Foreword to The Human Comedy

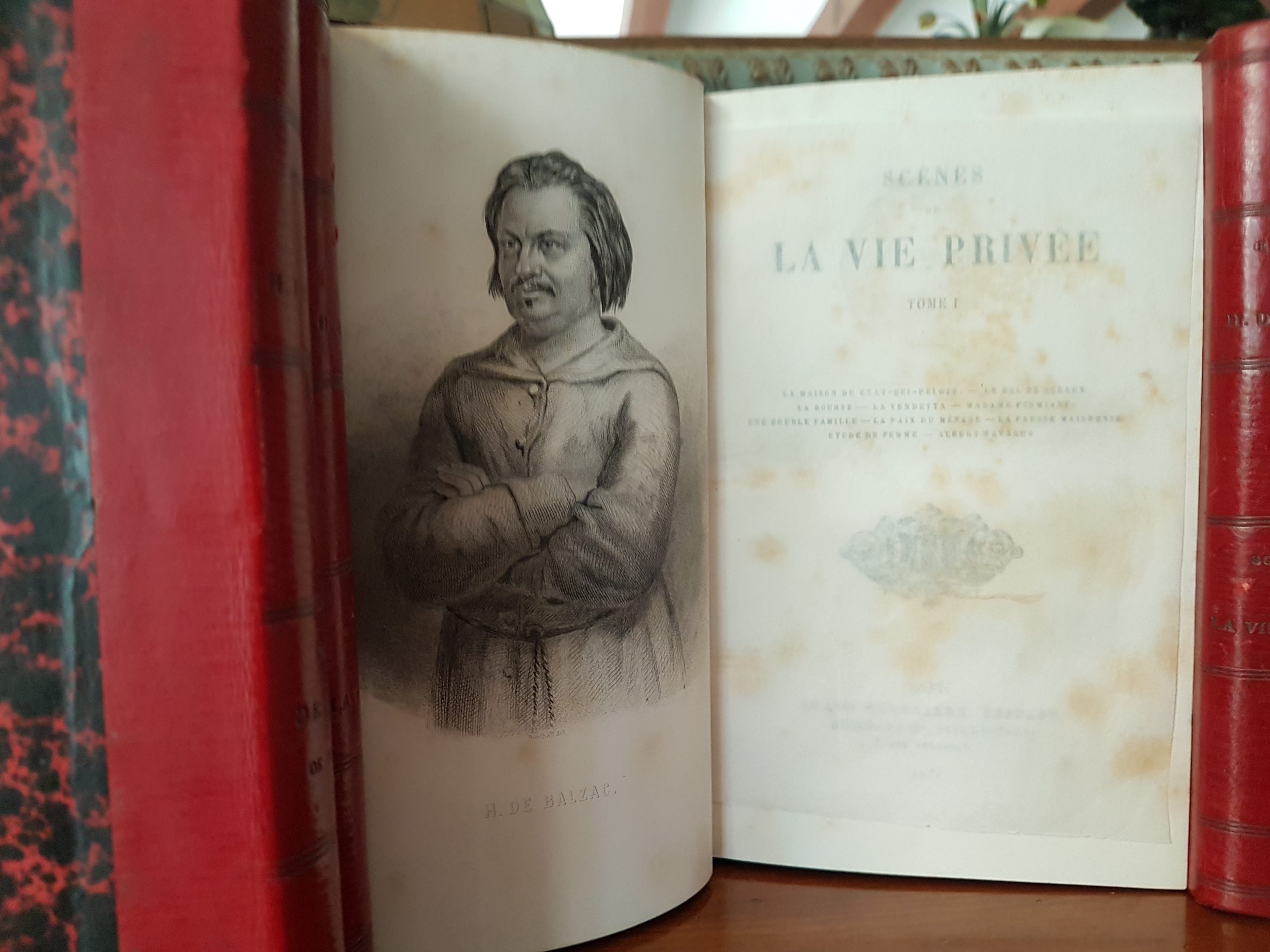

Foreword to The Human Comedy by Honoré de Balzac (1842)  In giving a work that has been in progress for nearly thirteen years the title of The Human Comedy, it is necessary to explain the thinking behind it, to tell its origin, to briefly explain its plan, trying to talk about these things as if I were not interested in them. This is not as difficult as the public might think. A little work gives a lot of self-esteem, a lot of work gives infinite modesty. This observation reflects the examinations that Corneille, Molière and other great authors made of their works: if it’s impossible to equal them in their beautiful conceptions, we can want to resemble them in this sentiment. The first idea for The Human Comedy was like a dream to me, like one of those impossible projects that you caress and let fly away; a chimera that smiles, shows its womanly face and immediately spreads its wings, soaring up into a fantastic sky. But the chimera, like many chimeras, changes into reality, it has its commands and its tyranny to which we must give in. This idea came from a comparison between Humanity and Animality. It would be a mistake to believe that the great quarrel that has recently flared up between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was based on a scientific innovation. Theunity of composition had already occupied the greatest minds of the previous two centuries under other terms. If we reread the extraordinary works of mystical writers concerned with the sciences in their relationship with the infinite, such as Swedenborg, Saint-Martin, etc., and the writings of the finest geniuses in natural history, such as Leibnitz, Buffon, Charles Bonnet, etc., we find in Leibnitz’s monads, in Buffon’s organic molecules, in Needham’s vegetative force, in theThe interlocking of similar parts by Charles Bonnet, bold enough to write in 1760: L’animal végète comme la plante; we find, I say, the rudiments of the beautiful law of self for self on which theunity of composition rests. There’s only one animal. The Creator used a single pattern for all organized beings. The animal is a principle that takes its external form, or, to put it more accurately, the differences in its form, in the environments where it is called upon to develop. Zoological species are the result of these differences. The proclamation and support of this system, in harmony with the ideas we have of divine power, will be a key factor in our success.

