The Peasants

LA COMEDIE HUMAINE – Honoré de Balzac XVIIIe volume des œuvres complètes de H. DE BALZAC by Veuve André HOUSSIAUX, éditeur, Hébert et Cie, Successeurs, 7, rue Perronet, 7 – Paris (1877)

| Works contained in scenes of country life |

| Scenes from country life : Peasants. The Country Doctor. The village priest. Le Lys dans la vallée |

Scenes from country life

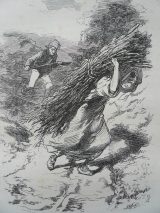

Catherine Tonsard

THE PEASANTS

Analysis of the work Scènes de la vie de campagne is one of three divisions of La Comédie Humaine that Balzac didn’t have time to complete. Like the Scènes de la vie politique and Scènes de la vie militaire, they are a sort of “subdivision” of La Comédie Humaine, with only a small number of completed constructions. One of them is an old one: it’s Le Médecin de campagne (The Country Doctor ), written in 1832. The village priest written in 1839; another is arbitrarily linked to the Scenes from country life it’s Le Lys dans la valléeone of Balzac’s finest and most famous novels, written in 1836 and initially classified as a Scenes from provincial life and the last, the richest and most ambitious, is the great fresco of the Farmers which Balzac never managed to complete in its final form. This collection, which is larger than what has been assembled in the Scènes de la vie militaire and Scènes de la vie politique, needed to be completed. We know Balzac’s intentions. He had entrusted them to the journalist Amédée Achard for this catalog of the works contained in “La Comédie humaine “, which was published a few days after Balzac’s death in the newspaper L’Assemblée nationale on August 25, 1850. Balzac considered these Scènes de la vie de campagne to be an almost-completed series, to which he intended to add only two works, Le Juge de paix and Les Environs de Paris. In the introduction to Etudes de mœurs au XIXe siècle that Balzac had written by his spokesman Félix Davin, Scènes de la vie de campagne is described in these terms: “After the dizzying tableaux (of Scenes from Military Life) will come the calm paintings of Country Life. In the scenes of which they will be composed, we’ll find men crumpled by the world, by revolutions, half-broken by the fatigue of war, disgusted by politics. There, then, rest after movement, landscapes after interiors, the gentle, uniform occupations of country life after the hustle and bustle of Paris, scars after wounds; but also the same interests, the same struggle, albeit weakened by the lack of contact, just as passions are softened in solitude. This last part of the work will be like the evening after a busy day, the evening of a hot day, the evening with its solemn hues, brown reflections, colored clouds, flashes of heat and muffled thunderclaps. Religious ideas, true philanthropy, virtue without emphasis, resignations are shown in all their power accompanied by their poems, like a prayer before the family’s bedtime. Everywhere, the white hairs of experienced old age mingle with the blond tufts of childhood. The broad contrasts between this magnificent part and the previous ones will only be understood when the Etudes de mœurs are completed.” This program applies fairly well to Le Médecin de campagne, Le Curé de village and even Le Lys dans la vallée. Balzac deviated significantly from this when he gradually discovered the life of peasants, and took stock, without illusions or sentimentality, of the greed and brutal passions to be found in the countryside: a spectacle far removed from the “prayer before the family goes to bed” that an idyllic vision of peasant life had initially led him to ignore. Les Paysans, which Balzac placed at the head of Scènes de la vie de campagne, is one of those ambitious novels. In the last years of his life. There are other examples of these immense projects that Balzac didn’t have time to complete: Les Petits Bourgeois, in Scènes de la vie parisienne, and Le Député d’Arcis in Scènes de la vie politique. Both works are abruptly interrupted in the middle of a chapter. Les Paysans, on the other hand, seems to have been carried through to the denouement: but to do this, it was necessary to use a sketch that was only a first draft that Balzac had not had time to complete. This abbreviated ending is just one of the enigmas of this novel, in which we encounter other obscurities, not all of which have been clarified. Not for lack of commentators. A first comprehensive study, too little quoted today, was devoted to the Farmersmore than eighty years ago, by the most famous Balzacian, the Viscount de Lovenjoul, in his book Les Paysans, the genesis of a novel by Balzac. Since then, careful studies have been published by seasoned specialists Marc Blanchard, Hervé Donnard, Pierre Macherey, Pierre Barberis, Madeleine Ambrière-Fargeaud and, recently, Thierry Bodin: all based on new, in-depth research, the latest on files from the Archives nationales. Despite these important and judicious contributions, many question marks remain. The first concerns the story of the novel itself. Les Paysans is, in fact, the realization of a long-standing project of Balzac’s, which has taken several contradictory forms. The subject is the struggle of peasants against the large landowners who hold the land they covet: this situation is not peculiar to France, and can be found in many countries and at different times. latifundia. Balzac had foreseen this subject as