The Deputy of Arcis

THE HUMAN COMEDY – Honoré de Balzac XIIth (twelfth) volume of works of Honoré de Balzac edited by widow André Houssiaux, publisher, Hebert and Co, successors, 7 rue Perronet – Paris (1874)

Scenes from political life

THE DEPUTY OF ARCIS

Study of manners published in Paris in 1854 by Potter, Michel Lévy

Analysis This volume contains the last two of the works Balzac had placed in the Scènes de la vie politique, Le Député d’Arcis, an unfinished novel, and a short story Z. Marcas, who together with A murky affair and Un épisode sous la Terreur, all that Balzac had written about this important division of The Human Comedy. About Le Député d’Arcis In 1835, when he set out the main lines of his work, Balzac defined Scènes de la vie politique as a series showing the dramas produced by “the appalling movement of the social machine and the contrasts produced by particular interests intermingling with the general interest”. This definition, which Balzac dictated to his friend Félix Davin for his Introduction aux études de mœurs au XIXe siècle, hardly applies to what we read in Le Député d’Arcis, histoire d’une élection en province. Set during the July 1830 monarchy, Le Député d’Arcis describes the new conditions for arrivisme, the new careers and the new beneficiaries offered by the new regime. It’s a far cry from the Scènes de la vie politique that Balzac had defined in 1835. This novel, for which Balzac had begun work in 1842, was only partly written when Balzac began serial publication in the newspaper L’Union monarchique in April 1847. Only half of the novel had been written, the half about the preparations for an election in Arcis-sur-Aube. Balzac never wrote the sequel. It was only in 1935 that Marcel Bouteron published, under the title Le Député d’Arcis, the part of the novel authored by Balzac to the exclusion of this cumbersome sequel. Successive editors of La Comédie Humaine have followed this course, and we have followed it in the 1987 France Loisirs edition , based on the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris. The subject of an election in the provinces, accompanied by the conquest of a rich heiress, which is what was written about the Député d’Arcis, was neither an original idea nor a very pathetic situation. It was Charles Rabou, commissioned by Mme de Balzac, who wrote the sequel, a set of 18 in-8° volumes under the titles Le Comte de Sallenauve and La Famille Beauvisage. The subject matter is thankless, descriptions are likely to be dull, oppositions lead to dialogues whose subject matter is arid, triumph or failure, even with the lure of a large dowry, does not arouse the reader’s sentimental interest or anxiety. The election meeting with which the story begins is not immune to these various drawbacks, despite Balzac’s efforts to liven it up. Maxime de Trailles, a disquieting character familiar to Balzac’s readers from a few Scènes de la vie parisienne (Scenes from Parisian Life), makes an enigmatic entrance that lifts the interest a little, without fixing it sufficiently. Despite this, the reader is not captivated by the characters, the circumstances or the interests involved. He can’t guess at a tomorrow he’s waiting for without curiosity. It’s another system of references that makes the Député d’Arcis so interesting and true. This novel is alive, and even truly intelligible, only to avid readers of Balzac. For, in reality, there is a sequel, the Twenty years after Une ténébreuse affaire : not twenty years later, but thirty-five years after the trial of the de Simeuse twins, which consecrated the triumph of Senator Malin de Gondreville and made him not only the owner of the large Simeuse estates, but the man who reigned over the Aube department. All the characters fromUne ténébreuse affaire are to be found in Le Député d’Arcis, just as they were in thirty-five years of history. In the center, the famous senator, who remained influential under the Restoration and all-powerful under the July monarchy, far away and barely visible. He is represented on site by his faithful Grévin, who is associated with his fortune: a sagacious octogenarian notary, old Grévin grafts his rosebushes, lives wisely, but it is he who secretly directs the election and above all it is he, Cécile Beauvisage’s grandfather and godfather, who will choose the heiress’s future husband. The others have made their mark, nibbling away at their cheese. The prosecution witnesses in the Simeuse trial have been protected, helped, are wealthy and occupy positions of power. The others, the Simeuse loyalists, gnaw their teeth in silence. All the secret feelings of the characters in Le Député d’Arcis are driven by this tragedy of yesteryear. But this original mark on them only commands secret feelings. Balzac’s profundity manifests itself in the fact that everything has settled down after thirty-five years, because history flattens out all social landscapes. History is like the plain of Waterloo: it’s an ossuary, but a secret ossuary, which has become a plain like any other on which wheat grows. So it’s not between the victors and the vanquished inUne ténébreuse affaire that the scores are settled, but between the victors who fight amongst themselves. New interests were born, and new threats emerged, producing unforeseen rivalries and unnatural alliances. When Maxime de Trailles arrives in Arcis, he’s carrying letters that accredit him to the officials who are creatures of Senator Malin de Gandreville, but he has the password that allows him to gain the trust of the former pickers and servants of the Simeuse household. Three days after his arrival, he dined at the almighty senator’s home, but the following day he spent the evening at the Château de Cinq-Cygne, where Duke Georges de Maufrigneuse, the son of the famous duchess, and a few other friends whom Rastignac and de Marsay had given him as mentors, were waiting for him. For the aristocracy of the Ancien Régime and those who had stripped it of its wealth also felt threatened by political newcomers, to whom Arcis’s election might give a seat as a deputy. A wonderful history lesson, so true, so eloquent, so eternal. One of Balzac’s best commentators, Alain, was fond of recalling the cruelty of the last image with which Les Chouans ends: Marche-à-Terre, one of the Vendée marquis’ most ferocious killers, leading his ox peacefully through the market in Fougères, an anonymous peasant. Le Député d’Arcis contains an equally bitter conclusion: everything passes, everything is forgotten, interest triumphs over all. But coalitions don’t silence hearts. Laurence de Cinq-Cygne, far away in her Parisian hotel, revered and immobile, is still present through her veto, the only word she can pronounce: Cécile Beauvisage, billionaire heiress but granddaughter of the notary Grévin, will never marry the young Marquis de Cinq-Cygne who was secretly destined for her. This refusal is the last echo of the drama of 1805. It is because of this bitter truth that Le Député d’Arcis is truly a Scène de la vie politique: for it contains a lesson in politics that goes beyond intrigue and anecdote, taking us to the heart of true history, not as it is told to us, but as it is. These insights, typical of Balzac, are one of the hallmarks of his depth and one of the aspects of his genius. But we don’t always understand them at first glance.