In giving a work that has been in progress for nearly thirteen years the title of The Human Comedy, it is necessary to explain the thinking behind it, to tell its origin, to briefly explain its plan, trying to talk about these things as if I were not interested in them. This is not as difficult as the public might think. A little work gives a lot of self-esteem, a lot of work gives infinite modesty. This observation reflects the examinations that Corneille, Molière and other great authors made of their works: if it’s impossible to equal them in their beautiful conceptions, we can want to resemble them in this sentiment. The first idea for The Human Comedy was like a dream to me, like one of those impossible projects that you caress and let fly away; a chimera that smiles, shows its womanly face and immediately spreads its wings, soaring up into a fantastic sky. But the chimera, like many chimeras, changes into reality, it has its commands and its tyranny to which we must give in. This idea came from a comparison between Humanity and Animality. It would be a mistake to believe that the great quarrel that has recently flared up between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was based on a scientific innovation. Theunity of composition had already occupied the greatest minds of the previous two centuries under other terms. If we reread the extraordinary works of mystical writers concerned with the sciences in their relationship with the infinite, such as Swedenborg, Saint-Martin, etc., and the writings of the finest geniuses in natural history, such as Leibnitz, Buffon, Charles Bonnet, etc., we find in Leibnitz’s monads, in Buffon’s organic molecules, in Needham’s vegetative force, in theThe interlocking of similar parts by Charles Bonnet, bold enough to write in 1760: L’animal végète comme la plante; we find, I say, the rudiments of the beautiful law of self for self on which theunity of composition rests. There’s only one animal. The Creator used a single pattern for all organized beings. The animal is a principle that takes its external form, or, to put it more accurately, the differences in its form, in the environments where it is called upon to develop. Zoological species are the result of these differences. The proclamation and support of this system, in harmony with the ideas we have of divine power, will be a key factor in our success.  the eternal honor of Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Cuvier’s conqueror on this point of high science, and whose triumph was hailed by the last article written by the great Goethe. I was convinced of this system long before the debates to which it gave rise, and I saw that, in this respect, the Company resembled Nature. Doesn’t society make man, according to the environments in which his action takes place, as many different men as there are varieties in zoology? The differences between a soldier, a worker, an administrator, a lawyer, an idler, a scholar, a statesman, a merchant, a sailor, a poet, a pauper, a priest, are, although more difficult to grasp, as considerable as those which distinguish the wolf, the lion, the donkey, the crow, the shark, the sea calf, the sheep, etc. Social species have always existed and will always exist, just as there are zoological species. If Buffon produced a magnificent work by attempting to represent the whole of zoology in one book, wasn’t there a similar work to be done for the Society? But Nature has set limits for animal varieties, between which the Company must not stand. When Buffon painted the lion, he completed the lioness in just a few sentences; whereas in Society, the female is not always the male’s female. There can be two perfectly dissimilar people in a household. A merchant’s wife is sometimes worthy of a prince’s, and a prince’s wife is often not worth an artist’s wife. The Social State has hazards that Nature does not allow itself, for it is Nature plus Society. The description of Social Species was therefore at least double that of Animal Species, considering only the two sexes. Finally, there’s little drama between the animals, and confusion is hardly ever an issue; they just run at each other, that’s all. Men also run at each other, but their varying degrees of intelligence make the battle more complicated. If some scientists don’t yet admit that Animality is transposed into Humanity by an immense current of life, the grocer certainly becomes a peer of France, and the nobleman sometimes descends to the lowest social rank. Then, Buffon found life excessively simple in animals. The animal has little furniture, no arts or sciences; whereas man, by a law to be sought, tends to represent his morals, his thought and his life in everything he appropriates to his needs. Although Leuwenhoëk, Swammerdam, Spallanzani, Réaumur, Charles Bonnet, Muller, Haller and other patient zoographers have demonstrated how interesting animal mores are, the habits of each animal are, to our eyes at least, constantly similar at all times ; whereas the habits, clothes, words and homes of a prince, a banker, an artist, a bourgeois, a priest and a pauper are entirely dissimilar, and change with civilization. So the work to be done had to have a triple form: men, women and things, i.e. people and the material representation they give of their thoughts; finally, man and life. Reading the dry, off-putting nomenclatures of facts called histories, who hasn’t noticed that writers have forgotten, in all ages, in Egypt, Persia, Greece, Rome, to give us the history of morals. Petronius’ piece on the private lives of the Romans irritates rather than satisfies our curiosity. After noticing this huge gap in the field of history, Abbé Barthélemy devoted his life to remaking Greek mores in Anacharsis.

the eternal honor of Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Cuvier’s conqueror on this point of high science, and whose triumph was hailed by the last article written by the great Goethe. I was convinced of this system long before the debates to which it gave rise, and I saw that, in this respect, the Company resembled Nature. Doesn’t society make man, according to the environments in which his action takes place, as many different men as there are varieties in zoology? The differences between a soldier, a worker, an administrator, a lawyer, an idler, a scholar, a statesman, a merchant, a sailor, a poet, a pauper, a priest, are, although more difficult to grasp, as considerable as those which distinguish the wolf, the lion, the donkey, the crow, the shark, the sea calf, the sheep, etc. Social species have always existed and will always exist, just as there are zoological species. If Buffon produced a magnificent work by attempting to represent the whole of zoology in one book, wasn’t there a similar work to be done for the Society? But Nature has set limits for animal varieties, between which the Company must not stand. When Buffon painted the lion, he completed the lioness in just a few sentences; whereas in Society, the female is not always the male’s female. There can be two perfectly dissimilar people in a household. A merchant’s wife is sometimes worthy of a prince’s, and a prince’s wife is often not worth an artist’s wife. The Social State has hazards that Nature does not allow itself, for it is Nature plus Society. The description of Social Species was therefore at least double that of Animal Species, considering only the two sexes. Finally, there’s little drama between the animals, and confusion is hardly ever an issue; they just run at each other, that’s all. Men also run at each other, but their varying degrees of intelligence make the battle more complicated. If some scientists don’t yet admit that Animality is transposed into Humanity by an immense current of life, the grocer certainly becomes a peer of France, and the nobleman sometimes descends to the lowest social rank. Then, Buffon found life excessively simple in animals. The animal has little furniture, no arts or sciences; whereas man, by a law to be sought, tends to represent his morals, his thought and his life in everything he appropriates to his needs. Although Leuwenhoëk, Swammerdam, Spallanzani, Réaumur, Charles Bonnet, Muller, Haller and other patient zoographers have demonstrated how interesting animal mores are, the habits of each animal are, to our eyes at least, constantly similar at all times ; whereas the habits, clothes, words and homes of a prince, a banker, an artist, a bourgeois, a priest and a pauper are entirely dissimilar, and change with civilization. So the work to be done had to have a triple form: men, women and things, i.e. people and the material representation they give of their thoughts; finally, man and life. Reading the dry, off-putting nomenclatures of facts called histories, who hasn’t noticed that writers have forgotten, in all ages, in Egypt, Persia, Greece, Rome, to give us the history of morals. Petronius’ piece on the private lives of the Romans irritates rather than satisfies our curiosity. After noticing this huge gap in the field of history, Abbé Barthélemy devoted his life to remaking Greek mores in Anacharsis.  