early as 1833, when he published The Country Doctor. Indeed, in his album Pensées, sujets, fragments, we find a “program for 1834” containing the title that would long be that of Les Paysans, that of a proverb that aptly describes this situation: Qui terre a guerre a. In this program, the subject is defined as follows: “The struggle between the peasants of the district and a large landowner whose woods they devastate – the guard is killed, no culprits – a beggar like Coupeaux, old women looking scoundrel, jealous, etc. good character of the guard, his wife, the lord.” This is exactly the subject of Peasants. It’s clear from the name Coupeaux, one of the accused, that Balzac was thinking of the murder of Paul-Louis Courier in 1825, which was accompanied by a trial that was followed with curiosity. However, it was not this clearly defined project that Balzac first realized, but a related one that has long been confused with it. In 1835, Balzac began a novel – or short story – entitled Le Grand Propriétaire, the manuscript of which has been preserved. Mme Madeleine Ambrière-Fargeaud showed that the idea had come to Balzac after reading a novel by the Marquis de Custine, Le Monde comme il est, about which he had written an article. Balzac’s manuscript contains only an exposition, which was not continued, so we don’t know what the story was supposed to be about. Thierry Bodin found on the manuscript of Le Lys dans la vallée a series of titles written by Balzac in which Le Grand Propriétaire and Qui a terre a guerre are found one after the other, suggesting that these were two different projects. The Grand Propriétaire manuscript sets up the rivalry between a great lord, owner of a quasi-royal castle, and the neighboring town’s burghers, whose coalition threatens him. No indication of the outcome. There are no peasants in this sketch, the action takes place in Touraine, between Loches and Châteauroux, and the bourgeois coalition is a spider’s web of family alliances, with the very names Balzac would later use in Ursule Mirouët to describe the conspiracy of the Minoret heirs. It’s a novel that portrays the rivalry between the bourgeois class and the former nobles who have resettled on their lands, a work in which Balzac declared, in a letter to Alfred Nettement, that he wanted to paint “a beautiful character of a great lord”. All this is a long way from the subject of Les Paysans. It was in 1838 and 1839 that the subject of Les Paysans took on its definitive form. In September 1838, Balzac wrote to Madame Hanska that he had just begun Le Curé de village and that he had just “written two in-8° volumes entitled Qui a terre a guerre “. This mention is confirmed by a letter to Théophile Gautier in April 1839, which announces that the novel with this title is “in manuscript and finished”, and describes it in the following terms: ” Qui a terre a guerre is the painting of the struggle, deep in the countryside, between the big landowners and the proletarians, and the influence of demoralization through the abandonment of Catholic doctrines. “. That’s what Les Paysans is all about. The entire first part of the novel would therefore have been written, at least in first draft, at this date. All that remains is to find a publisher and write the second part, which is, in truth, the essential part. The rest is just anecdote – and disappointment. For opposing reasons, the subject matter displeased both the newspapers that supported bourgeois monarchy and the Legitimists, who preferred the “handsome character of the great lord” to the clumsy, combative cuirassier depicted in the novel. La Presse and Les Débats rejected Les Paysans for their serial. Years go by without a decision. Finally, in 1844, Balzac admirer Alexandre Dujarier became manager of La Presse. A contract is signed. Balzac announced this to Madame Hanska in 1844: “The gauntlet has been thrown down. This work, eight years in the making, is about to be published… I’m trembling with what I have to do in 28 days. Les Petits Bourgeois and Les Paysans are six volumes each. “It was apparently on this date that Balzac went back to his first draft and drew up the final version of the first part. Les Paysans appeared in 16 serial editions in La Presse between December 3 and 21, 1844. It was a catastrophe. Balzac, congratulated by his friends, believed in triumph. “People shouted ‘Molière’ and ‘Montesquieu! On m’a salué Roi!” he wrote on January1, 1845. Readers of La Presse reacted quite differently. The figure of seven hundred unsubscribers in just a few days is quoted. In any case, the newspaper’s management was in a hurry to finish before the end-of-year renewals: they hastily began Alexandre Dumas’ La Reine Margot. Dujarier refused to give up. But he was killed in a duel a few weeks later, on March 11, 1845. Girardin, the newspaper’s owner, regretted the advances he had made to Balzac: he wrote him a nasty letter, and Balzac, furious, undertook to repay it. No more was heard of Les Paysans, the manuscript of which Balzac took to the Ukraine in September 1847. After her husband’s death, Eve de Balzac tried to finish Les Paysans herself. She soon gave up, and confined herself to editing the chapters Balzac had sketched out in first draft, which will be described later. Les Paysans was published under these conditions from April to June 1855 in the Revue de Paris. This chronology of the writing process