The Chouans

LA COMEDIE HUMAINE – Honoré de Balzac XIIIe volume des œuvres complètes de H. DE BALZAC by Veuve André HOUSSIAUX, éditeur, Hébert et Cie, Successeurs, 7, rue Perronet, 7 – Paris (1877)

Scenes from military life

Marie de Verneuil

THE CHOUANS Scenes from military life

Etude de mœurs published in Paris in 1829 by Urbain Canel

Analysis of the work This novel belongs to the last of the great series of 19th-century studies of manners, the Scènes de la vie militaire (Scenes from Military Life). Here’s how Balzac had Félix Davin describe this ensemble in hisIntroduction aux Etudes de mœurs au XIXe siècle , published in 1825: ” Scenes from Military Life is a consequence of Scenes from Political Life. Nations have interests, these interests are formulated in a few privileged men destined to lead the masses, and these men who stipulate for them set them in motion. Scènes de la vie militaire (Scenes from military life ) is therefore intended to depict the main features of life as the masses march to battle. It will no longer be interior views taken in towns, but the painting of an entire country; it will no longer be the mores of an individual, but those of an army; it will no longer be an apartment, but a battlefield ; no longer the narrow struggle of a man with a man, a man with a woman or two women with each other, but the clash of France and Europe, or the Bourbon throne that a few generous men want to raise in the Vendée, or emigration grappling with the Republic in Brittany, two convictions that allow anything. Balzac had big plans for this series. He also planned Les Traînards, the story of the Grande Armée during the retreat from Russia, and sketched out Mademoiselle du Vissard, another episode from the Wars of Brittany and the Vendée. In reality, Les Chouans was not originally a novel destined for such a prestigious position. Le Dernier Chouan ou la Bretagne en 1799, published in 1829 (the title of the book at the time), was in fact the last of Balzac’s early novels, and was by no means part of the plan for La Comédie Humaine, which Balzac was to conceive only several years later. When he wrote it, Balzac was then an unknown writer, or, more accurately, a writer sadly known by mediocre novels published under various pseudonyms and by bookshop jobs published without a signature. This Last Chouan was his last cartridge, his last attempt, this time under his own name, to be taken into consideration. And this latest attempt, it has to be said, ended in failure, less humiliating than the previous ones, but not very encouraging for the future.  The novel’s gestation had been rapid, but its publication was painful. The liquidation of Balzac’s last two businesses, his printing works and type foundry, took place between April and August 1828. By the spring, Balzac, ruined and saved from bankruptcy by his family and a few friends, had to find other resources, and he turned to his writing business, the only means left to him. After taking on a few anonymous jobs, he got back to work on a project he’d been working on for several years: writing historical novels in the style of the hugely successful English writer Walter Scott. In a preface to Le Dernier Chouan, which was not found in his papers until much later, Balzac explained his project. The idea was to produce a series of novels entitled “Histoire de France pittoresque”, devoted above all to the civil wars that had divided the French. A historical fact of which he had become aware “by the purest chance”, he says, and which belongs to the annals of the Chouannerie, provided him with the material for his novel. It was the capture and death of one of the leaders of the insurrection by means of a spy sent to seduce him. The case took place in 1798. The story was easy to tell. “It requires no research,” Balzac specified, “except that of its localities.” Balzac had originally intended to exploit this situation by turning it into a play. It was faster and much more cost-effective. The canvas for this piece has been found. In Balzac’s papers, it bore the unfortunate but significant title Tableau d’une vie privée. It’s the outline of his novel, abandoned almost immediately. As early as September 1828, Balzac, eager to learn more about “the localities”, as he called them, asked General Baron de Pommereul, who had been a great friend of his father’s in Tours, to receive him for a few weeks in the château he owned in Fougères, the town he chose as the center of his novelistic action. He arrived in a sorry state, thin, hungry and strangely dressed. They fed him, comforted him and introduced him to the Bretons who had chouanné and conscientiously massacred him. As he wrote, he had before his eyes the valley that was the scene of the drama. He was told stories about the Chouans. He quickly wrote a first draft. On his return to Paris, the process of fine-tuning was more difficult and slower, and the search for a publisher more difficult. Balzac was greatly helped in both these tasks by a recent friend, the Berrichon Hyacinthe Thabaut de Latouche, fifteen years his senior and known for having discovered the influential critic André Chénier. Around this time, Latouche had begun a novel entitled Fragoletta or Naples in 1798, which described a situation quite similar to the one Balzac had chosen for Le Dernier des Chouans or Brittany in 1799. The two friends worked together, sharing their manuscripts and, more dangerously, their comments. Their friendship outlived the collaboration. Latouche, paternal and attentive, helped Balzac wallpaper his new apartment in the rue Cassini. He went even further. He contributed to the publication of Le Dernier Chouan, offering to pay half of the production costs to the publisher Urbain Canel. Latouche believed in Balzac’s talent, and Balzac believed in it too: as a result, he multiplied the number of corrections, which significantly increased the costs to which Latouche contributed. The novel was finally published in February 1829. Despite the best efforts of the two friends, the welcome was cold. There were only four articles, one by Latouche in Le Figaro, the other by a former collaborator of Balzac’s, and two others that were a riot. By the middle of the year, we had sold just 300 copies, and by the end of the year 500. It was a disaster for Latouche. Balzac was more indifferent to this setback. He had just published Physiology of Marriage, which caused a scandal and made him an overnight celebrity.