But how to make the three- or four-thousand-character drama presented by a Company interesting? how to please the poet, the philosopher and the masses who want poetry and philosophy in striking images? While I could see the importance and poetry of this story of the human heart, I could see no way of executing it; for, up to our time, the most famous storytellers had spent their talent creating one or two typical characters, painting one face of life. It was with this in mind that I read Walter Scott’s works. Walter Scott, that modern trouverur, was giving a gigantic allure to a genre of composition unjustly called secondary. Isn’t it really more difficult to compete with the Etat-Civil with Daphnis et Chloë, Roland, Amadis, Panurge, Don Quichotte, Manon Lescaut, Clarisse, Lovelace, Robinson Crusoe, Gilblas, Ossian, Julie d’Etanges, mon oncle Tobie, Werther, René, Corinne, Adolphe, Paul et Virginie, Jeanie Dean, Claverhouse, Ivanhoë, Manfred, Mignon, than to put in order facts that are more or less the same in all nations, to search for the spirit of laws that have fallen into disuse, to write theories that lead people astray, or, like some metaphysicians, to explain what is? First of all, these characters, whose existence becomes longer and more authentic than that of the generations in whose midst they are born, almost always live only on the condition of being a great image of the present. Conceived in the bowels of their century, the whole human heart is stirred beneath their envelope, often concealing an entire philosophy. Walter Scott thus elevated the novel to the philosophical value of history, that literature which, from century to century, inlays immortal diamonds on the poetic crown of countries where letters are cultivated. He brought together drama, dialogue, portraiture, landscape and description; he brought in the marvellous and the true, those elements of epic, and he brought poetry alongside the familiarity of the humblest languages. But, having not so much devised a system as found his way in the heat of work or by the logic of that work, he had not thought of linking his compositions together in such a way as to coordinate a complete story, each chapter of which would have been a novel, and each novel an era. When I noticed this lack of connection, which by the way does not make the Scotsman any less great, I saw both the system favorable to the execution of my work and the possibility of executing it. Although, so to speak, dazzled by Walter Scott’s surprising fecundity, always similar to himself and always original, I was not despairing, for I found the reason for this talent in the infinite variety of human nature. Chance is the world’s greatest novelist: to be fruitful, all you have to do is study it. The French Society was to be the historian, and I was only to be the secretary. By drawing up an inventory of vices and virtues, by gathering together the main facts of passions, by painting characters, by choosing the main events of society, by composing types by bringing together the traits of several homogeneous characters, perhaps I could manage to write the history forgotten by so many historians, that of morals. With a great deal of patience and courage, I would produce a book on France in the 19th century that we all regret, that Rome, Athens, Tyre, Memphis, Persia and India have unfortunately not left us on their civilizations, and that, following the example of Abbé Barthélemy, the courageous and patient Monteil had tried for the Middle Ages, but in an unattractive form. This work was nothing yet. Sticking to this rigorous reproduction, a writer could become a more or less faithful, more or less happy, patient or courageous painter of human types, the storyteller of the dramas of intimate life, the archaeologist of social furniture, the nomenclator of professions, the recorder of good and evil; but, to deserve the praise that every artist must aspire to, didn’t I have to study the reasons or rationale behind these social effects, to surprise the hidden meaning in this immense assemblage of figures, passions and events. Finally, having sought – I don’t mean found – this reason, this social driving force, shouldn’t we meditate on natural principles and see how Societies deviate from or approach the eternal rule, the true, the beautiful? Despite the scope of the premises, which could be a work in themselves, the work, to be complete, needed a conclusion. Thus depicted, the Society had to carry with it the reason for its movement. The law of the writer, what makes him such, I’m not afraid to say, makes him equal and perhaps superior to the statesman, is a decision of some sort on human things, an absolute devotion to principles. Machiavelli, Hobbes, Bossuet, Leibnitz, Kant, Montesquieu are the science that

But how to make the three- or four-thousand-character drama presented by a Company interesting? how to please the poet, the philosopher and the masses who want poetry and philosophy in striking images? While I could see the importance and poetry of this story of the human heart, I could see no way of executing it; for, up to our time, the most famous storytellers had spent their talent creating one or two typical characters, painting one face of life. It was with this in mind that I read Walter Scott’s works. Walter Scott, that modern trouverur, was giving a gigantic allure to a genre of composition unjustly called secondary. Isn’t it really more difficult to compete with the Etat-Civil with Daphnis et Chloë, Roland, Amadis, Panurge, Don Quichotte, Manon Lescaut, Clarisse, Lovelace, Robinson Crusoe, Gilblas, Ossian, Julie d’Etanges, mon oncle Tobie, Werther, René, Corinne, Adolphe, Paul et Virginie, Jeanie Dean, Claverhouse, Ivanhoë, Manfred, Mignon, than to put in order facts that are more or less the same in all nations, to search for the spirit of laws that have fallen into disuse, to write theories that lead people astray, or, like some metaphysicians, to explain what is? First of all, these characters, whose existence becomes longer and more authentic than that of the generations in whose midst they are born, almost always live only on the condition of being a great image of the present. Conceived in the bowels of their century, the whole human heart is stirred beneath their envelope, often concealing an entire philosophy. Walter Scott thus elevated the novel to the philosophical value of history, that literature which, from century to century, inlays immortal diamonds on the poetic crown of countries where letters are cultivated. He brought together drama, dialogue, portraiture, landscape and description; he brought in the marvellous and the true, those elements of epic, and he brought poetry alongside the familiarity of the humblest languages. But, having not so much devised a system as found his way in the heat of work or by the logic of that work, he had not thought of linking his compositions together in such a way as to coordinate a complete story, each chapter of which would have been a novel, and each novel an era. When I noticed this lack of connection, which by the way does not make the Scotsman any less great, I saw both the system favorable to the execution of my work and the possibility of executing it. Although, so to speak, dazzled by Walter Scott’s surprising fecundity, always similar to himself and always original, I was not despairing, for I found the reason for this talent in the infinite variety of human nature. Chance is the world’s greatest novelist: to be fruitful, all you have to do is study it. The French Society was to be the historian, and I was only to be the secretary. By drawing up an inventory of vices and virtues, by gathering