clearly shows the difficulties Balzac encountered, first in defining his subject, then in developing it. Why so much procrastination, why so much perplexity? And why, in the end, such a strange thesis in favor of latifundia against smallholdings, which were to give France its rural physiognomy at the end of the century and ensure a long period of agricultural prosperity until 1914? Is it possible to find a link between these different questions and to link them to a hypothesis that provides an answer? It’s the dates that give us the explanation for these reversals and the elements of this answer. The three key dates in the gestation of Les Paysans are the end of 1833, indicating the program for 1834; 1835, when Le Grand Propriétaire was written; and 1838-1840, when Les Paysans was written in first draft. However, two of these dates are also key dates in Balzac’s affair with Madame Hanska, and the third is that of a sibylline statement by Balzac, too often overlooked, that relates to the same concern. The end of 1833 saw the first meetings in Neuchâtel and Geneva. Balzac notes on his program this strange subject, so far removed from his usual preoccupations and descriptive domain, but so close to the natural preoccupations of a great Polish lady whose fortune is invested in one of these immense estates. The year 1835 was the year of the meeting in Vienna. Balzac wrote the beginning of Le Grand Propriétaire, which shows “a handsome grand seigneur character” up against the covetousness of the department’s bourgeoisie. We explain to him that he hasn’t understood a thing: these are not bourgeois but peasants, violent, devious brutes. Balzac abandons Le Grand Propriétaire, returning to his original concept. In July 1840, the subject of Les Paysans was rejected by all the newspapers to which Balzac proposed it. So he wrote this strange sentence to Madame Hanska: ” Les Paysans will be for M. de Hanski if I make them. I’ve reached the end of my resignation. “What does M. de Hanski have to do with this story if he doesn’t give us the answer to the riddle by making us understand that Les Paysans is a promise from Balzac to Madame Hanska? The sentimental significance of Les Paysans then appears in the background, leading Balzac to a historical misinterpretation. The disappearance of the latifundia, which led to the emergence of smallholdings throughout Europe, also meant the disappearance of the great landed fortunes of Count Hanski and the entire military aristocracy endowed by kings. Is the Count having trouble with his muzhiks? We don’t know, but shortly after her death, villages belonging to Madame Hanska burned to the ground. Fatality or malice? With more zeal than success, Balzacians have sought to model General de Montcornet, the master of the great estate who defends himself so courageously against the elusive Lilliputians who ravage his lands. But how can we fail to think of Count Hanski, marshal of the nobility, similar in stature, authority, “tonnage” if you like – and also similar in courtesy, in confidence, to the general portrayed in The Peasants ? Of course, writer Emile Blondet, a guest at the château, is Balzac to Madame Hanska. But are the Burgundian peasants in the novel – rebellious, drunken, lazy, pests – a faithful reflection of the peasants of Normandy, Franche-Comté or Touraine? Doesn’t Balzac a little hastily and arbitrarily equate them with a semi-wild, almost animal-like social class that might have been found in the Ukraine, but which it’s hard to accept as the prototype of the French peasant? Among the research carried out on Les Paysans, some of the most significant are the surveys carried out by Thierry Bodin in the files of the Archives nationales. However, the figures he cites, which contain valuable information, reveal a picture of the peasantry that is markedly different from the one given by Balzac. The most common offence is poaching. The figures for fines vary according to department and season, but they’re not terrifying. Three offenses in one month in 1830 and 1832 in Seine-et-Oise, 18 in a favorable period in 1836, in Indre 18 official reports in 1832, 24 in 1835. Few rapes. Very few fires, except in 1833 in Nièvre and in 1834 in Seine-et-Oise. And yet, as we sadly know, this is one of the systematic processes of hatred. It would appear from this file, and from the information gathered by Hervé Donnard, that the main demands of the poor peasants were a certain tolerance of poaching, and the maintenance of their acquired rights to glean and hoard, with minor destructions. Balzac himself confirms this impression with the example of neighboring estates belonging to the Soulanges and Ronquerolles families, who live in peace because they turn a blind eye to these petty thefts. It was General de Montcornet’s rigor that caused the drama. Private vindictiveness fuels it. Ultimately, the lesson of the drama is that the conspiracy of the bourgeoisie is more formidable than the “grumbling” of the peasants. These reflections that come to mind when reading Les Paysans cause a kind of embarrassment. Balzac’s thesis in his novel is not likely to dispel it. He came to regard the subdivision of properties in the Argenteuil area as a catastrophe. Was it necessary, in order to protect the seigneurial parks, to abandon the suburban food crops that supplied Paris throughout the late 19th century? By the end of the novel, the Aigues