The novel’s gestation had been rapid, but its publication was painful. The liquidation of Balzac’s last two businesses, his printing works and type foundry, took place between April and August 1828. By the spring, Balzac, ruined and saved from bankruptcy by his family and a few friends, had to find other resources, and he turned to his writing business, the only means left to him. After taking on a few anonymous jobs, he got back to work on a project he’d been working on for several years: writing historical novels in the style of the hugely successful English writer Walter Scott. In a preface to Le Dernier Chouan, which was not found in his papers until much later, Balzac explained his project. The idea was to produce a series of novels entitled “Histoire de France pittoresque”, devoted above all to the civil wars that had divided the French. A historical fact of which he had become aware “by the purest chance”, he says, and which belongs to the annals of the Chouannerie, provided him with the material for his novel. It was the capture and death of one of the leaders of the insurrection by means of a spy sent to seduce him. The case took place in 1798. The story was easy to tell. “It requires no research,” Balzac specified, “except that of its localities.” Balzac had originally intended to exploit this situation by turning it into a play. It was faster and much more cost-effective. The canvas for this piece has been found. In Balzac’s papers, it bore the unfortunate but significant title Tableau d’une vie privée. It’s the outline of his novel, abandoned almost immediately. As early as September 1828, Balzac, eager to learn more about “the localities”, as he called them, asked General Baron de Pommereul, who had been a great friend of his father’s in Tours, to receive him for a few weeks in the château he owned in Fougères, the town he chose as the center of his novelistic action. He arrived in a sorry state, thin, hungry and strangely dressed. They fed him, comforted him and introduced him to the Bretons who had chouanné and conscientiously massacred him. As he wrote, he had before his eyes the valley that was the scene of the drama. He was told stories about the Chouans. He quickly wrote a first draft. On his return to Paris, the process of fine-tuning was more difficult and slower, and the search for a publisher more difficult. Balzac was greatly helped in both these tasks by a recent friend, the Berrichon Hyacinthe Thabaut de Latouche, fifteen years his senior and known for having discovered the influential critic André Chénier. Around this time, Latouche had begun a novel entitled Fragoletta or Naples in 1798, which described a situation quite similar to the one Balzac had chosen for Le Dernier des Chouans or Brittany in 1799. The two friends worked together, sharing their manuscripts and, more dangerously, their comments. Their friendship outlived the collaboration. Latouche, paternal and attentive, helped Balzac wallpaper his new apartment in the rue Cassini. He went even further. He contributed to the publication of Le Dernier Chouan, offering to pay half of the production costs to the publisher Urbain Canel. Latouche believed in Balzac’s talent, and Balzac believed in it too: as a result, he multiplied the number of corrections, which significantly increased the costs to which Latouche contributed. The novel was finally published in February 1829. Despite the best efforts of the two friends, the welcome was cold. There were only four articles, one by Latouche in Le Figaro, the other by a former collaborator of Balzac’s, and two others that were a riot. By the middle of the year, we had sold just 300 copies, and by the end of the year 500. It was a disaster for Latouche. Balzac was more indifferent to this setback. He had just published Physiology of Marriage, which caused a scandal and made him an overnight celebrity.  Le Dernier Chouan was considerably revised in a second edition published in 1834. This is the edition we are reproducing.

Le Dernier Chouan was considerably revised in a second edition published in 1834. This is the edition we are reproducing.

The story In 1799, during the French Revolution, Breton peasants armed themselves for the return of the king and against Commander Hulot’s Republican troops. An aristocrat, Marie de Verneuil, is sent by Joseph Fouché to seduce and capture their leader, the Marquis de Montauran, known as Le Gars. She must be helped by a clever, ambitious and unscrupulous policeman, Corentin. However, she falls in love with her target. Against Corentin and the Chouans who hate her, she will do everything in her power to marry the Marquis. Deceived by Corentin into believing that the Marquis loves his mortal rival, Madame du Gua, she orders Commandant Hulot to destroy the rebels. Discovering the deception too late, she sacrifices herself in an unsuccessful attempt to save her husband the day after his wedding.

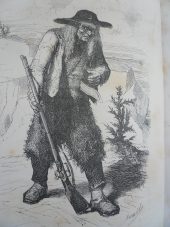

Corentin

Walk on land

Mme de Verneuil and Mme du Gua

The characters Marie de Verneuil: (1773-1799) Natural daughter of Victor-Amédée, Duc de Verneuil and Blanche de Castéran. She married Danton, then the Marquis de Montauran. Marquis de Montauran: Alphonse de Montauran marries Marie de Verneuil, widow of Danton. He was killed in 1799. Commandant Hulot: Count Hulot de Forzheim, Marshal of France, born in 1776. Joseph Fouché: (1759-1820) was a revolutionary politician charged with capturing the Marquis de Montauran. Corentin: (1777) Policeman in the pay of Joseph Fouché and Marie de Verneuil’s partner in the plot to arrest Montauran. Madame du Gua: Alleged rival of Marie de Verneuil. In fact, the du Gua-Saint-Cyr family is represented by a young boy and his mother who were killed by the Chouans in 1799. In the words of Félicien Marceau, author of ” Balzac et son monde – Gallimard “, and I quote: “the name du Gua was usurped around the same time by the Marquis de Montauran and by a woman who accompanied him, perhaps the Countess du Gua”.

1) Source analysis: Preface from the 19th volume of La Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs in 1987, based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris.

2) Source story: Wikipedia, the universal encyclopedia.

3) Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

No Comments