together the main facts of passions, by painting characters, by choosing the main events of society, by composing types by bringing together the traits of several homogeneous characters, perhaps I could manage to write the history forgotten by so many historians, that of morals. With a great deal of patience and courage, I would produce a book on France in the 19th century that we all regret, that Rome, Athens, Tyre, Memphis, Persia and India have unfortunately not left us on their civilizations, and that, following the example of Abbé Barthélemy, the courageous and patient Monteil had tried for the Middle Ages, but in an unattractive form. This work was nothing yet. Sticking to this rigorous reproduction, a writer could become a more or less faithful, more or less happy, patient or courageous painter of human types, the storyteller of the dramas of intimate life, the archaeologist of social furniture, the nomenclator of professions, the recorder of good and evil; but, to deserve the praise that every artist must aspire to, didn’t I have to study the reasons or rationale behind these social effects, to surprise the hidden meaning in this immense assemblage of figures, passions and events. Finally, having sought – I don’t mean found – this reason, this social driving force, shouldn’t we meditate on natural principles and see how Societies deviate from or approach the eternal rule, the true, the beautiful? Despite the scope of the premises, which could be a work in themselves, the work, to be complete, needed a conclusion. Thus depicted, the Society had to carry with it the reason for its movement. The law of the writer, what makes him such, I’m not afraid to say, makes him equal and perhaps superior to the statesman, is a decision of some sort on human things, an absolute devotion to principles. Machiavelli, Hobbes, Bossuet, Leibnitz, Kant, Montesquieu are the science that  statesmen apply. “A writer must have firm opinions on morality and politics, and must see himself as a teacher of men; for men don’t need teachers to doubt,” said Bonald. Early on, I made a rule of these great words, which are the law of the monarchical as well as the democratic writer. So, when someone wants to pit me against myself, they may misinterpret some irony, or misjudge the speech of one of my characters, a maneuver peculiar to slanderers. As for the inner meaning and age of this work, here are the principles on which it is based. Man is neither good nor bad; he is born with instincts and aptitudes; society, far from depraving him, as Rousseau claimed, perfects him, makes him better; but interest also develops his evil inclinations. Christianity, and especially Catholicism, being, as I said in The Country Doctor, a complete system of repression of man’s depraved tendencies, is the greatest element of Social Order. A careful reading of the picture of society, molded, as it were, from life, with all its good and all its evil, teaches us that if thought, or passion, which includes thought and feeling, is the social element, it is also its destructive element. In this, social life resembles human life. You can only give people longevity by moderating their vital action. Teaching, or better, education by Religious Bodies is therefore the great principle of existence for peoples, the only way to diminish the sum of evil and increase the sum of good in any Society. Thought, the principle of both good and evil, can only be prepared, tamed and directed by religion. The only possible religion is Christianity (see Louis Lambert ‘s letter from Paris, in which the young mystic-philosopher explains, with reference to Swedenborg’s doctrine, how there has only ever been one religion since the beginning of the world). Christianity created modern peoples, and it will preserve them. Hence, no doubt, the need for the monarchical principle. Catholicism and Royalty are twin principles. As for the limits within which these two principles must be confined by Institutions so as not to let them develop absolutely, everyone will feel that a preface as succinct as this one must be cannot become a political treatise. So I mustn’t get involved in the religious or political dissensions of the moment. I write in the light of two eternal Truths: Religion, Monarchy, two necessities that contemporary events proclaim, and towards which every writer of good sense must try to lead our country back. Without being the enemy of Election, an excellent principle for constituting the law, I repudiate Election taken as the sole social means, and especially as badly organized as it is today, because it does not represent imposing minorities whose ideas and interests a monarchical government would consider. Election, extended to everything, gives us government by the masses, the only form of government that is not accountable, and where tyranny knows no bounds, for it is called law. That’s why I see the Family, and not the individual, as the true social element. In this respect, at the risk of being seen as backward-looking, I side with Bossuet and Bonald,

statesmen apply. “A writer must have firm opinions on morality and politics, and must see himself as a teacher of men; for men don’t need teachers to doubt,” said Bonald. Early on, I made a rule of these great words, which are the law of the monarchical as well as the democratic writer. So, when someone wants to pit me against myself, they may misinterpret some irony, or misjudge the speech of one of my characters, a maneuver peculiar to slanderers. As for the inner meaning and age of this work, here are the principles on which it is based. Man is neither good nor bad; he is born with instincts and aptitudes; society, far from depraving him, as Rousseau claimed, perfects him, makes him better; but interest also develops his evil inclinations. Christianity, and especially Catholicism, being, as I said in The Country Doctor, a complete system of repression of man’s depraved tendencies, is the greatest element of Social Order. A careful reading of the picture of society, molded, as it were, from life, with all its good and all its evil, teaches us that if thought, or passion, which includes thought and feeling, is the social element, it is also its destructive element. In this, social life resembles human life. You can only give people longevity by moderating their vital action. Teaching, or better, education by Religious Bodies is therefore the great principle of existence for peoples, the only way to diminish the sum of evil and increase the sum of good in any Society. Thought, the principle of both good and evil, can only be prepared, tamed and directed by religion. The only possible religion is Christianity (see Louis Lambert ‘s letter from Paris, in which the young mystic-philosopher explains, with reference to Swedenborg’s doctrine, how there has only ever been one religion since the beginning of the world). Christianity created modern peoples, and it will preserve them. Hence, no doubt, the need for the monarchical principle. Catholicism and Royalty are twin principles. As for the limits within which these two principles must be confined by Institutions so as not to let them develop absolutely, everyone will feel that a preface as succinct as this one must be cannot become a political treatise. So I mustn’t get involved in the religious or political dissensions of the moment. I write in the light of two eternal Truths: Religion, Monarchy, two necessities that contemporary events proclaim, and towards which every writer of good sense must try to lead our country back. Without being the enemy of Election, an excellent principle for constituting the law, I repudiate Election taken as the sole social means, and especially as badly organized as it is today, because it does not represent imposing minorities whose ideas and interests a monarchical government would consider. Election, extended to everything, gives us government by the masses, the only form of government that is not accountable, and where tyranny knows no bounds, for it is called law. That’s why I see the Family, and not the individual, as the true social element. In this respect, at the risk of being seen as backward-looking, I side with Bossuet and Bonald,  instead of going with the modern innovators. As Election has become the only social means, if I were to resort to it for myself, I wouldn’t have to infer the slightest contradiction between my