estate has been sold and divided up, and the forest has been replaced by an agricultural valley. It may be a downfall, but it’s certainly a drama, as transitional periods often produce, and Balzac is no doubt right to see it as one of the dramas of his time, to make us understand it, to associate his reader with it: but we can draw no other lesson from it than the one we draw from all the destructions of what belongs to the past by what belongs to the future. Balzac’s difficulties in the second part of Les Paysans are of a different nature. First of all, it’s important to realize that the current division into two parts is somewhat artificial. In fact, Balzac had written and edited all the chapters grouped together in Part One, plus the first four chapters of Part Two. All in all, it was a huge exhibition, but the battle had not yet begun. The six chapters we read next are merely a first draft that Balzac had printed cheaply by a printer to have the equivalent of what, for us, is a typewritten copy of his manuscript. Clearly, these chapters would have been considerably expanded and transformed in the final version. Eve de Balzac rightly decided not to develop them. She even preferred this flawed first draft to a more elaborate text because she saw it, she said, as an instructive document on her husband’s working method. She wasn’t wrong. It’s a strange, disparate collection, but at the same time it’s the pieces of a puzzle that we first encounter among Balzac’s papers. In other examples of amplification in Balzac’s manuscripts, we find a rapid first draft, extraordinarily enlarged and enriched by multiple additions ranging in scope from half a sheet to a notebook of ten or fifteen pages. But in such cases, the first draft always indicates the essentials, establishes the characters and describes the action: it’s a sketch that Balzac enriches. In the single example provided for the final chapters of Les Paysans, the new characters who are about to enter the scene – the bourgeois of Blangy and La Ville-aux-Fayes – are listed and described, but the action is not sketched out at all. In short, Balzac has prepared pieces that are destined to take their place in a whole, and which are more or less “finished” portions of that whole: but the chain on which they are to be staggered does not exist. Balzac did, however, indicate something of this, but in a chapter that appears to be a kind of aide-memoire designed to remind the novelist of the means he intended to use to set up his plot. This chapter is so alien to the story, so obviously a kind of notepad, that Mme de Balzac decided not to include it in the final version. This is a conversation in which one of the characters, a young Parisian who is indifferent to the partners’ murky schemes but knows them very well, lists the counter-maneuvers by which General de Montcornet could respond to the coalition formed against him and thus break it, or at least put up effective resistance. Clearly, Balzac is enumerating the adventures he intended to feed his novel into the six in-8° volumes he had planned. So, in what Balzac had prepared, we have both puzzle pieces and “instructions for use”. It’s the first time we’ve come across this work device in Balzac. In part, it consists in adding a second exposition to the previous one, thereby multiplying the characters to such an extent that the reader finds it difficult to identify them, while the author is left with a huge ensemble of choristers he no longer knows how to direct. This plethora, which contrasted with the schematic indications given by the author, is perhaps one of the reasons why the Peasants were abandoned: and perhaps that of the Député d’Arcis and the Petits Bourgeois. Where did Balzac, apparently a stranger to peasant life, come across the vivid, vigorous characters that give his novel the power and richness that make it one of his greatest works? He set the action of Les Paysans in Burgundy, and Balzac is not known to have spent any time in Burgundy. This Sologne, this Corrèze that he transports to the borders of Morvan and Yonne, when did he cross them? Le cabaret du Grand I vertThe Tonsard family of poachers and pirates, Father Fourchon and his accomplice Little Mouche, the voluptuous usurer Rigou, his fine meals and his pretty maids, his drunkards, his country wardens, his old women, a wild and devious people, give an extraordinary impression of reality and strangeness at the same time, like following a traveler in an unknown country. Memories of Touraine, boldly transposed, of Berry peasants glimpsed during Balzac’s stays at Frapesle, near Issoudun, with his friends Carraud, of walks around La Bouleaunière, near Nemours, where he would join Mme de Berny? The most likely location is simpler and closer. The bush where Balzac had met these wild tribes was just outside Paris, in the Isle-Adam valley, today so lush, but at the time so remote and wooded, where Balzac had spent long periods of time during his youth. If the small imaginary town around which the action of Farmers is named in the novel La Ville-aux-FayesIt’s a tribute to M. de Villers-La Faye, an old friend with whom the eighteen-year-old Balzac would forget the boredom of his family home in Villeparisis. The Marquis de Villers-La Faye owned a beautiful property there, which he too had to defend against covetousness. He had once owned a château and a beautiful estate in the