water to scare crayfish and catch them more easily). As Jean-Jacques had no children of his own, Agathe and Joseph went to Issoudun to try to recover part of the fortune they were owed. Because of their naiveté and honesty, they failed and fled Issoudun, Joseph having been falsely accused of attempted murder by Maxence Gilet, the Rabouilleuse’s lover. Philippe, now estranged from his mother, also tries his luck, with more success. He kills Flore’s lover and forces his uncle to marry the Rabouilleuse. His uncle soon died and Philippe married Flore. He kills her through abuse, wear and tear and addiction to Parisian vices. At the head of a considerable fortune, after having been a tramp, he succeeded in the world and changed his name to give himself the title of Count, “Colonel, Count of Brambourg” without giving a penny to save his sick mother. However, he was unable to anticipate political changes and had to leave for Algeria, where he was killed. Father Rouget’s fortune went to Joseph, a well-known artist at the time. Novel written by Honoré de Balzac in Paris in November 1842

The characters Doctor Rouget: a doctor in Issoudun – a cunning, tyrannical man. All his life he nursed a vengeance against his daughter Agathe, whom he never considered his own. Madame Rouget: Doctor Rouget’s wife and the most beautiful woman in Issoudun. A fragile person, she will be tyrannized and under Dr. Rouget’s control. He unjustly suspected her of having had an affair with his close friend, Lousteau, and of giving birth to Agathe, whom he disowned as his daughter. She died as a result of her husband’s decision to get rid of their daughter by sending her to Paris. This slow death was also ensured by her son Jean-Jacques, who, perhaps encouraged by his father, lacked the care and respect a son owes his mother. Jean-Jacques Rouget: Son of Dr. Rouget, who became the main heir to his father’s fortune. Flore Brazier, a self-interested and venal person, becomes Jean-Jacques’ servant-mistress. Agathe Bridau: Jean-Jacques Rouget’s sister and heiress – Jean-Jacques’ youngest daughter by 10 years. Doctor Rouget had always had doubts about his paternity towards Agathe, so he disinherited her in favor of his son Jean-Jacques. Agathe’s birth was the cause of an eternal quarrel between Dr. Rouget and his close friend, the surrogate Lousteau, whom he suspects to be the natural father. Following this quarrel, Lousteau left Issoudun for good, never to return, adding further fuel to the existing rumor mill. Agathe was sent to Paris at an early age to live with her uncle Descoings and her aunt and godmother, Madame Descoings. She married a Bonapartist office manager, Brideau, who gave her two children, Philippe and Joseph, and died of inflammatory fever on the field of honor. An early widow, Agathe will have to exercise not only her role as a mother, but also the power of a father – something few mothers manage to conceive and apply. Philippe Bridau: Eldest son of Agathe Bridau née Rouget. Handsome like his mother but a poor subject like his grandfather, Philippe, a fervent admirer of the Emperor like his father, managed to attend the Lycée Impérial at Saint-Cyr, where he graduated as a second lieutenant in a cavalry regiment. During the French campaign, he became a lieutenant and earned a reputation for his courage in saving his colonel. The Emperor appointed Philippe captain at the battle of La Fère-Champenoise, where he took him on as his orderly officer. Spurred on by such advancement, he won the cross at Montereau. Philippe, a staunch Bonapartist, refused to serve the Bourbons and subsisted on a half-salary of three hundred francs a month. This child, to whom everything seemed to succeed, was the pride and joy of Mrs Bridau, who passed on everything to him. Unoccupied Philippe becomes a drinker, a smoker, a gambler and a violent man. The weaknesses of a loving mother, the selfishness and tyranny of a spoiled, personal, manipulative and insensitive child will gradually kill this mother, as her illusions melt away like snow in the sun. Philippe, a poor subject, manipulates his uncle’s fortune. Now a wealthy man, he changed his name to Count de Brambourg. He left his mother and brother in poverty – he obtained a regiment in Algeria with the hope of becoming a general. Colonel Philippe comte de Brambourg was killed in battle in Algeria, and his fortune passed to his brother Joseph. Joseph Bridau: Youngest son of Agathe Rouget. His passion for painting and the arts disheartened his mother, who always preferred Philippe, an ambitious military man following in his father’s footsteps. Blinded by her love for Philip, she fails to see Philip’s serious shortcomings, and Joseph’s deep, unconditional love for him. She would not see Joseph’s qualities until the end of his life. She’ll feel guilty about it. Sorrow, misery and regret have taken their toll on his beautiful soul. Joseph Bridau became a renowned painter. Mme Descoings: A close friend who calls herself Agathe’s aunt. Retired grocer and pleasant person to live with. Warm and generous, she will share Agathe’s household. Epicurean and gambler, she lost a large fortune and was robbed of her last savings by Philippe Bridau. Flore Brazier: named La Rabouilleuse by Dr. Rouget, who took her in when she was just a little girl. On the doctor’s death, she uses her charms and her hold on the doctor’s son to become his servant, mistress and mistress of the house. Fascinated by Maxence Gilet, she introduces him into Jean-Jacques’ home and lives out her love in full view of the master of the house. The diabolical lovers will not rest until they have manipulated Rouget’s son into appropriating his great fortune. Once Philippe Bridau, Jean-Jacques’ nephew, has killed Maxence, Flore’s lover, he will plot Flore’s marriage to Jean-Jacques (already very old and ill). When his uncle died, he married Flore, whom he tyrannized and mistreated until her death. He will then be the sole heir to the Rougets’ immense fortune; he will change his name and obtain the title of Count. He abandons his mother and brother.

Mrs Jul

Borrowed portrait of Flore Brasier

Maxence Gilet: Notorious Issoudun scoundrel and Flore’s lover. He intends to make Jean-Jacques Rouget’s fortune his own. Philippe, condemned to serve a sentence for misappropriation of corporate assets in exile, managed to get justice done in Issoudun. He challenged Maxence Gilet to a duel and killed him. Monsieur Hochon: Tall, dry, lean with a yellow complexion, stingy, spoke little, read little, observant, never tired, he maintained a highly restrictive regime at home. A man of honor and reason, he will advise Agathe and try in vain with Mme Hochon to see that justice is done so that she can recover part of her inheritance. Madame Hochon: Sister of ex-substitute Lousteau and close friend of Madame Rouget. Madame Hochon is godmother to Agathe, Mme Rouget’s daughter. She tries, unsuccessfully, to help her goddaughter recover part of the inheritance due to her.

Source analysis according to preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (tome IX) published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

History source: Wikipedia, the universal encyclopedia.

No Comments