actions and my thinking. An engineer announces that such and such a bridge is close to collapse, that it is dangerous for everyone to use it, and he goes over it himself when this bridge is the only route to the city. Napoleon had wonderfully adapted the Election to the genius of our country. As a result, the smallest members of the Corps Législatif were the most famous orators in the Chambers during the Restoration. No Chamber has matched the Corps Législatif by comparing them man for man. The Empire’s elective system is undeniably the best. Some people may find something superb and advantageous in this statement. People will quarrel with the novelist because he wants to be a historian, and ask him to explain his politics. I’m obeying an obligation here, that’s the whole answer. The work I have undertaken will have the length of a history, and I had to give the reason, still hidden, the principles and the moral. Necessarily forced to delete the prefaces published in response to what are essentially passing criticisms, I only wish to retain one observation. Writers who have a goal, even if it’s a return to the principles of the past because they are eternal, must always clear the way. Now, anyone who makes a contribution in the field of ideas, anyone who points out an abuse, anyone who marks the bad to be cut off, always passes for immoral. The reproach of immorality, which has never failed the courageous writer, is in fact the last to be made when you have nothing more to say to a poet. If your paintings are true to life, if by dint of day and night work you manage to write the most difficult language in the world, then the word immoral is thrown in your face. Socrates was immoral, Jesus Christ was immoral; both were prosecuted in the name of the societies they overthrew or reformed. When you want to kill someone, you accuse them of immorality. This maneuver, familiar to all parties, is a disgrace to all who employ it. Luther and Calvin knew what they were doing when they used wounded material interests as a shield! So they lived their whole lives. In copying the whole Society, capturing it in the immensity of its turmoil, it happens, it was bound to happen that such and such a composition offered more evil than good, that such and such a part of the fresco represented a guilty group, and the critics cried immorality, without pointing out the morality of such and such another part intended to form a perfect contrast. As the critic was unaware of the general plan, I forgave him all the more because criticism can no more be prevented than sight, language and judgment can be prevented. But the time for impartiality has not yet come for me. Moreover, an author who cannot bring himself to face the fire of criticism should no more set out to write than a traveller should set out to travel, counting on a sky that is always serene. On this point, it remains for me to point out that the most conscientious moralists doubt very much that Society can offer as many good deeds as bad, and in the picture I paint of it, there are more virtuous characters than reprehensible ones. Reprehensible actions, faults and crimes, from the mildest to the most serious, always find their human or divine punishment, overt or covert. I’ve done better

instead of going with the modern innovators. As Election has become the only social means, if I were to resort to it for myself, I wouldn’t have to infer the slightest contradiction between my actions and my thinking. An engineer announces that such and such a bridge is close to collapse, that it is dangerous for everyone to use it, and he goes over it himself when this bridge is the only route to the city. Napoleon had wonderfully adapted the Election to the genius of our country. As a result, the smallest members of the Corps Législatif were the most famous orators in the Chambers during the Restoration. No Chamber has matched the Corps Législatif by comparing them man for man. The Empire’s elective system is undeniably the best. Some people may find something superb and advantageous in this statement. People will quarrel with the novelist because he wants to be a historian, and ask him to explain his politics. I’m obeying an obligation here, that’s the whole answer. The work I have undertaken will have the length of a history, and I had to give the reason, still hidden, the principles and the moral. Necessarily forced to delete the prefaces published in response to what are essentially passing criticisms, I only wish to retain one observation. Writers who have a goal, even if it’s a return to the principles of the past because they are eternal, must always clear the way. Now, anyone who makes a contribution in the field of ideas, anyone who points out an abuse, anyone who marks the bad to be cut off, always passes for immoral. The reproach of immorality, which has never failed the courageous writer, is in fact the last to be made when you have nothing more to say to a poet. If your paintings are true to life, if by dint of day and night work you manage to write the most difficult language in the world, then the word immoral is thrown in your face. Socrates was immoral, Jesus Christ was immoral; both were prosecuted in the name of the societies they overthrew or reformed. When you want to kill someone, you accuse them of immorality. This maneuver, familiar to all parties, is a disgrace to all who employ it. Luther and Calvin knew what they were doing when they used wounded material interests as a shield! So they lived their whole lives. In copying the whole Society, capturing it in the immensity of its turmoil, it happens, it was bound to happen that such and such a composition offered more evil than good, that such and such a part of the fresco represented a guilty group, and the critics cried immorality, without pointing out the morality of such and such another part intended to form a perfect contrast. As the critic was unaware of the general plan, I forgave him all the more because criticism can no more be prevented than sight, language and judgment can be prevented. But the time for impartiality has not yet come for me. Moreover, an author who cannot bring himself to face the fire of criticism should no more set out to write than a traveller should set out to travel, counting on a sky that is always serene. On this point, it remains for me to point out that the most conscientious moralists doubt very much that Society can offer as many good deeds as bad, and in the picture I paint of it, there are more virtuous characters than reprehensible ones. Reprehensible actions, faults and crimes, from the mildest to the most serious, always find their human or divine punishment, overt or covert. I’ve done better  I’m freer than the historian. Here on earth, Cromwell had no punishment other than that inflicted on him by the thinker. Again, this was a school-to-school discussion. Bossuet himself spared this great regicide. William of Orange, the usurper, and Hugues Capet, that other usurper, died full of days, without having had more doubts or more fears than Henri IV and Charles I. If we were to compare the lives of Catherine II and Louis XVI, we would conclude against any kind of morality, judging them from the point of view of the morality that governs private individuals; for kings, for statesmen, there is, as Napoleon said, a small and a large morality. Scenes from Political Life is based on this beautiful reflection. The law of history, like the novel, is not to strive for the ideal of beauty. History is, or ought to be, what it was; while the novel must be the better world, said Mme Necker, one of the most distinguished minds of the last century. But the novel would be nothing if, in this august lie, it were not true in detail. Forced to conform to the ideas of an essentially hypocritical country, Walter Scott was wrong, in relation to humanity, in his painting of women, because his models were schismatics. Protestant women have no ideal. She may be chaste, pure, virtuous; but her love without expansion will always be calm and tidy, like a duty fulfilled. It would seem that the Virgin Mary has cooled the hearts of the sophists who banished her and her treasures of mercy from heaven. In Protestantism, nothing is possible for the woman after the sin, whereas in the Catholic Church, the hope of forgiveness makes her sublime. So there’s only one woman for the Protestant writer, while