Yonne region, which he was forced to abandon after a series of difficulties, trials and misfortunes, the story of which may have provided Balzac with some of his documentation. He was said to be fussy, litigious and litigious. His Isle-Adam estate, which extended into the immense Cassan park, seems to have given Balzac the configuration he imagined for the immense Aigues park, the setting for the drama recounted in Les Paysans. This layout had already inspired Balzac to describe the estate in Le Grand Propriétaire, which he situated between Loches and Châteauroux. All he had to do was take it up and amplify it in the description of Les Aigues that appears at the start of the novel in a letter sent by Emile Blondet to one of his friends. Balzac’s walks around Isle-Adam and the memories of the Marquis de Villers-La Faye may have provided a good deal of the original features that he transposed into his novel. However, another part of Balzac’s documentation has a very different origin. It was the circumstances surrounding the murder of the famous pamphleteer Paul-Louis Courier, in 1825, that gave Balzac an idea of the violence of the hatred provoked by the fury of the peasants when a landowner opposed the poaching and raiding they took for granted. Here again, this origin is certain, and even signed by the mention of Coupeaux’s name in Balzac’s album notes above. It’s a landmark. But that’s all it is. None of the facts that Balzac may have known, and that we can find in the accounts of the investigation and trial that followed the murder, are to be found in Les Paysans. It’s only a certain atmosphere of hatred and complicity that is common to Balzac’s novel and the attack, which was covered up by the silence of all those questioned. Balzac’s systematic distortion of reality in describing the peasants he portrays can perhaps be explained by literary transposition. The novels of Fenimore Cooper had been, along with those of Walter Scott, some of the works Balzac had read with predilection during his youth. He had especially admired the author of The Last of the Mohicans ‘ depiction of an unknown human species, all animal, instinctive, a race both distrustful and daring. At the same time, he had learned from these books that the landscape is not a spectacle, but a theater of operations, a savannah populated by traps in which everything is a sign and a warning, the creaks, the scree, the tracks. This mysterious, treacherous countryside, which he had transposed in Les Chouans, he found again in Les Paysans. And the peasant population he transposes in the same way, into poachers, trackers, nocturnal vagabonds, outlaws as dangerous and determined as the Breton marquis’s peasants. He describes Mohicans, Burgundy Sioux and Apaches. Les Aigues is a New World forest, with the enemy attacking, sneaking in and regrouping, as alien to the rest of mankind as the Redskins were to the whites. This study of the customs of an unknown tribe joined other literary explorations of the same kind. In the heart of Paris, Eugène Sue had discovered the same wild population living in their burrows, prowlers of the night in selvedge slippers, supple, invisible, pilferers, killing when necessary, elusive. Success had shown that these “Mohicans of Paris” provided excellent soap opera material. Balzac, presumably, wasn’t too keen on showing that the confines of Burgundy were as unexplored a territory as the suburbs of Paris. This was part of his nomenclature of the social caves we pass by without seeing them, a voyage of discovery to which we can relate Le Père Goriot as well asHistoire des Treize. This dramatization of the French campaign has its advantages and disadvantages. It is historically debatable, but it provides strong figures, characters who remain in the reader’s memory. It’s this menagerie that makes Les Paysans so interesting and valuable today. This is one of Balzac’s great novels, in its scope, variety and resonance. But you can also sense the writer’s fatigue: he mixes two series of characters with different passions and interests, without succeeding in making a whole; he multiplies the number of extras, as if seized by a kind of vertigo of nomenclature, and the reader ends up no longer identifying them. He makes the Aigues estate into a sort of immense plateau to contain all this figuration, and he gives it such vast proportions that we can’t get an exact idea of where the drama is taking place, and wish for a map to embrace this topography. This propensity for proliferation and gigantism, still only slightly apparent in Le Député d’Arcis, but already much more pronounced in Les Petits Bourgeois, is perhaps the reason why Balzac abandoned his major projects, which are too easily attributed to his declining health. It is probably related to another aspect of Balzac’s later works: his attraction to pure nomenclature, already evident in Les Employés and so evident in Les Comédiens sans le savoir. It seems that Balzac is in a hurry to complete this gallery of originals and sometimes simple passers-by, which enables him to show the transformations of social life and the perils that appear. The drama that seemed to him to be the essence of the novel at the start of his career is now no more than a piece of machinery that supports the movement of figures characteristic of contemporary society, and whose role is increasingly to show the chain of cause and effect.

