Lost Illusions (Episode 3) Eve and David

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac Eighth volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1877)

Eve and David Lost Illusions III The inventor’s suffering

Analysis of the work Lucien’s disaster could well have ended the novel. Now Balzac is writing a third episode. And this third episode is so strange that we’re forced to wonder if Lost Illusions is just the story of Lucien de Rubempré, if it isn’t, at the same time, something else. For this three-volume trilogy, published over a period of six years, makes complete sense only through these three episodes. What Balzac wants to show is the ravages that illusions wreak, not only on the one who is the object of them, but on all those who have shared them, and who thus become the victims of the one they were mistaken about. It becomes clear, then, that the novel was indeed begun to illustrate the adventures of the imagination, but those of all imaginations, the generous as well as the childish. The third part, The inventor’s suffering, contains this lesson. The first part ofIllusions perdues describes Eve and David’s illusions about Lucien, and those of Madame de Bargeton. The second part describes Lucien’s illusions about literary life and success, but the third part in no way shows the negative consequences of these illusions; on the contrary, it shows a third illusion just as devastating as the first two, that of the inventor about his invention. The ending, which takes us back to Angoulême and recounts David’s setbacks and the maneuvers of his competitors, the Cointets, to take over his invention, is singular. Balzac is at pains to involve Lucien in this third action, so different from the first two. He does this skilfully, managing to give it a role, but it’s not that of a gas pedal. Finally, this third part, Les souffrances de l’inventeur, delivers on the promise of the title Illusions perdues, teaching that all illusions are unhealthy, even the most generous ones. But in this ending, Lucien de Rubempré is, as it were, absent, as if his fate had already been settled by the author. And, indeed, it was. Even before Balzac had written the second part ofIllusions perdues, Lucien de Rubempré’s disappointments in his Parisian career had been foreseen and defined. This is the most revealing detail in the writing of this trilogy. Balzac dates this second part: “Aux Jardies, December 1838 – Paris, May 1839. However, in September 1838, three months before he began writing A great man from the provinces in ParisBalzac had published The Torpedo, beginning of Splendors and miseries of courtesans in which Lucien de Rubempré, four years after his Parisian disappointment, reappeared at the Opéra ball in the company of a masked stranger, crushing his old rivals with his elegance and aplomb. So Balzac knows all about Lucien’s destiny before he starts telling it. This prescience may not be extraordinary for a novelist, but what is astonishing, and throws a singular light on David, is that Balzac is not mistaken about Lucien. And this prescience gives David’s brotherly friendship a more sentimental nuance: it’s no longer just an illusion, there’s a kind of “white love” on David’s part, a tenderness without ulterior motive but definitely an attraction, which is at the root of his admiration for Lucien. From this point on, there are two threads that cross each other in the Lost illusions. The study of the illusions we have about ourselves and others, and the vanity of which we discover in the end, is a kind ofsentimental education which may have seduced Balzac for a while. Then, very quickly, Rubempré’s destiny became clear to him, and his novel, too, appeared differently. It becomes a kind of proscenium for a much more frightening fate: and, compared to Balzac, a much stranger one. Because at the end, the last-minute twist of fate, the meeting of Lucien, defeated and forced to commit suicide, with this unexpected saviour in whom Balzac readers may recognize Vautrin, the tempter of the Père Goriotthis miraculous twist is not the conclusion ofLost illusions, it’s the preface to another novel. And this other novel, Splendours et misères des courtisanes, will not, like Illusions perdues , be the itinerary of harmless literary arrivisme, but the exploration of a larger, darker cavern, where the great political and financial fortunes of an era are secretly made. But the lesson ofLost Illusions is that all illusions – that is, all imaginative constructs – are dangerous. It’s reality that triumphs. The real winners were the Cointet brothers, who seized David Séchard’s invention and became wealthy paper manufacturers. Eve and David will be happy in the end. But thanks to what? To Father Séchard, who stole his son and planted vines in Marsac. Victory is on the side of reality. In the 19th century, what’s real is money. Today too, for that matter.

Source analysis: preface compiled from the full text of the Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

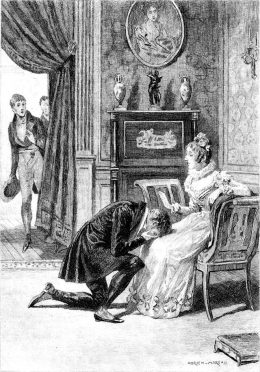

Lucien de Rubempré and Mme de Bargeton

Braulard

The story Ruined and in debt, Lucien returns to Angoulême to his mother, sister Eve and brother-in-law David Séchard. Despite the warmth of the first reunion, Lucien’s inconsistency and the consequences of his behavior towards his family bring him into disrepute. Despite Angoulême’s standing ovation for his poet, and the welcome dinner (hypocritically given) in his honor by his so-called “friends”, including Mme du Châtelet, Lucien realizes that he has lost the esteem and admiration of his family. Eve no longer trusts him. She’s suspicious, and won’t tell him where David is hiding. In fact, David is being prosecuted for a bill of exchange in favor of Lucien (forged by Lucien, who forged his brother-in-law’s signature), the large sum of which is ruining this poor family. Her weaknesses and inconstancy, thus revealed to those who have shown her the most love and trust, are a mortal stab to Lucien’s pride and vanity. In despair, he leaves a letter to his sister, telling her of his intention to commit suicide. Lucien won’t fulfill his doomed destiny, however, as chance has thrown a strange traveler in his path.

Camusot

who claims to be his saviour – but at what price! You’ll discover this when you read the continuation of Lucien’s adventures in Balzac’s Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes. Paris 1835-1843

A detailed description of the characters can be found in the summary of episode I of Lost Illusions.

Source story: Preface compiled from the complete works of the Comédie Humaine (Tome XI) published by France Loisirs 1985 under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac.

No Comments