the Catholic writer finds a new woman in every new situation. If Walter Scott had been a Catholic, if he had set himself the task of truly describing the different Societies that have succeeded one another in Scotland, perhaps the painter of Effie and Alice (the two figures he reproached himself in his old age for having drawn) would have admitted the passions with their faults and their punishments, with the virtues that repentance indicates to them. Passion is all humanity. Without it, religion, history, novels and art would be useless. Seeing me amass so many facts and painting them as they are, with passion as my element, some people imagined, quite wrongly, that I belonged to the sensualist and materialist school, two sides of the same fact, pantheism. But perhaps we could have been, or should have been, mistaken. I don’t share the belief in indefinite progress as far as companies are concerned, but I do believe in man’s progress in relation to himself. Those who want to see in me the intention of considering man as a finite creature are therefore strangely mistaken. Seraphita, the doctrine in action of the Christian Buddha, seems to me a sufficient response to this accusation, which is, incidentally, rather lightly advanced. In certain parts of this long work, I’ve tried to popularize the astonishing facts, I might say the prodigies, of electricity, which metamorphoses in man into incalculable power; but how do the cerebral and nervous phenomena that demonstrate the existence of a new moral world disturb the certain and necessary relationships between the worlds and God? in what way would Catholic dogmas be undermined?

I’m freer than the historian. Here on earth, Cromwell had no punishment other than that inflicted on him by the thinker. Again, this was a school-to-school discussion. Bossuet himself spared this great regicide. William of Orange, the usurper, and Hugues Capet, that other usurper, died full of days, without having had more doubts or more fears than Henri IV and Charles I. If we were to compare the lives of Catherine II and Louis XVI, we would conclude against any kind of morality, judging them from the point of view of the morality that governs private individuals; for kings, for statesmen, there is, as Napoleon said, a small and a large morality. Scenes from Political Life is based on this beautiful reflection. The law of history, like the novel, is not to strive for the ideal of beauty. History is, or ought to be, what it was; while the novel must be the better world, said Mme Necker, one of the most distinguished minds of the last century. But the novel would be nothing if, in this august lie, it were not true in detail. Forced to conform to the ideas of an essentially hypocritical country, Walter Scott was wrong, in relation to humanity, in his painting of women, because his models were schismatics. Protestant women have no ideal. She may be chaste, pure, virtuous; but her love without expansion will always be calm and tidy, like a duty fulfilled. It would seem that the Virgin Mary has cooled the hearts of the sophists who banished her and her treasures of mercy from heaven. In Protestantism, nothing is possible for the woman after the sin, whereas in the Catholic Church, the hope of forgiveness makes her sublime. So there’s only one woman for the Protestant writer, while the Catholic writer finds a new woman in every new situation. If Walter Scott had been a Catholic, if he had set himself the task of truly describing the different Societies that have succeeded one another in Scotland, perhaps the painter of Effie and Alice (the two figures he reproached himself in his old age for having drawn) would have admitted the passions with their faults and their punishments, with the virtues that repentance indicates to them. Passion is all humanity. Without it, religion, history, novels and art would be useless. Seeing me amass so many facts and painting them as they are, with passion as my element, some people imagined, quite wrongly, that I belonged to the sensualist and materialist school, two sides of the same fact, pantheism. But perhaps we could have been, or should have been, mistaken. I don’t share the belief in indefinite progress as far as companies are concerned, but I do believe in man’s progress in relation to himself. Those who want to see in me the intention of considering man as a finite creature are therefore strangely mistaken. Seraphita, the doctrine in action of the Christian Buddha, seems to me a sufficient response to this accusation, which is, incidentally, rather lightly advanced. In certain parts of this long work, I’ve tried to popularize the astonishing facts, I might say the prodigies, of electricity, which metamorphoses in man into incalculable power; but how do the cerebral and nervous phenomena that demonstrate the existence of a new moral world disturb the certain and necessary relationships between the worlds and God? in what way would Catholic dogmas be undermined?  If, by indisputable facts, thought is one day classed among the fluids that are revealed only by their effects, and whose substance escapes our senses even when enlarged by so many mechanical means, it will be as with the sphericity of the earth observed by Christopher Columbus, as with its rotation demonstrated by Galileo. Our future will remain the same. Animal magnetism, the miracles of which I’ve been familiar with since 1820; the fine research of Gall, Lavater’s successor; all those who, for fifty years, have worked on thought as opticians have worked on light, two things that are almost the same, conclude both the mystics, those disciples of the apostle Saint John, and all the great thinkers who have established the spiritual world, that sphere where the relationship between man and God is revealed. If you fully grasp the meaning of this composition, you will recognize that I attach as much importance to constant, daily, secret or obvious facts, to acts of individual life, to their causes and principles, as historians have hitherto attached to events in the public life of nations. The unknown battle fought between Madame de Mortsauf and passion in a valley of the Indre is perhaps as great as the most famous of all known battles(Le Lys dans la vallée). In one, the glory of a conqueror is at stake; in the other, heaven is at stake. For me, the misfortunes of the Birotteaus, the priest and the perfumer, are the misfortunes of humanity. La Fosseuse(country doctor) and Madame Graslin(village priest) are almost all women. We suffer like this every day. I’ve had to do a hundred times what Richardson only did once. Lovelace has a thousand forms, as social corruption takes on the colors of all the environments in which it develops. On the contrary, Clarisse, that beautiful image of passionate virtue, has lines of despairing purity. To create many virgins, you have to be Raphael. In this respect, literature is perhaps below painting. So may I point out how many irreproachable figures (as virtue) are to be found in the published portions of this work: Pierrette Lorrain, Ursule Mirouët, Constance Birotteau, la Fosseuse, Eugénie Grandet, Marguerite Claës, Pauline de Villenoix, madame Jules, madame de La Chanterie, Eve Chardon, mademoiselle d’Esgrignon, madame Firmiani, Agathe Rouget, Renée de Maucombe; in short, many figures in the background, who, though less prominent than these, nonetheless offer the reader the practice of domestic virtues. Joseph Lebas, Genestas, Benassis, le curé Bonnet, le médecin Minoret, Pillerault, David Séchard, the two Birotteaus, le curé Chaperon, le juge Popinot, Bourgeat, the Sauviat family, the Tascheron family, and many others, don’t they solve the difficult literary problem of how to make a virtuous character interesting. It was no small task to paint the two or three thousand outstanding figures of an era, for such is, in the final analysis, the sum of the types that each generation presents and that The Human Comedy will include. The sheer number of figures, characters and existences required frames and, if you’ll pardon the expression, galleries. Hence the natural divisions, already known, of my work into Scenes from private, provincial, Parisian, political, military and country life. These six books contain all the Etudes de moeurs which form the general history of the Company, the collection of all its deeds and gestures, as our ancestors would have said.