Source analysis: Preface (tome XIX) to La Comédie Humaine published by France Loisirs in 1987, from the full text published under the auspices of the Société des Amis d’Honoré de Balzac, 45, rue de l’Abbé-Grégoire – 75006 Paris.

The story The action takes place in the same setting as Une ténébreuse affaire, whose characters are reintroduced in the guise of their descendants: Giguet, Goulard, Michu, Violette, the Cinq-Cygne, Simeuse, Chargeboeuf, Malin de Gondreville (whose kidnapping gave rise to a trial and who is now eighty years old). Power struggles are just as fierce in this small provincial town, where two parties clash, each willing to do anything to secure their status as MPs. This book follows on from The Human ComedyThis is a very interesting story, since it includes Malin de Gondreville, now a senator, Eugène de Rastignac, himself a deputy elected for the second time, Maxime de Trailles, the Baron de Nucingen, the Marquise d’Espard, and a whole Parisian circle with a vested interest in settling the affair to their advantage. With the newly-elected candidate having to give up his seat to Maxime de Trailles, the novel was to end with the dandy’s triumph and his marriage to Cécile Beauvisage.

Source story :Wikipedia.

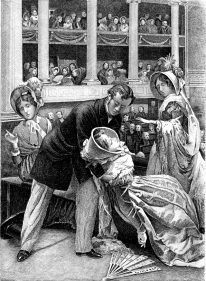

S. Giguet

Beauvisage

Genealogy ofcharacters BEAUVISAGE: Farmer in Gondreville. Has a son Philéas, born in 1792, a hosier who marries Séverine Grévin. Hence a daughter Cécile-Renée, actually the daughter of Melchior-René de Chargeboeuf. Cécile, who rumor has it thought was destined for the young Marquis de Cinq-Cygne, will probably end up as the wife of Maxime de Traille. GREVIN: Notary in Arcis, born in 1763. Married a Valet, resulting in a daughter Séverine born in 1795, who married Philéas Beauvisage. They give birth to little Cécile Beauvisage. MAXIME DE TRAILLE: Comte de Traille, born around 1792, Parisian dandy and politician. In this case, he ran for the seat of deputy, which he won at the expense of the newly elected member. GIGUET : Champagne family including a gendarmerie officer (see Une Ténébreuse Affaire and Député d’Arcis), a sister who married Marion, a brother made colonel who married a Hamburg woman who died in 1814, giving rise to 3 children: a son Simon Giguet, a lawyer, and two sons who died in 1818 and 1825. GOULARD: Mayor of Cinq-Cygne. His son Antonin is sub-prefect of Arcis. MICHU: Intendant of the Simeuse, guillotined in 1806. His son François, born in 1793, became a public prosecutor in Arcis. François marries a Girel. VIOLETTE: A champagne farmer, his grandson Jean is a hosier. SIMEUSE (de): “Ximeuse is a fiefdom in Lorraine. The name was pronounced Simeuse. This family included a Marquis de Simeuse who married a widowed Cinq-Cygne under Louis XIV. Two sons, one a vice-admiral, the second Jean, married Berthe de Cinq Cygne. They were both executed in 1792. This union produced twin brothers, Marie-Paul and Paul-Marie, born in 1773. Both killed in 1808(See Une Ténébreuse Affaire). CHARGEBŒUF: (Duinef de) Noble family and one of the most illustrious of the old county of Champagne represented by : The Marquis de Chargeboeuf born around 1737, A demoiselle de Chargeboeuf, whom Talleyrand sometimes visited, Melchior-René de Chargeboeuf, sub-prefect at Arcis and then Sancerre, probable father of Cécile Beauvisage. A Chargeboeuf, secretary to Attorney General Grandville. A Chargeboeuf who lives in Coulommiers with his wife and whose daughter is seduced and married by Vinet (See Pierrette). A widow living in Provins with her daughter Bathilde, who marries Rogron (Pierrette). The Cinq-Cygne family is a younger branch of the Chargeboeuf family. CINQ-CYGNE: (Duinef de) Noble family from Champagne, represented by : A Cinq-Cygne widow, who married a Simeuse under Louis XIV; Berthe de Cinq-Cygne married Jean de Simeuse, producing twin sons Marie-Paul and Paul-Marie; A Comte de Cinq-Cygne, Berthe’s brother, died before 1789, leaving a widow who died in 1793 and two children: Jules, killed in the Princes’ army, and Laurence, born in 1781, who married Adrien de Hauteserre, who took his name: Berthe, who married Georges de Maufrigneuse, and Paul, deputy of Arcis. MALIN DE GONDREVILLE: Malin de L’Aube, then Count Malin de Gondreville, was a politician born in 1759 (see Ténébreuse affaire; Paix du ménage). Marries a Sibuelle, daughter of a rather disreputable supplier. They had a son, Charles, a soldier killed in 1823, who had a natural son by Madame Colleville; a daughter Cécile who married François Keller, a liberal deputy and later Count and Peer of France; and another daughter who married the Duc de Carigliano.

Character genealogy source: Félicien Marceau “Balzac et son monde” Gallimard.

No Comments