Mother Tonsard

The Story The story takes place under Louis-Philippe, in 1823, at the Château des Aigues in Burgundy. Writer and journalist Emile Blondet is welcomed by his friends, General Comte de Montcornet and his wife Comtesse de Montcornet. Following the successive revolutions of 1789 to 1799 and the fall of the monarchy, most seigneurial and church property was confiscated by successive republics and sold to the emerging bourgeoisie. This is what happened to the large Aigues estate bought in 1790 by a former singer, Mademoiselle Laguerre, who had been forgotten by the guillotine and the aristocracy, and wanted to get away from Paris. This precious lady concentrated all her energy and finances on decorating the apartments and adorning the Aigues park, which she adorned with the most beautiful flowers and fruit, while neglecting the forestry and agricultural heritage of the vast Aigues land, which was over-exploited by peasants for timber and poaching. On Mlle Laguerre’s death, the Aigues were bought by General Montcornet, who gradually became aware of the thefts and plundering carried out on his lands with the complicity of Gaubertin, Mlle Laguerre’s former steward, and dismissed this swindler, replacing him with Sybillet. During this restructuring, Vaudoyer, the estate’s field warden, until then protected by Gaubertin, was also dismissed by the general for his complacency towards the peasants who raided the estate’s lands, as was Courtecuisse, the estate’s janitor. Both were replaced by ex-military men the general liked: Groison, a former non-commissioned officer in the ex-imperial guard, became the new forest ranger, and Michaud, a former maréchal des logis and chief in the cuirassiers de la garde, became chief ranger of Les Aigues. To oversee the estate, Michaud enlisted the help of three capable ex-servicemen, known and chosen by the general.