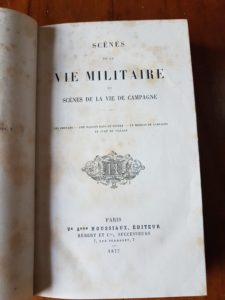

If, by indisputable facts, thought is one day classed among the fluids that are revealed only by their effects, and whose substance escapes our senses even when enlarged by so many mechanical means, it will be as with the sphericity of the earth observed by Christopher Columbus, as with its rotation demonstrated by Galileo. Our future will remain the same. Animal magnetism, the miracles of which I’ve been familiar with since 1820; the fine research of Gall, Lavater’s successor; all those who, for fifty years, have worked on thought as opticians have worked on light, two things that are almost the same, conclude both the mystics, those disciples of the apostle Saint John, and all the great thinkers who have established the spiritual world, that sphere where the relationship between man and God is revealed. If you fully grasp the meaning of this composition, you will recognize that I attach as much importance to constant, daily, secret or obvious facts, to acts of individual life, to their causes and principles, as historians have hitherto attached to events in the public life of nations. The unknown battle fought between Madame de Mortsauf and passion in a valley of the Indre is perhaps as great as the most famous of all known battles(Le Lys dans la vallée). In one, the glory of a conqueror is at stake; in the other, heaven is at stake. For me, the misfortunes of the Birotteaus, the priest and the perfumer, are the misfortunes of humanity. La Fosseuse(country doctor) and Madame Graslin(village priest) are almost all women. We suffer like this every day. I’ve had to do a hundred times what Richardson only did once. Lovelace has a thousand forms, as social corruption takes on the colors of all the environments in which it develops. On the contrary, Clarisse, that beautiful image of passionate virtue, has lines of despairing purity. To create many virgins, you have to be Raphael. In this respect, literature is perhaps below painting. So may I point out how many irreproachable figures (as virtue) are to be found in the published portions of this work: Pierrette Lorrain, Ursule Mirouët, Constance Birotteau, la Fosseuse, Eugénie Grandet, Marguerite Claës, Pauline de Villenoix, madame Jules, madame de La Chanterie, Eve Chardon, mademoiselle d’Esgrignon, madame Firmiani, Agathe Rouget, Renée de Maucombe; in short, many figures in the background, who, though less prominent than these, nonetheless offer the reader the practice of domestic virtues. Joseph Lebas, Genestas, Benassis, le curé Bonnet, le médecin Minoret, Pillerault, David Séchard, the two Birotteaus, le curé Chaperon, le juge Popinot, Bourgeat, the Sauviat family, the Tascheron family, and many others, don’t they solve the difficult literary problem of how to make a virtuous character interesting. It was no small task to paint the two or three thousand outstanding figures of an era, for such is, in the final analysis, the sum of the types that each generation presents and that The Human Comedy will include. The sheer number of figures, characters and existences required frames and, if you’ll pardon the expression, galleries. Hence the natural divisions, already known, of my work into Scenes from private, provincial, Parisian, political, military and country life. These six books contain all the Etudes de moeurs which form the general history of the Company, the collection of all its deeds and gestures, as our ancestors would have said.  All six books are based on general ideas. Each of them has its own meaning, its own significance, and formulates an epoch in human life. I’ll repeat here, albeit succinctly, what Félix Davin, a young talent taken from letters by an untimely death, wrote after inquiring about my plan. Scenes from Private Life represents childhood, adolescence and their faults, just as Scenes from Provincial Life represents the age of passions, calculations, interests and ambition. Scènes de la vie parisienne (Scenes of Parisian life ) depicts tastes, vices and all the unbridled things that excite the particular mores of capital cities, where both extreme good and extreme evil meet. Each of these three parts has its local color: Paris and the provinces, this social antithesis has provided its immense resources. Not only men, but also the main events of life, are formulated by types. There are situations that recur in every existence, typical phases, and this is one of the accuracies I’ve sought most. I’ve tried to give you an idea of the different regions of our beautiful country. My work has its geography as it has its genealogy and its families, its places and its things, its people and its facts; as it has its armorial, its nobles and its burghers, its craftsmen and its peasants, its politicians and its dandies, its army, its whole world at last! Having painted the picture of social life in these three books, it remained to show the exceptional existences that encapsulate the interests of several or all, which are in some way outside the common law: hence Scenes from Political Life. This vast painting of a finished and completed society, shouldn’t it have been shown in its most violent state, running away from home, either to defend or to conquer? Hence the Scènes de la vie militaire (Scenes from military life), the least complete part of my work, but which will be included in this edition, so that it will be part of it when I have finished it. Finally, Scènes de la vie de campagne is, in a way, the evening of this long day, if I may call the social drama that. In this book, we find the purest characters and the application of the great principles of order, politics and morality. Such is the foundation, full of figures, full of comedies and tragedies, on which the Philosophical studiesThe second part of the work, in which the social means of all effects is demonstrated, in which the ravages of thought are painted, feeling by feeling, and of which the first work, La Peau de chagrina kind of link between Etudes de moeurs at Philosophical studies by the ring of an almost oriental fantasy, in which Life itself is depicted grappling with Desire, the principle of all Passion. Above will be the Etudes analytiques, of which I will say nothing, as only one has been published, the Physiologie du mariage. In the near future, I’ll be giving away two more books of this kind. First came Pathologie de la vie sociale , thenAnatomie des corps enseignants and Monographie de la vertu. Seeing how much remains to be done, perhaps people will say of me what my publishers said: May God give you life! I only wish I wasn’t so tormented by men and by

All six books are based on general ideas. Each of them has its own meaning, its own significance, and formulates an epoch in human life. I’ll repeat here, albeit succinctly, what Félix Davin, a young talent taken from letters by an untimely death, wrote after inquiring about my plan. Scenes from Private Life represents childhood, adolescence and their faults, just as Scenes from Provincial Life represents the age of passions, calculations, interests and ambition. Scènes de la vie parisienne (Scenes of Parisian life ) depicts tastes, vices and all the unbridled things that excite the particular mores of capital cities, where both extreme good and extreme evil meet. Each of these three parts has its local color: Paris and the provinces, this social antithesis has provided its immense resources. Not only men, but also the main events of life, are formulated by types. There are situations that recur in every existence, typical phases, and this is one of the accuracies I’ve sought most. I’ve tried to give you an idea of the different regions of our beautiful country. My work has its geography as it has its genealogy and its families, its places and its things, its people and its facts; as it has its armorial, its nobles and its burghers, its craftsmen and its peasants, its politicians and its dandies, its army, its whole world at last! Having painted the picture of social life in these three books, it remained to show the exceptional existences that encapsulate the interests of several or all, which are in some way outside the common law: hence Scenes from Political Life. This vast painting of a finished and completed society, shouldn’t it have been shown in its most violent state, running away from home, either to defend or to conquer? Hence the Scènes de la vie militaire (Scenes from military life), the least complete part of my work, but which will be included in this edition, so that it will be part of it when I have finished it. Finally, Scènes de la vie de campagne is, in a way, the evening of this long day, if I may call the social drama that. In this book, we find the purest characters and the application of the great principles of order, politics and morality. Such is the foundation, full of figures, full of comedies and tragedies, on which the Philosophical studiesThe second part of the work, in which the social means of all effects is demonstrated, in which the ravages of thought are painted, feeling by feeling, and of which the first work, La Peau de chagrina kind of link between Etudes de moeurs at Philosophical studies by the ring of an almost oriental fantasy, in which Life itself is depicted grappling with Desire, the principle of all Passion. Above will be the Etudes analytiques, of which I will say nothing, as only one has been published, the Physiologie du mariage. In the near future, I’ll be giving away two more books of this kind. First came Pathologie de la vie sociale , thenAnatomie des corps enseignants and Monographie de la vertu. Seeing how much remains to be done, perhaps people will say of me what my publishers said: May God give you life! I only wish I wasn’t so tormented by men and by  things than I have since I undertook this appalling task. I had this for myself, for which I thank God, that the greatest talents of that time, that the finest characters, that sincere friends, as great in private life as these are in public life, shook my hand and said: “Courage! “And why shouldn’t I admit that these friendships, that testimonials given here and there by strangers, have sustained me in my career both against myself and against unjust attacks, against the slander that has so often pursued me, against discouragement and against that all-too-bright hope whose words are mistaken for those of excessive self-love? I had resolved to oppose attacks and insults with stoic impassivity; but, on two occasions, cowardly calumnies made defense necessary. While those in favor of forgiving insults regret that I have shown my knowledge of literary fencing, many Christians think that we live in a time when it is good to show that silence has generosity. In this regard, I must point out that I only recognize as my works those that bear my name. Apart from The Human Comedy, the only other works by me are the Cent contes drolatiques, two plays and a few isolated articles, all of which are signed. I’m exercising an undeniable right here. But this disavowal, even if it affects works in which I have collaborated, is prompted less by self-love than by truth. If someone persisted in attributing to me books which, literally speaking, I don’t recognize as my own, but whose ownership has been entrusted to me, I would let it be said, for the same reason that I leave the field open to slander. The immensity of a plan that embraces both the history and criticism of Society, the analysis of its evils and the discussion of its principles, authorizes me, I believe, to give my work the title under which it appears today: The Human Comedy. Is it ambitious? Isn’t that just? That’s what the public will decide when the work is finished.

things than I have since I undertook this appalling task. I had this for myself, for which I thank God, that the greatest talents of that time, that the finest characters, that sincere friends, as great in private life as these are in public life, shook my hand and said: “Courage! “And why shouldn’t I admit that these friendships, that testimonials given here and there by strangers, have sustained me in my career both against myself and against unjust attacks, against the slander that has so often pursued me, against discouragement and against that all-too-bright hope whose words are mistaken for those of excessive self-love? I had resolved to oppose attacks and insults with stoic impassivity; but, on two occasions, cowardly calumnies made defense necessary. While those in favor of forgiving insults regret that I have shown my knowledge of literary fencing, many Christians think that we live in a time when it is good to show that silence has generosity. In this regard, I must point out that I only recognize as my works those that bear my name. Apart from The Human Comedy, the only other works by me are the Cent contes drolatiques, two plays and a few isolated articles, all of which are signed. I’m exercising an undeniable right here. But this disavowal, even if it affects works in which I have collaborated, is prompted less by self-love than by truth. If someone persisted in attributing to me books which, literally speaking, I don’t recognize as my own, but whose ownership has been entrusted to me, I would let it be said, for the same reason that I leave the field open to slander. The immensity of a plan that embraces both the history and criticism of Society, the analysis of its evils and the discussion of its principles, authorizes me, I believe, to give my work the title under which it appears today: The Human Comedy. Is it ambitious? Isn’t that just? That’s what the public will decide when the work is finished.

Paris, July 1842.

No Comments