Michaud and his wife

These dismissals and the reinforcements put in place will be the downfall of the large owner. Indeed, the general doesn’t know that in the countryside, the rural population is welded together by genealogical ties (affiliations, alliances and kinships) which mean that families are linked to each other, closely or remotely, by a relative. These kinships form an ironclad solidarity between the peasants and petty bourgeois against the great landowner of Aigues. In the provinces and especially in the countryside, everyone has a son, brother, cousin, nephew, son-in-law…notary, mayor, justice of the peace, gendarme, sub-prefect ready to intervene on their behalf. This enemy will be all the more powerful and dangerous in that Gaubertin and Courtecuisse have, over the years and especially while in the service of Mlle Laguerre, forged strong ties with the peasants and villagers of the neighboring communes, to whom they have extended the benefits of the aforementioned liberalities, and who now hold them in high esteem and support. In recognition, Gaubertin became mayor of the commune, and after his dismissal, Vaudoyer was appointed by Gaubertin to guard the Ronquerolles timber buyer. This coalition, led by the mayors of Couches, Blangy (Rigou) and La-Ville-aux-Fayes (Gaubertin), includes all public and private services and has a monopoly over the whole country. The aim here is to prevent the Count from reviewing the laws governing his property, and to make him understand that he is an intruder and an unwanted foreigner. A plot was hatched against him as soon as he became a threat to the peasantry. Drama ensues with the murder of head warden Michaud at a time when General Montcornet believes he has restored order and discipline to his estate. As the communes were all in cahoots, no culprit and no proof could be found, despite the considerable resources deployed by the general. For the general, there’s no doubt that Michaud’s assassination was a warning to force him to leave the country. The proof comes in the form of a conversation with the peasant Bonnébault, who holds him at gunpoint. The latter confides in him that if he isn’t killed by him, it will be by someone else, for he has only enemies around him, and enemies far more powerful than he imagines. It was at this point that the Comte abdicated and decided to sell his estate, which was sold in lots to the all-powerful Rigou. The bourgeoisie and the peasantry have won. 1845

The characters Emile Blondet: Born in 1800, Emile was a journalist and prefect as a result of his mother’s affair with the prefect of Alençon. He marries General Montcornet’s widow, Virginie de Troisville. Sophie Laguerre: (1740-1815) Maintained actress and owner of Les Aigues before General Montcornet. Sibilet père: Clerk at the Ville-aux-Fayes court. Married Miss Gaubertin-Vallat. This union gave birth to Adolphe in 1791, who was employed at the Land Registry and later became a steward. Adolphe Sibilet: Husband of Adeline Sarcus, with whom he has two children. Rigou: A former Benedictine monk, Grégoire Rigoud is mayor of the commune of Blangy. François Gaubertin: Born in 1770, intendant at Les Aigues, then mayor of La Ville-aux-Fayes. He marries Isaure Mouchon. Claude Gaubertin: Son of François and Isaure Gaubertin. Claude is a solicitor in Ville-aux-Fayes. La Godain: Blangy peasant with a son who married Catherine Fourchon. Courtecuisse: General guard at Les Aigues. Fourchon : Born 1753 – Blangy handyman. Father of two daughters, Philippine, who married François Tonsard, a cabaret owner, with whom she had four children: Jean-Louis, Nicolas, Catherine and Marie. His second daughter has a natural son, little Mouche. Justin Michaud: This former military man becomes general warden at Les Aigues. He was assassinated in 1823. Montcornet: (1774-1838), the Count of Montcornet was made General and then Marshal of France. He married Virginie de Troisville (1797), who after the Count’s death became the wife of Emile Blondet. Catherine Tonsard: Daughter of François Tonsard and Philippine Fourchon, wife of Godain. Mère Tonsard: Peasant woman in Blangy, mother of François cabaretier. La Bonnébault: Old farmer in Blangy. She has a grandson Jacques who served as a soldier in the army.

1) Source analysis: Preface from the 20th volume of La Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs in 1987, based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris.

2) Source history and arguments Wikipedia.

3) Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde”, Gallimard.

No Comments